Planets are like puppies—they come in all kinds of sizes, all kinds of colors and they’re often found in litters.

That’s not the way things used to seem. It wasn’t until 1992 that the first known planet orbiting a star other than our sun was confirmed. In the years since, the exoplanet population has exploded, thanks mostly to the Kepler Space Telescope, which went aloft in 2009 and, before it at last went off-line in 2018, had discovered 2,345 confirmed exoplanets and identified another 2,420 candidates still awaiting confirmation.

Now, a successor to Kepler has made its own mark. In a paper published in Nature Astronomy, investigators announced the discovery of a trifecta of new planets in a single go, all of them orbiting a star just 73 light years from Earth—or one town over on the scale of the universe. What’s more, two of the planets are a sort of cosmic equivalent of an evolutionary missing link, with a size and mass that lands in between those of the planets in our own solar system.

While Kepler’s planetary haul was huge, many of the worlds it discovered lie thousands of light years from Earth. With a single light year measuring 5.88 trillion miles, it’s hard to determine much about any of the new worlds except their diameter, mass and the speed at which they orbit their parent star. That’s not nothing: all of those metrics can allow astronomers to determine the planets’ temperature and likely makeup—rocky like Venus and Earth or gaseous like Saturn and Neptune. And those factors provide hints as to whether the planets are habitable.

But hints aren’t answers, and to get more of those, NASA launched the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) in 2018, with the goal of finding planets orbiting stars much closer to Earth, making it easier to study such details as the composition of their atmospheres, assuming they have one. TESS works the same way Kepler worked, essentially by gazing fixedly at a star, waiting for tiny dips in the light it emits, indicating that an orbiting planet is passing in front of it. The degree of the dimming indicates the diameter of the planet and the frequency of the light dips can be translated into the speed of the planet’s orbit. While Kepler’s optics were designed to look at a single patch of sky deep in space, TESS will scan the 360-degree bowl of the sky and limit its survey to comparatively local stars.

