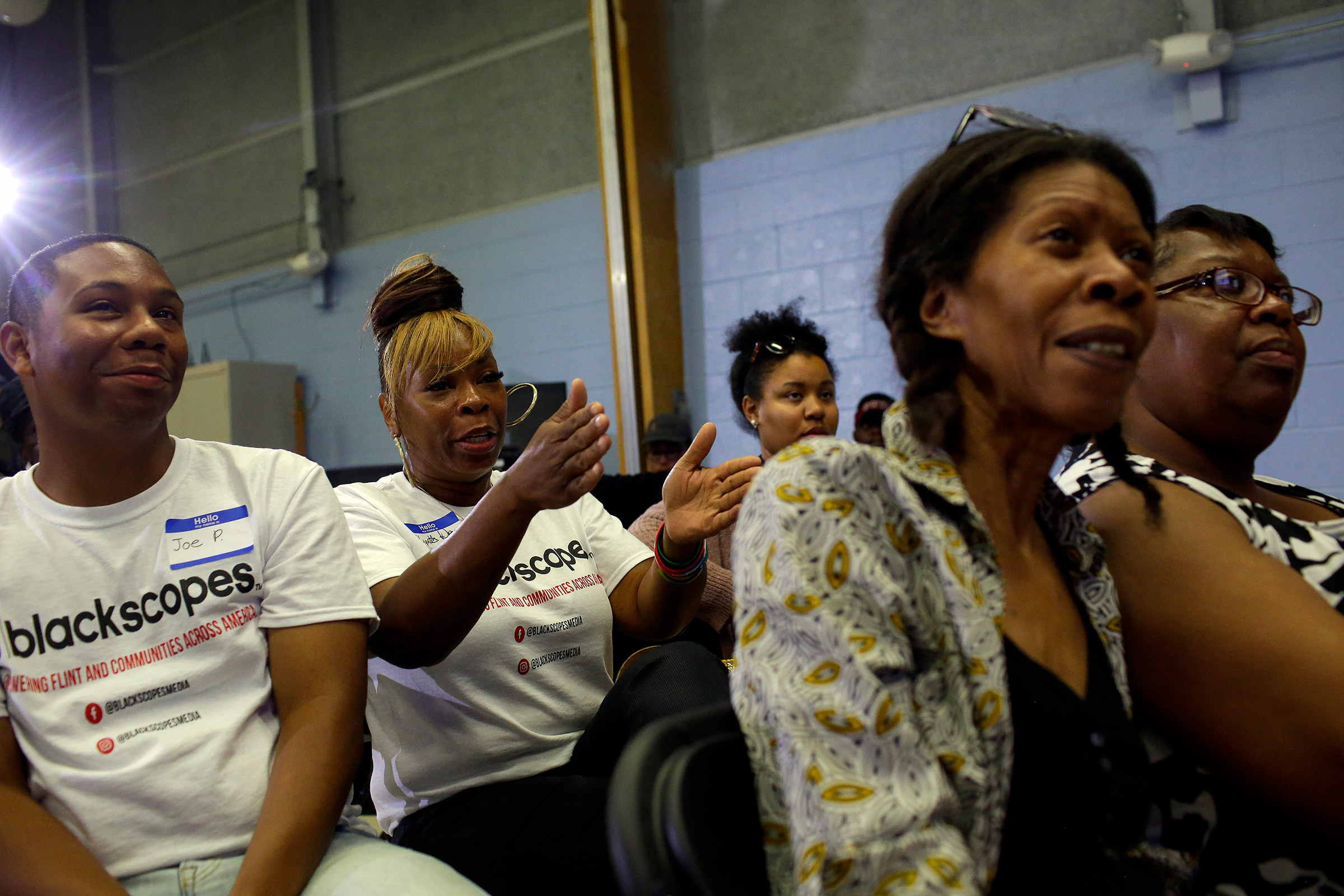

As the Democratic presidential candidates prepared to debate in Detroit Wednesday night, the dozen voters who gathered to watch in the cinderblock auditorium of the Flint Development Center some 70 miles away weren’t focused on the candidates or the polls. Nobody was talking about Senator Kamala Harris or former Vice President Joe Biden as they chatted over a meal of fried chicken and spaghetti provided by Black Voters Matter, the advocacy group that hosted the watch party. Instead, they talked about public school funding, an issue which barely came up on stage in Detroit. For 10 minutes after the debate’s scheduled 8 p.m. start time, the organizers didn’t even turn on the TV.

