The words spoken by astronaut Neil Armstrong when he became the first man to step foot on the moon — at 10:56 pm Eastern Time on July 20, 1969 — have since become one of the most famous sentences ever uttered.

But NASA’s Mission Control staffers in Houston were moved by a different line, spoken about six hours earlier.

Shortly after 4:05 p.m., the words came across from Armstrong’s fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin, as the astronauts were looking for their landing spot: “Picking up some dust.”

“When he said that, it sent a chill up my back,” says Gerry Griffin, who was then a 34-year-old flight director. “In fact, I just got the same chill again. It was the first time humans had ever been in a spacecraft with a rocket engine blowing particles off the surface of some place that wasn’t Earth. After that, it felt kind of anticlimactic to me.”

Inside the Mission Operations Control Room — a freezing-cold space in Houston that smelled like coffee and so much tobacco that a cloud of smoke would draft out when the door opened — that dust meant the landing was no longer theoretical. It was going to happen.

Ed Fendell, nicknamed “Captain Video” because he operated the communications system for the “mothership,” the command module, recalls that he felt as if he himself were weightless as soon as he heard those words: “Here we are, the first attempt to land, and I felt like I was levitating over the chair. I didn’t feel like I was touching the chair, or the ground with my feet.”

When three of the footpads of the lunar module nicknamed Eagle touched the surface of the moon, a light flashed. In Houston, Aldrin’s voice could be heard confirming the step: “Contact light.”

Jack Knight, who was a 25-year-old flight controller who monitored the lunar module, gets choked up when he recalls that line 50 years later. “Then, I knew they were going to land,” he says, in tears.

At 4:18 p.m., Armstrong radioed: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Charles Duke, the 33-year-old spacecraft communicator or CAPCOM, responded: “Roger.” Then, after garbling Tranquility as “Twang-quility,” he continued, “We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

For everything happening off earth all in one place, sign up for the weekly TIME Space newsletter

‘I Never Felt So Proud’

“I was so excited, I couldn’t even say Tranquility,” Duke says. “The tension evaporated [after that].”

Fifty years later, Duke says he found it “easier” to be the one actually landing a spacecraft on the moon — which he did during Apollo 16 in 1972 — than to monitor this one from Mission Control down on Earth. “I was much more confident and relaxed” in space. “You’re looking out, seeing it, feeling the spacecraft as it maneuvers, [rather] than looking at charts and lines on a computer screen.”

But the successful landing didn’t mean the astronauts were out of danger.

As people around the world began to celebrate, the men in Mission Control knew their work wasn’t yet done. The 35-year-old flight director Gene Kranz, whom TIME described as “a crew-cut and clip-voiced former test pilot,” started to get annoyed by the whooping and hollering of the VIPs in the viewing room behind him. “They start cheering and stomping their feet, and that sound seeps into the room at a time when we have to concentrate,” he says. “I get sort of angry. I sort of yelled at everybody to settle down.” He even broke his pencil and it flew up in the air. The crew still had to do the post-landing checklist.

“The crew has just landed,” he explains, “and we have to make sure it is safe to remain there and we have to do it at very specific times, when the lunar module could lift off and do a rendez-vous with the command module that’s orbiting the moon.”

