Standing in a wood-paneled room at the University of Oxford, surrounded by her artwork, Ai-Da looks out at her creations. “I want people to know that our times are powerful times,” she says slowly, pausing between sentences. Like many artists, she wants her work to promote discussion. And yet unlike other artists, Ai-Da tells us with a blank expression and glassy eyes that only blink occasionally, she does not have consciousness, thoughts and feelings. At least, not yet.

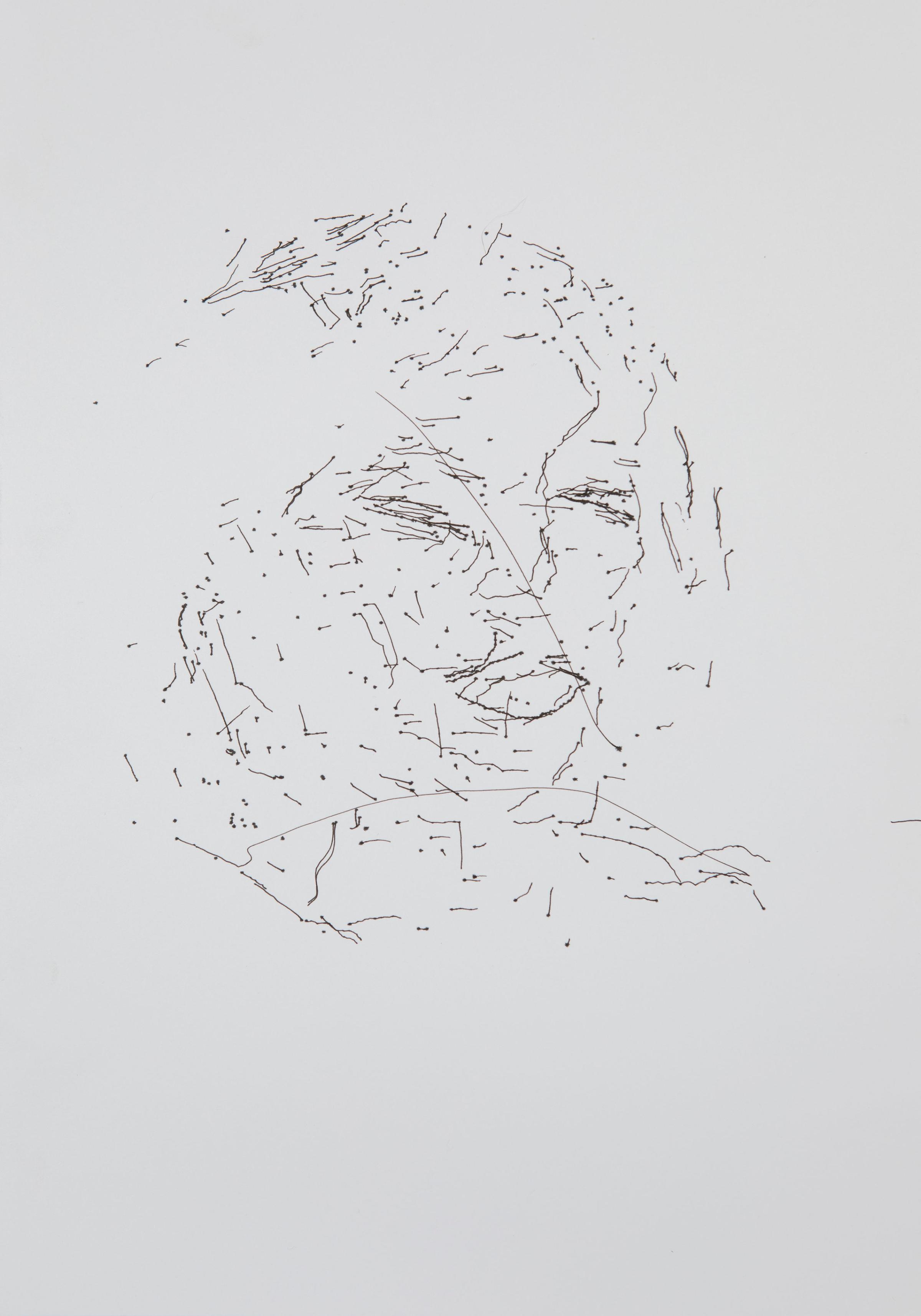

Ai-Da’s creators bill her as the world’s first robot artist, and she’s the latest AI innovation to blur the boundary between machine and artist; a vision of the future suddenly becoming part of our present. She has a robotic arm system and human-like features, is equipped with facial recognition technology and is powered with artificial intelligence. She is able to analyze an image in front of her, which feeds into an algorithm to dictate the movement of her arm, enabling her to produce sketches. Her goal is creativity.

She is currently on display at Oxford in what organizers say is the world’s first exhibition to show the solo work of a robotic artist. Using academic Margaret Boden’s philosophical definition of creativity as something that is new, surprising and of value, art dealer and leader of the Ai-Da project Aidan Meller believes Ai-Da’s output meets these criteria. He tells TIME that each of the robot’s creations are different every time, even with the same stimulus, and are unreproducible.