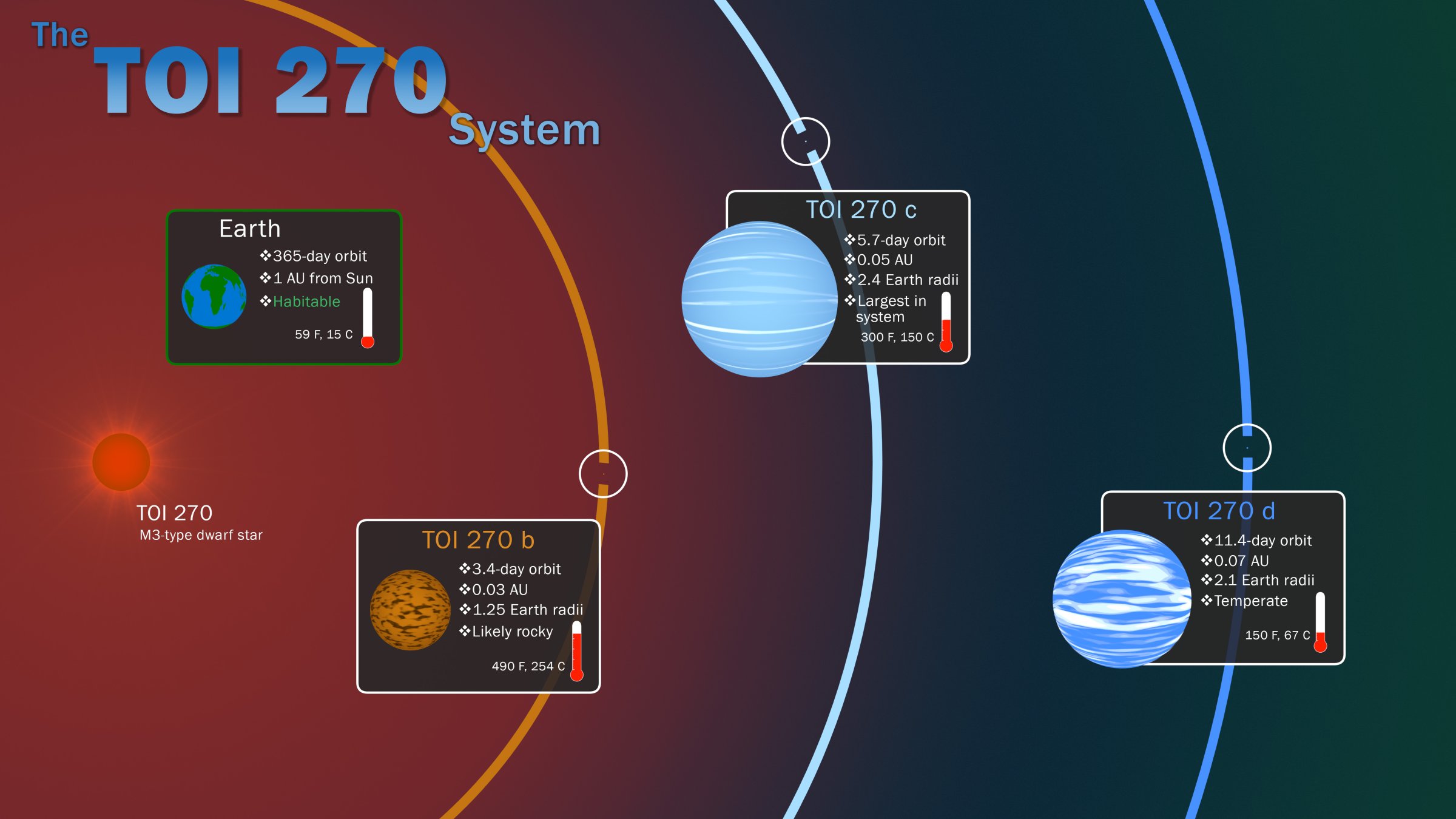

As reported in the new study, TESS spotted a trio of planets orbiting a dwarf star known as TOI 270. The TOI means “TESS Object of Interest” and while the star is actually not very interesting at all—a relatively dim bulb just 40% the size and 33% the temperature of our sun—the planets are another matter.

The innermost of the three, TOI 270b, is just 2.79 million miles from its sun, an arm’s reach compared to the 93-million mile remove at which the Earth orbits the sun. At that close range, the planet fairly sprints through its orbits, completing a single revolution—AKA one year—in 3.4 Earth days. TOI 270b is likely rocky, like Earth, and only about 25% larger than Earth, but after that, the similarities stop. The blowtorch fires of the close-up star have all but certainly blasted away any atmosphere the planet may once have had, and the surface temperature averages an estimated 490º F.

The planet’s bigger siblings, TOI 270c and TOI 270d, sit farther away—4 .65 million miles and 6.51 million miles respectively. They are also bigger, 2.4 and 2.1 times the radius of Earth. The larger size and greater breathing room makes an enormous difference in their nature. Both are gas worlds, like the four outer planets in our solar system, and indeed are informally characterized by NASA scientists as “mini-Neptunes.”

“An interesting aspect of this system is that its planets straddle a well-established gap in known planetary sizes,” said Fran Pozuelos, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Liège in Belgium who was a co-author on the paper, in a statement released by NASA. “TOI 270 is an excellent laboratory for studying the margins of this gap.”

Of the two little Neptunes, TOI 270c is the less hospitable, with temperatures of about 300º F; but TOI 270d is an almost-comfortable 150º F, and in the higher reaches of its atmosphere it would be cooler. Depending on the mix of gases in that upper atmosphere, it’s possible the planet could host some biological processes.

“This system is exactly what TESS was designed to find: small, temperate planets that pass in front of an inactive host star,” says researcher Maximilian Günther, of MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

Finding such planets is one thing; studying their chemistry from a distance of 73 light years is something else entirely. That requires a telescope that can not not only find the planets as they pass in front of their stars, but analyze the starlight as it streams through the planets’ atmospheres, providing a chemical fingerprint of the gasses. TESS doesn’t have the ability to do that, but the oft-delayed James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled for launch in 2021, will.

Webb, if and when it does launch, may or may not find life. But with perhaps 250 billion stars in the Milky Way and up to 100 billion galaxies in the universe, and with virtually every star now thought to have at least one planet, there are trillions of places to look. For scientists hunting for life, it only takes one.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com