The British and Americans have never gotten along very well where the English language is concerned. British mockery and indignation over what Americans were doing with and to the language began long before Independence, but after that it blossomed into a fully-fledged, ill-spirited, relentless attack that is still going on today. The conservative British politician and Brexit supporter Jacob Rees-Mogg, for example, has been defended as “one who dares to eschew the current, Americanized, mode of behaviour, speech, and dress.” In our own time, as has been the case for more than two centuries, fights about nationalism easily turn into skirmishes over language.

British ridicule of American ways of speaking became a vitriolic and crowded sport in the 18th and 19th centuries. New American words were springing up seemingly out of nowhere, and the British had no clue what many of them meant. Although he greatly admired America and Americans, the expatriate Scottish churchman John Witherspoon, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and member of Congress, had no taste for the language he heard cropping up in all walks of life in the country. “I have heard in this country,” he wrote in 1781, “in the senate, at the bar, and from the pulpit, and see daily in dissertations from the press, errors in grammar, improprieties and vulgarisms which hardly any person of the same class in point of rank and literature would have fallen into in Great Britain.” Among the Americanisms he said he heard everywhere were the use of “every” instead of “every one” and “mad” for “angry.” He particularly disliked “this here” or “that there.”

The British cringed over new American accents, coinages and vulgarisms. Prophets of doom flourished; the English language in America was going to disappear. “Their language will become as independent of England, as they themselves are,” wrote Jonathan Boucher, an English clergyman living in Maryland. Frances Trollope, mother of the novelist Anthony Trollope, was disgusted by “strange uncouth phrases and pronunciation” when she travelled in America in 1832. “Here then is the ruination of our classic English tongue,” mourned the British engineer, John Mactaggart. Even Thomas Jefferson found himself on the receiving end of an avalanche of British mockery, as The London Magazine in 1787 raged against his propensity to coin Americanisms: “For shame, Mr. Jefferson. Why, after trampling upon the honour of our country, and representing it as little better than a land of barbarism – why, we say, perpetually trample also upon the very grammar of our language? … Freely, good sir, will we forgive all your attacks, impotent as they are illiberal, upon our national character; but for the future, spare – O spare, we beseech you, our mother-tongue!”

But such protests did not stop Americans from telling the British to mind their own business, as they continued to use the language the way they felt they needed to in building their nation.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