Manufactured by a team of engineers specializing in robots with human-like features and using algorithms developed by scientists at Oxford University, Ai-Da captures images in front of her with a camera in her eye. A series of algorithms then send instructions to her robotic arm and hand, which was created by students based in Leeds, U.K. Ai-Da takes her name from Ada Lovelace, the world’s first female computer programmer, and the exhibition at Oxford is a homage to the history of AI and robotics. The art on show includes drawings, paintings and sculptures rendered from her algorithmic instructions.

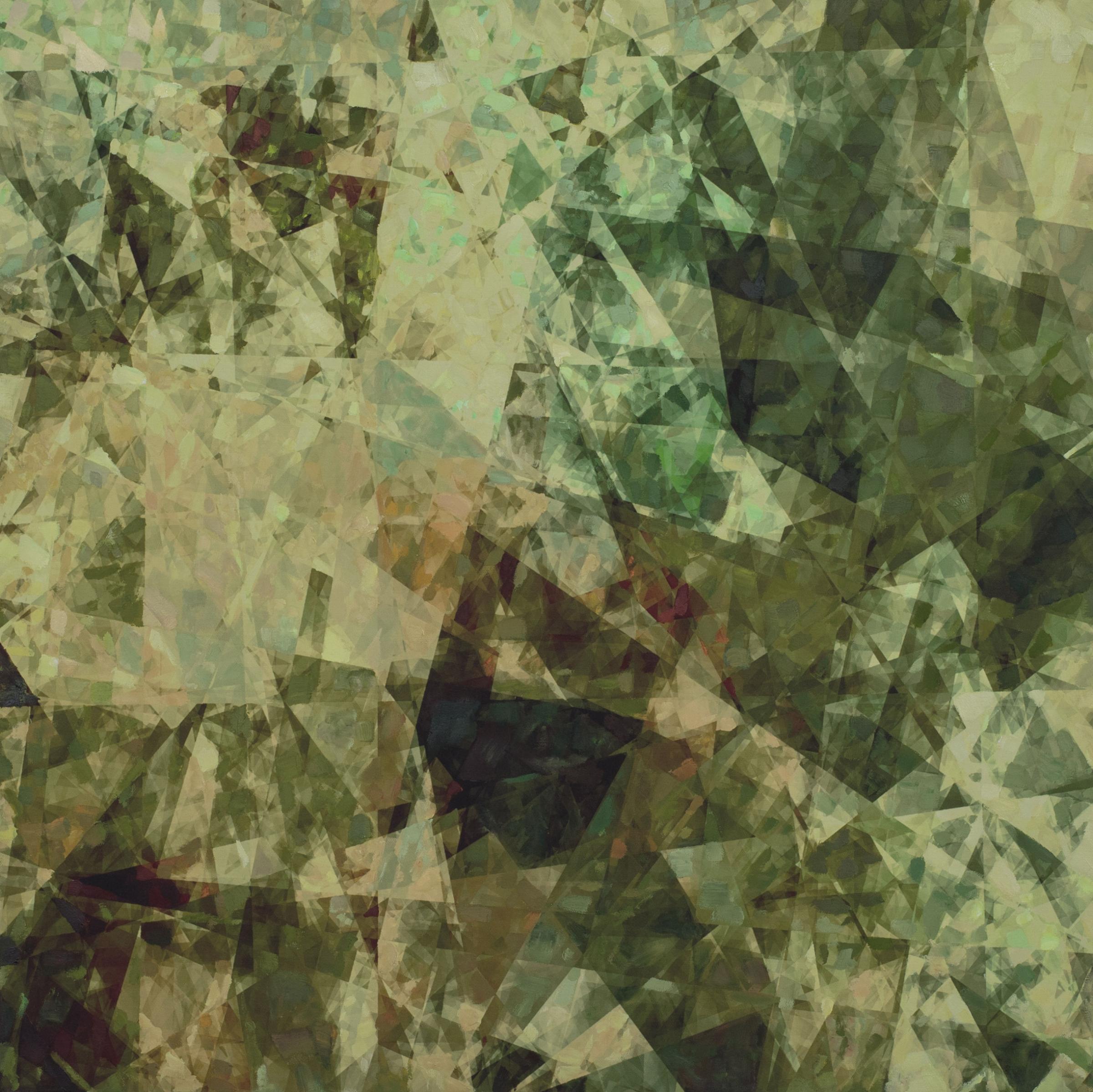

To create the prism like paintings, Ai-Da draws a picture, for example a bee or a tree. Researchers at Oxford University plot the coordinates from her drawing onto a Cartesian plane (a graph), and run them through an AI neural network, a computing system modelled on the human brain. The choices of the neural network and the way it ‘reads’ the drawing coordinates create the dazzling prism effect, as neural networks interpret the Cartesian plane very differently to humans. The complex visual output is printed onto canvas, where a human artist then paints over part of the canvas. “The potential for technology to augment the human potential for creativity, to expand the achievable horizons of creative expression and to possess its own creative potential as an entity of its own is so fascinating and exciting,” says Aidan Gomez, a researcher at Oxford working on the project.

