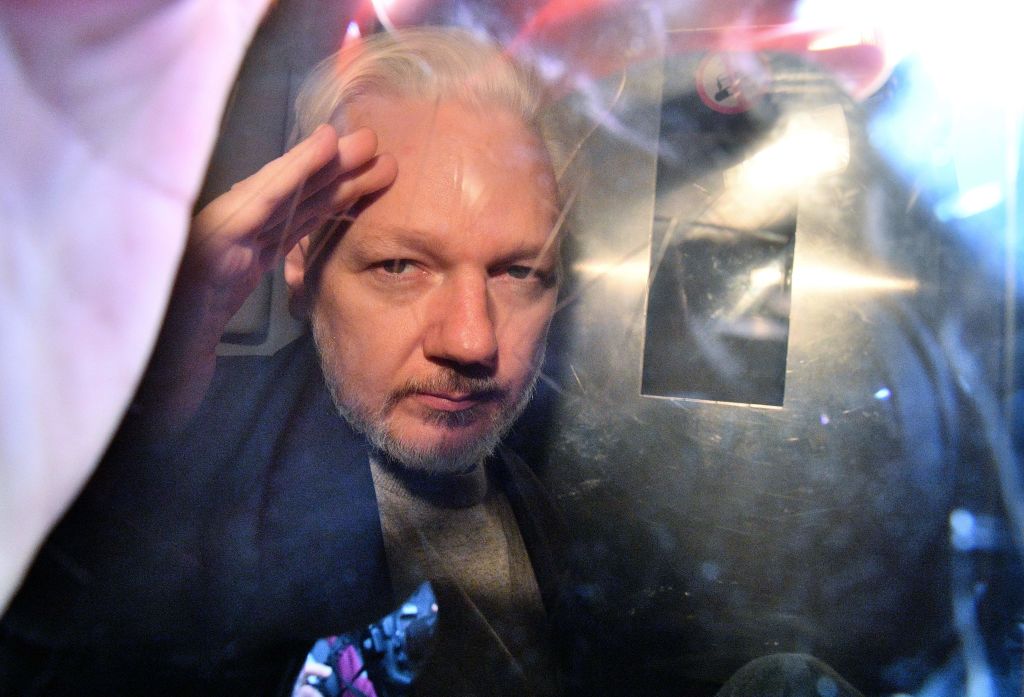

Julian Assange appeared in a British court Friday in the first of what is likely to be many battles over a recently filed U.S. extradition attempt. Speaking via video link from a maximum-security prison near London, the 47-year old WikiLeaks founder declared that “175 years of my life is effectively at stake,” while banner-waving supporters demonstrated outside Westminster Magistrates Court.

It was typical theatrics surrounding Assange, a man who has achieved worldwide notoriety for his commitment to exposing closely held national security secrets. But the supporters who paint him as a victim of far-reaching government power aren’t wrong about one thing. The U.S. has gone further in the charges it brought against Assange than any prior American government, putting into motion a legal process that has sweeping implications for the First Amendment’s bedrock protection of free speech.

Late last month, the Trump Administration filed an 18-count indictment that included charges Assange had violated provisions of the Espionage Act by publishing one of the largest troves of classified documents in U.S. history. It is the first time the federal government is prosecuting a defendant for receiving and publishing still-classified information.

That extraordinary step sets up what may be a bitter irony for the U.S. government. By choosing to use the Espionage Act as aggressively as it has, rather than sticking to a single count of computer hacking, American prosecutors may have ensured that Assange will never see justice in the United States. Foreign governments have tended to view espionage as a political crime, says Jameel Jaffer, executive director for Columbia University’s Knight First Amendment Institute, and it would be highly unusual if Britain extradited Assange to face charges under the Espionage Act. “Countries don’t ordinarily extradite individuals facing prosecution for political offenses,” he said.

Even without the challenges posed by the Espionage Act, extraditing Assange promises to be a protracted, politically charged process that faces long odds. Human rights groups, such as Amnesty International, have already called for the extradition request to be dismissed. Additionally, any ruling against Assange will almost certainly be appealed to Britain’s Supreme Court, which takes time. For instance, two men — suspected hacker Lauri Love and banker Stuart Scott — won their appeals against extradition last year to the United States after fighting the cases for several years.

Regardless of what happens next, the indictment should be perceived as an ominous threat to newsgathering and journalism, Jaffer said. “The U.S.’s indictment of Assange should be understood as an assault on press freedom, because the theory of the indictment is that routine practices of investigative journalism are criminal,” he said. “Cultivating sources, communicating with sources confidentially, protecting sources’ identities, and publishing government secrets — this is what good national security journalists do every day.”

What’s now at stake, constitutional lawyers say, is how far the First Amendment extends to protect journalists who publish information they deem to be in the interest of the American public, even if that information is secret.

In recent years, the most publicly significant national security stories exposing problematic government behavior, including revelations of CIA black sites, the torture program, and NSA domestic surveillance practices, were based on secret information. Publication of these stories led to sweeping reforms in U.S. policy. The danger of going after Assange, civil libertarians say, is an attack on Americans’ right to know about what the government does with taxpayer dollars in America’s name.

The Justice Department argues Assange is not a journalist. Journalism advocates say that makes the case even more dangerous, because the Espionage Act doesn’t differentiate between reporters and everyone else. That in turn means a successful prosecution of Assange will set the precedent for prosecuting journalists as spies down the road.

Another complicating factor is that news organizations, such as the New York Times, The Guardian and Der Spiegel, published information in partnership with WikiLeaks, including material leaked by U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning. That raises the possibility that they, too, could be potential Justice Department targets if the Assange case proves successful.

This is why the Administration’s pursuit of Assange “crosses the Rubicon” on Espionage Act prosecution, says Stephen Vladeck, a national security law professor at the University of Texas at Austin, who has followed the casework on the issue for more than a decade. It was Trump’s predecessor, Barack Obama, who launched a deliberate campaign to find, expose and prosecute the leakers in order to deter others from taking similar actions. “The difference, I think, is the Obama Administration was always mindful of the dangerous precedent of breadth of the Espionage Act,” Vladeck said.

“Trump’s DOJ is acting more aggressively, but it is building off of a blueprint set out by the Obama Administration, including dusting off old cases that were left to die on the vine and bringing new ones using and expanding legal precedents set during the Obama Administration,” says Jesselyn Radack, a national security and human rights attorney who specializes in representing whistleblowers. She now represents Daniel Everette Hale, a 31-year old former Air Force intelligence analyst, who was charged in May for violating the Espionage Act.

“The Trump Administration wants quell information that it does not want the public to know, especially information that exposes government fraud, waste, abuse of power and illegality, i.e. classic whistleblowing disclosures that have exposed this countries darkest atrocities: war crimes, torture, and secret domestic surveillance.”

The U.S. government’s aggressive prosecution of leaks and efforts to control information are already having a chilling effect on journalists and government whistle-blowers. Many journalistic sources, including those of TIME, have shifted to encrypted means of communication or don’t engage at all as a result of the Assange indictment.

Assange’s appearance Friday came less than a month after the U.S. filed its indictment in the Eastern District of Virginia. The U.S. had 60 days from Assange’s April 11 arrest at the Ecuadoran Embassy in London to send the a formal extradition request under an extradition treaty with Britain. The judge set February 25, 2020 as the date for a full hearing on whether he will ever be sent to face charges in the United States.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to W.J. Hennigan at william.hennigan@time.com