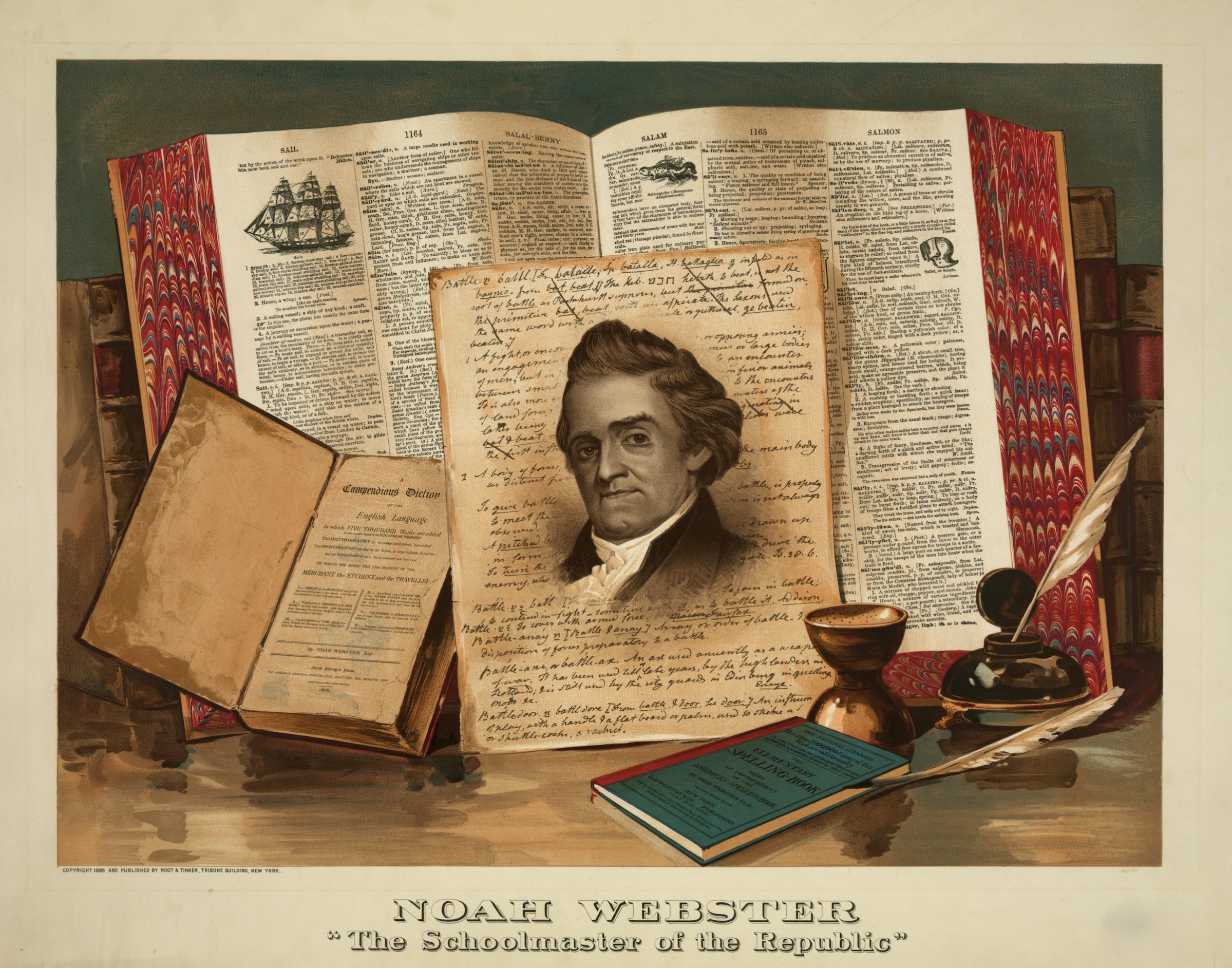

Independence, it was felt by many, was a cultural as well as political matter that could never be complete without Americans taking pride in their own language. On the part of the more zealous American patriots like Thomas Jefferson and Noah Webster, the goal was national unity fostered by a conviction that Americans now ought to own and possess their own language. Jefferson led the charge by declaring war against Samuel Johnson’s famous Dictionary of the English Language, which continued to reign supreme for a century after its publication in 1755. Unless Johnson were toppled from his perch as the sage of the English language, he argued, America could remain hostage to British English deep into the 19th century. Webster, the self-styled grammarian who egotistically claimed for himself the role of “prophet of language to the American people,” was by far the most hostile to British interference in the development of the American language. He wrote an essay entitled, “English Corruption of the American Language,” casting Johnson as “the insidious Delilah by which the Samsons of our country are shorn of their locks.”

“Great Britain, whose children we are,” he claimed, “and whose language we speak, should no longer be our standard; for the taste of her writers is already corrupted, and her language on the decline.”

Yet, not all Americans were on board with Webster’s ideas and many Americans fought back, thoroughly and lastingly mocking him for his egregious reforms of the language, especially spelling, as a way of banishing the persistent American subservience to British culture. Pointing to him, one of his many American enemies remarked, “I expect to encounter the displeasure of our American reformers, who think we ought to throw off our native tongue as one of the badges of English servitude, and establish a new tongue for ourselves. … the best scholars in our country treat such a scheme with derision.”

We have to give it to Webster that he did write, as he made a point of putting it in his title, the first comprehensive unabridged “American” dictionary of the language. That effort, such as it was, 30 years in the making, brought on the golden age of American dictionaries — that is, those written in the U.S. The great historical irony, in light of decades of British ridicule of what Americans were doing with the language, is that Americans, like Webster’s superior and forgotten lexicographical rival Joseph Emerson Worcester, quickly surpassed British writers of dictionaries and continued to do so for more than half a century, until the birth of the monumental Oxford English Dictionary finally began to replace Johnson’s as Britain’s national dictionary.

Nonetheless, the flow of bad blood shed throughout the tortuous language and dictionary wars in the 19th century continued well into the 20th century, confirming that America and Britain were then and still are, as is often said, two nations “divided by a common language.” Divided, indeed, as with the same language they have always been able to understand their insults of one another.

Peter Martin is the author of the book The Dictionary Wars: The American Fight over the English Language (Princeton University Press 2019). He is also the author of the biographies Samuel Johnson and A Life of James Boswell. He has taught English literature in the United States and England.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com