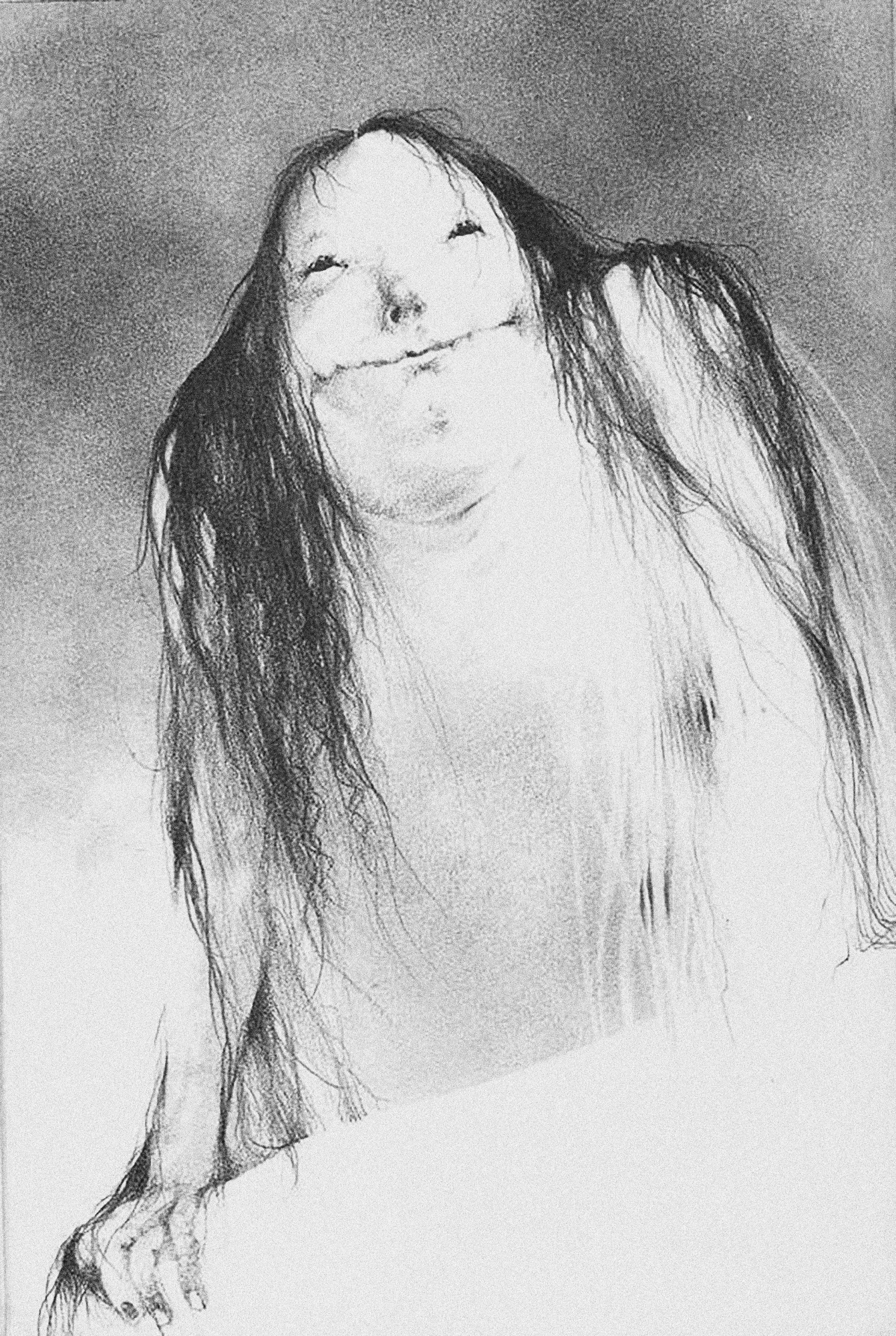

The new movie Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, from André Øvredal and Guillermo del Toro, has kids of the ’80s and ’90s reminiscing about the terrifying source material. Written by Alvin Schwartz—and distinguished by Stephen Gammell’s gruesome illustrations—the original series of Scary Stories books (published in 1981, 1984, and 1991) were fervently swapped at school libraries and sleepovers alike. To Schwartz’s readers, hitchhikers, scarecrows, skin bumps, and green ribbons never looked the same.