Black voters make up about 20% of the Democratic vote nationwide, and they are an increasingly critical component of the party’s electoral coalition. Because they often vote as a bloc, the Democrat who carries black voters usually wins the nomination. On Wednesday three candidates in particular were vying for their support: Biden, who has community support because of his partnership with President Obama; Harris, who has sought to build a base of black women; and Senator Cory Booker, the former mayor of Newark, N.J., who has emphasized criminal-justice reform. A Quinnipiac poll released Monday found Biden leading with support from 53% of black voters, with all of his opponents trailing in the single digits.

But the voters sitting on folding chairs watching the debate didn’t necessarily seem pulled towards any of them. Between Harris, Biden, and Booker, no clear favorite emerged. Instead, these Flint voters seemed drawn to candidates like businessman Andrew Yang and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard. In interviews, they seemed simultaneously overwhelmed with their choices and bored by their options. During the roughly 40-minute stretch of the debate that focused on the policy minutiae underpinning various Medicare for All plans, many of the voters were scrolling on their phones.

Even the issues that campaigns suspected would pique their interests didn’t seem to galvanize the crowd. A long back-and-forth between Biden, Booker, and Harris on their respective criminal-justice records drew only a muted response. Despite heated online debates about criminal justice, nobody in the Flint room volunteered opinions about Biden’s 1994 crime bill, or Harris’s time as a prosecutor, or Booker’s criminal justice reform bill.

Amber Hassan, a 38-year old Flint hip-hop artist, said she wasn’t particularly impressed with any of the front-runners on Wednesday night. “I’m waiting for Kamala Harris to represent everyday black women,” she said, “I’m not talking about PhD black women, I’m talking about everyday, middle America, regular struggles black women.”

Biden, she added, “feels entitled to it, there’s an air of ‘I’ve kind of got this in the bag, I’ve done this before,'” she said. “No, you haven’t done this before: you’ve been the assistant.” Booker, she said, didn’t seem “authentic.”

But Hassan said she was intrigued by “the blonde woman”—meaning Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, who talked during the debate about how, as a white woman, she could be a messenger to her peers about matters like white privilege. And she was drawn to Yang: “I liked that he was a little more relaxed. He didn’t have a tie on.”

Overall, these voters responded best when the candidates involved the challenges facing their community in Flint. They nodded when Booker argued that Trump won Michigan partly because of the suppression of black voters. They cheered when Yang pointed out that “we automated away 4 million manufacturing jobs, hundreds of thousands right here in Michigan.” They clapped when Gabbard suggested redirecting trillions of dollars away from “wasteful regime change wars” and towards “making sure everyone in this country has clean water to drink.”

But the skepticism towards the establishment ran deep, especially in a community that has been as failed by elected leaders as badly as Flint has. They were unimpressed by lip service that didn’t come with an infrastructure plan or a promise of increased funding. “Everybody uses us, because it looks good,” said Shanta Smith, 43, who runs a Flint substance abuse facility. “They’ll drive through Flint, they’ll touch on it, but what are you really doing for Flint?”

Smith came to the debate thinking he wanted to hear from Harris or Booker, but found himself listening closely to Yang. “He was really talking about real issues, not just attacking and playing the politics game. He had his math together,” said Smith. “He’s not the usual candidate.” Other voters at the watch party agreed: in an informal poll conducted after the debate, Yang won overwhelmingly.

Some voters did voice support for the big names. “Kamala impressed me right out the gate because our community needs somebody who is in touch,” said Michele Kelly, 60. She liked Booker too, she said, because he lived in a low-income community in Newark. “You don’t do that for show,” she said. “If you go and live in low-income housing, that means you love the people who are there.”

Some voters said that if nobody captures their trust, they may not vote at all. Amber Hassan, who calls herself a “selective voter,” says choosing between two imperfect candidates is like choosing between “dirty lettuce or rotten lettuce,” and she’d rather walk away with nothing.

“We’ve been lied to so many times,” says Lendra Brown, 59, a former food stamp manager. If she had to vote tomorrow, she says, “I would vote for Mickey Mouse.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlotte Alter/Flint, Mich. at charlotte.alter@time.com