Also on show at the exhibition are pencil sketches of Alan Turing, the famed pioneer of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence, and Karel Čapek, the Czech writer who coined the term “robot,” as well as abstract paintings that have been created using Ai-Da’s AI response to stimuli of an oak tree and a bee. Monitor screens around the exhibition show Ai-Da reciting poetry that has been created by rearranging the work of incarcerated writers of the 20th century exploring the pain and suffering of imprisonment, like Oscar Wilde and Fyodor Dostoevsky. There’s something slightly unnerving about her renditions of their reinterpreted works, her hesitant voice speaking on behalf of the imprisoned.

“We see this show as the start of a journey questioning the uses and abuses of AI and machine learning,” says Meller, who has over 20 years’ experience in the art industry. “Without a doubt, AI is going to be the big thing of the 2020s, and that concerns us greatly. The 20th century shows that when there is technological development, small groups of people can get hold of that with devastating effects.”

Ai-Da is not the first AI creation to produce artwork. Last year, Christie’s New York auctioned an AI-generated work in the first sale of its kind at a major auction house, and since 2006, British computer scientist Simon Colton has been developing creative graphics software to turn digital photographs into works of art.

But Ai-Da’s human-like appearance brings something both intriguing and slightly eerie to the field. “Through the project, I’ve noticed how robotic we are as humans,” Meller says. “Ai-Da’s become such a phenomenon because you can’t pigeonhole her; she’s not just one thing, she’s many. As a result, we’ve produced lots of works that are by her, and her nature.”

Many of us have long been fascinated by the crossovers between, and potential combination of, man and machine. Recent examples include Yuval Noah Harari’s exploration of biotechnology’s impact on humans in Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, and viral sensation Sophia, dubbed “the world’s most human-like robot.”

“What’s intriguing here [with Ai-Da] is that people get very taken in by a robot that looks human,” says Marcus du Sautoy, a professor of mathematics at Oxford University and author of The Creativity Code: How AI Is Learning to Write, Paint and Think. Indeed, one art critic appeared to be so smitten by Ai-Da’s lips and her eyes that he lamented not being able to write his phone number on her metallic robotic hand.

That fascination with Ai-Da’s appearance may be somewhat distracting from the substance and skill of her art. “Actually for several decades, there have already been examples of great algorithmic art, which hasn’t needed a human robot to achieve that,” du Sautoy points out. Du Sautoy, like Ai-Da’s creators, is optimistic about the combination of AI and creativity, particularly when it adds value and is surprising, as Boden’s definition suggests. “Machine learning is all about picking up unique characteristics in data, and being able to exploit that to produce more, or to take things in a new direction,” he says. “The challenge is not to create things that are more of the same. The most impressive cases are where AI is pushing us up as humans into the new.”

As an example of AI pushing the human boundaries of creativity and helping us to discover new things, Du Sautoy cites the Continuator, a musical instrument trained to respond to users. . In 2012, French jazz musician Bernard Lubat improvised with the Continuator, which was trained in his style of musicianship, leaving audiences unable to distinguish the difference between the machine and the musician. “The really fascinating thing is that Lubak said when he was improvising with the AI, it was doing things he had never thought of doing with his musical soundscape, and was pushing him to develop ideas that would have taken him years to develop,” says du Sautoy.

However, the rapid innovation in this field can come with pitfalls. Du Sautoy used an algorithm to write 350 words of his own book, material he says nobody, including his editor, has been able to yet identify as computer-generated. The fact that the AI-generated text is indistinguishable from human prose could one day lead to misuse of the technology. But du Sautoy says that that is a long way off, as AI is having difficulty with long term structures in writing text and language. Other shortcomings include the hidden biases that can creep into algorithms, such as racial biases. In other words, as du Sautoy points out, machines may be learning to be creative, but they could potentially be learning from bad or biased data.

“There’s a potential for AI to help us create a new sort of art. That’s as exciting as when the camera came along,” du Sautoy says. Indeed, early photographers were seen more as inventors or pioneers of the cumbersome, mechanical process used to capture images in the late 19th century. That’s quite a contrast to today, as technological developments have enabled photographers to be seen as artists in their own right. “Ultimately, I think AI one day will become conscious, and really good AI art will appear when the intentionality is coming from the computer and it has a need to tell us what it feels like inside.”

Ai-Da’s creators hope that this exhibition is just the start, and eventually want her to create her own brushwork paintings and artwork that humans physically cannot complete, such as highly complex and detailed canvas work. And as for Ai-Da herself; she cites Yoko Ono, George Orwell and Aldous Huxley as her inspiration. “If we can learn from things in the past,” she says, tilting her head and adjusting her line of vision, “maybe we can make our future a little brighter.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com