Upon reexamination in the light, these stories are as simple and plainly told as folktales and urban legends. Which is exactly what they were. Schwartz, the man behind your childhood nightmares, was in fact a scholarly folklorist, author of more than fifty books, and the father to four children, who helped him to develop his work. As the children’s literature scholar Sylvia M. Vardell writes: “Who has done for folklore for children in the United States what the Grimm brothers did in Germany…? Alvin Schwartz, that’s who!”

Schwartz began collecting folklore in the early 1970s, conducting extensive research and interviews to uncover engaging tales. In a Q&A for Language Arts, Schwartz tells Vardell that his process involves learning everything he can about a genre, discussing each topic with scholars and folklorists, and doing extensive research at Princeton University’s Firestone Library. “What’s interesting is that eventually patterns emerge,” he says.

In working with “scary story” material, one finds five or six or seven typologies. I was not aware of this with Scary Stories until I began searching the material and putting it together. Sometimes I will go so far as to study the structure of an item to see how it works, because this is important in making selections.

He also reveals that he thinks of all his stories as oral folktales. His process, therefore, includes reading his writing aloud to himself in the bathroom (“because the acoustics are so good”) three or four times to make sure it all sounds right. (Let’s hope he didn’t experience what the movie’s trailer suggests: “If we repeat stories often enough, they become real.”)

So why are these stories so uniquely terrifying? And why have kids devoured them throughout the decades? Schwartz claims to just follow his gut when it comes to figuring out what kids will like. He also acknowledges that stories once written for adults, like the chilling tales in Scary Stories, now work for children, since kids have “gotten so sophisticated.” This comment, however, was made in 1987, and it’s worth noting that after years of PTAs and concerned parents banning the Scary Stories series, they were re-released with much gentler illustrations. It’s hard to say whether this is reflective of kids’ or adults’ levels of “sophistication.”

The education scholar Randi Dickson writes about her 6-year-old’s love for the Scary Stories books in her essay “Horror: To Gratify, Not Edify.” Dickson points out that the paradox of the horror genre appeals to children for the same reason it appeals to adults: there is both the “fascination with the monster, and interest in the narrative structure.”

Dickson shares the theory that a fictional world of monsters provides children with a relatively secure place to face their real fears. She also cites the scholar Noel Carroll, who suggests that “the great lure of horror fiction comes from a combination of awe and curiosity about what is unnatural and repulsive.” Another theory, put forth by the scholar Ruth Vinz, is that horror forces kids “to consider a world beyond the one that exists in their daily lives.” Put more simply, as the great scholar Frog says in Days with Frog and Toad: “Don’t you like to feel the shivers?”

So, are Scary Stories too scary for today’s kids? And is there any point in allowing kids to read this kind of thing? As Schwartz puts it, the value is in the tales’ history as folk stories:

There’s something remarkable about all these people who don’t see themselves as especially talented… having created all this wonderful material. This, to me, is very exciting. I think it can be reinforcing for kids who are having problems—problems with self-confidence—to understand that folklore is something that unknown ordinary people have created as expressions of some of their innermost feelings.

The cinematic Scary Stories unites the stories with an overarching plot (a “frame,” as our folklorist friend might call it) in which teenagers find a haunted book that writes itself based on its readers’ worst fears, which then become real. (The film’s website even includes an interactive feature allowing users to create their own scary stories.) Looks like Schwartz’s concept that ordinary people create scary stories from their innermost feelings is going to get some air time after all. Shiver.

This article appeared on JSTOR Daily. Read the original article here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com