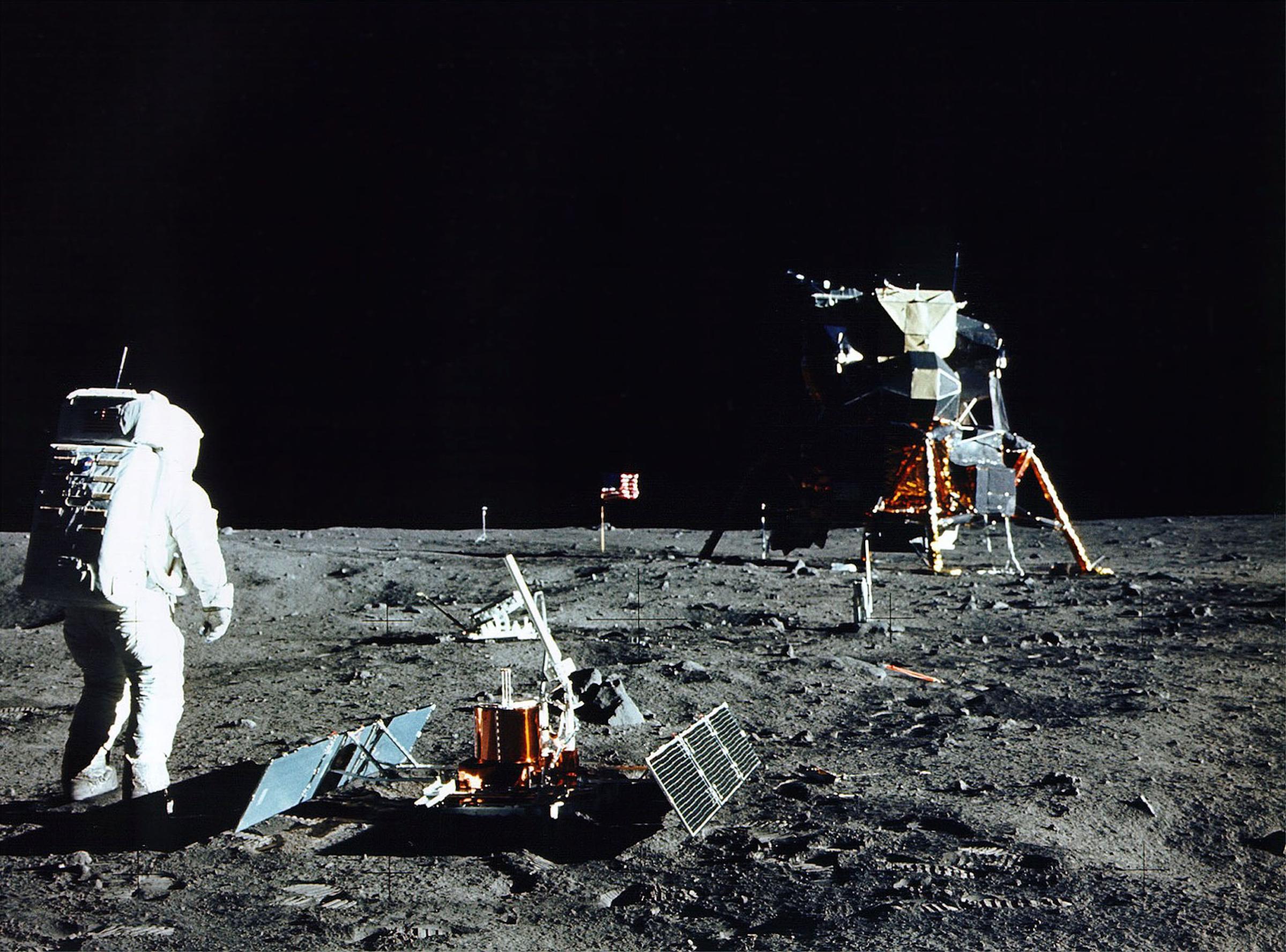

After getting the clear that it was safe to stay, Neil Armstrong climbed down the ladder of the lunar module and spoke his famous words. Pete Conrad, who would become the third man to walk on the moon during Apollo 12, had come to watch and remarked that it was “just like Armstrong to say something profound like that,” remembers Jerry Bostick, who back then was the 30-year-old leader of a team of flight controllers in “the trench,” the nickname for the first row of consoles.

John Aaron, who was a 26-year-old subsystems flight controller for the command module, was done with his shift after the landing, but didn’t want to go home yet. He stepped outside for a cigarette. On that humid evening, the man with a reputation for sangfroid looked up at the sky in a new way.

“I was looking at the moon, the real moon, and I just felt, Oh wow. There it is. We’re there. That’s when it really hit me, the emotional drain,” he says. “When they actually landed, I remember the hair on the back of my neck standing up just a little bit, but when I saw the moon, it was just…wow.”

The morning after the astronauts walked on the moon, two guys who worked at the gas station nearby approached Fendell while he was eating scrambled eggs in a coffee shop. “One of them said, you know, I landed in Normandy on D-Day, and I never felt so proud to be an American as I was yesterday,” Fendell tells TIME. “And it finally hit me as to what we had done. It hadn’t really registered [to me] what it meant to the outside world. I threw my money down, went in my car and cried in the car.”

The Long Road to the Moon

Some of the Mission Control staffers had been waiting for this moment since the Space Race started.

Griffin served in the U.S. Air Force but had set his eyes on NASA when he saw Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin become the first man in space on April 12, 1961. Flight dynamics officer Dave Reed built model airplanes growing up, but switched to rockets when he was 15 after watching the Soviet Union become the first country to successfully launch a satellite on Oct. 4, 1957. And watching the Saturn V rocket launch the Apollo astronauts into space was like coming full circle for flight controller Charles “Chuck” Deiterich, the son of an airport mechanic who drew pictures of rockets in junior high school; he ended up computing the throttle-down time for the lunar module’s descent to the moon’s surface and the maneuvers for the astronauts’ return to Earth.

The average age of the Mission Operations Control Room was 28, and the learning was all on the fly. After all, none of this had been done before.

“I’m like an orchestra conductor,” Christopher Columbus Kraft, Jr., flight operations director for the Apollo missions told TIME back then. “I don’t write the music, I just make sure it comes out right.” The “windowless” Mission Operations Control Room was his “unlikely podium” on the third floor of Building 30 at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center, TIME reported. The flight controllers wee “his musicians,” sitting in “four rows of gray computer consoles, monitoring some 1,500 constantly changing items of information registered on gauges, dials and meters.”

The Mission Control staffers had gotten to know the astronauts well too, working closely with them during simulations and in mission-planning meetings. In fact, Armstrong went to visit Bostick when he got back from the post-moon world tour. (Armstrong arrived when Bostick was napping, and the flight controller’s son closed the door on the astronaut, who later told Bostick that he got a good laugh out of it.) But as these work relationships became tighter, some staffers grew farther apart from the other people in their lives. Aaron jokes that he and his wife technically had two kids at the time, “but she raised three,” because he had so little time to do anything for himself. Apollo meant many nights eating dinner at work and sleeping in the Mission Control Center’s sleeping quarters. Reed’s marriage ended after the moon landing, and so did Bostick’s.

“Apollo 11 is the dividing point in my personal life,” says Bostick.

Looking Back

The flood of nostalgia and commemoration that has accompanied the 50th anniversary of the landing has prompted those who saw it up-close to reflect on how it happened — and what’s changed since then. Many of the men who were behind the scenes are now front in center in interviews and archival footage re-released, such as the 2017 documentary Mission Control: The Unsung Heroes of Apollo, and the 2019 documentaries Apollo: Missions to the Moon and Apollo 11.

The biggest difference between then and now, they say, is a matter of the technology that the space program works with. “Oh my goodness gracious, we had more software in a flip phone in 2004 than we lifted off with. That to me is stupendous,” says Reed.

The qualifications to work at NASA, especially as an astronaut, have also grown astronomically. “Today, I wouldn’t even be considered as an astronaut,” says Duke. “I don’t have a Ph.D. The astronaut program is harder today, and a lot more science is required than we had to learn. It’s all for the good, too.” He hopes that the 50th anniversary will inspire people to go into STEM fields. By comparison, five decades ago, “When you came to work here, no one handed you a workbook, no one gave you a class. There weren’t any,” says Fendell. Flight Director Glynn Lunney confirmed that the higher-ups would say, “We don’t have manuals. We’re looking for you to write the manuals.”

And they’re eager to see Americans get back to the moon.

During the final Apollo mission, Apollo 17, in December 1972, Griffin remembers shooting the breeze with a bunch of guys huddled around his desk, disappointed about the program ending, and telling them to cheer up by saying that by the early 1990s they’d be on Mars, so not to worry about the lack of future missions to the moon. “So don’t ask me to predict the future of spaceflight,” he says, “because I was not accurate at all.”

The aptly named Bill Moon, who sat in a staff support room that assisted the Mission Operations Control Room, laments the irony of working so hard to beat the Russians and now relying on them to get American astronauts to space. “I’ll be glad when we start having our own ride and not having to depend on the Russians,” he says. “It’s a matter of pride.”

When that happens, the men who watched it happen for the first time will be eager to see it again.

“Now,” Deiterich says, “I’m more excited about it than I was at the time.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com