With its modernist buildings, spacious grounds and airy cafeteria packed with young adults slinging backpacks while scrolling through their Instagram feeds, the African Leadership University on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius looks much like any other college campus. Except, perhaps, when it comes to the library. Here you will find no silent temple to books and knowledge; in fact, the university’s Pure Learning Library has no books at all. Instead there’s a cacophonous din of competing ideas, as students convene in animated groups around communal tables, shouting out solutions while feverishly diagramming them on the whiteboards that panel the walls. “We aren’t really encouraged to be quiet here,” explains Jeremiah Nnadi, a second year Computer Science student from Nigeria, with a shrug. “We believe that the best way to learn is from our colleagues. Regurgitating the stuff you memorized from books just to pass an exam isn’t really going to solve Africa’s problems, is it?”

While books can be found elsewhere on campus, ALU’s approach to educating the next generation of African leaders looks a lot different from the traditional Western universities it was once modeled upon, starting with the scope of its ambition. When the Ghana-born, Stanford Business School-educated entrepreneur Fred Swaniker opened the Mauritius campus in 2015, he not only pledged to build 25 more like it in Africa, he also promised to produce 3 million young African leaders over the next 50 years. The first class of those leaders, made up 79 people hailing from more than 40 countries across the continent, graduate on June 12.

For Swaniker, this graduation serves as the first milestone in an ambitious program to reinvent education for a new generation in a uniquely African context. It is also the solution to an unanticipated problem that sprung up when he first sought to disrupt African education. In 2008, Swaniker launched his African Leadership Academy in Johannesburg, recruiting high school students from across the continent and promising to prepare them for the best universities the world had to offer. But once they got into those Ivy League and European universities, they rarely came back. “I realized we were actually contributing to the brain drain,” says Swaniker. “So I said it’s time that Africa had its own Stanford and MIT and Harvard. But instead of replicating the universities that were built for another era, we should build a university that looks to the future, that educates the leaders Africa needs.”

The Mauritius campus, with a residential program catering to 355 students, focuses on collaborative learning and pan-African leadership examples. Each classroom is dedicated to a influential African leader or artist — the Sankore wing, referencing one of the oldest universities in the world, in Timbuktu, Mali, features classrooms named after Ethiopian runner Haile Gebrselassie, U.N. general-secretary Boutros Boutros-Ghali and South African writer Bessie Head; the faculty lounge celebrates South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko. The four dormitories are dedicated to the great African civilizations, such as Axum, Kongo, and Songhai. Even the cafeteria aspires to pan-African cuisine, though Nnadi, the Nigerian computer-science student, says the attempt to create his nation’s national dish, jollof rice, “needs a lot of help.”

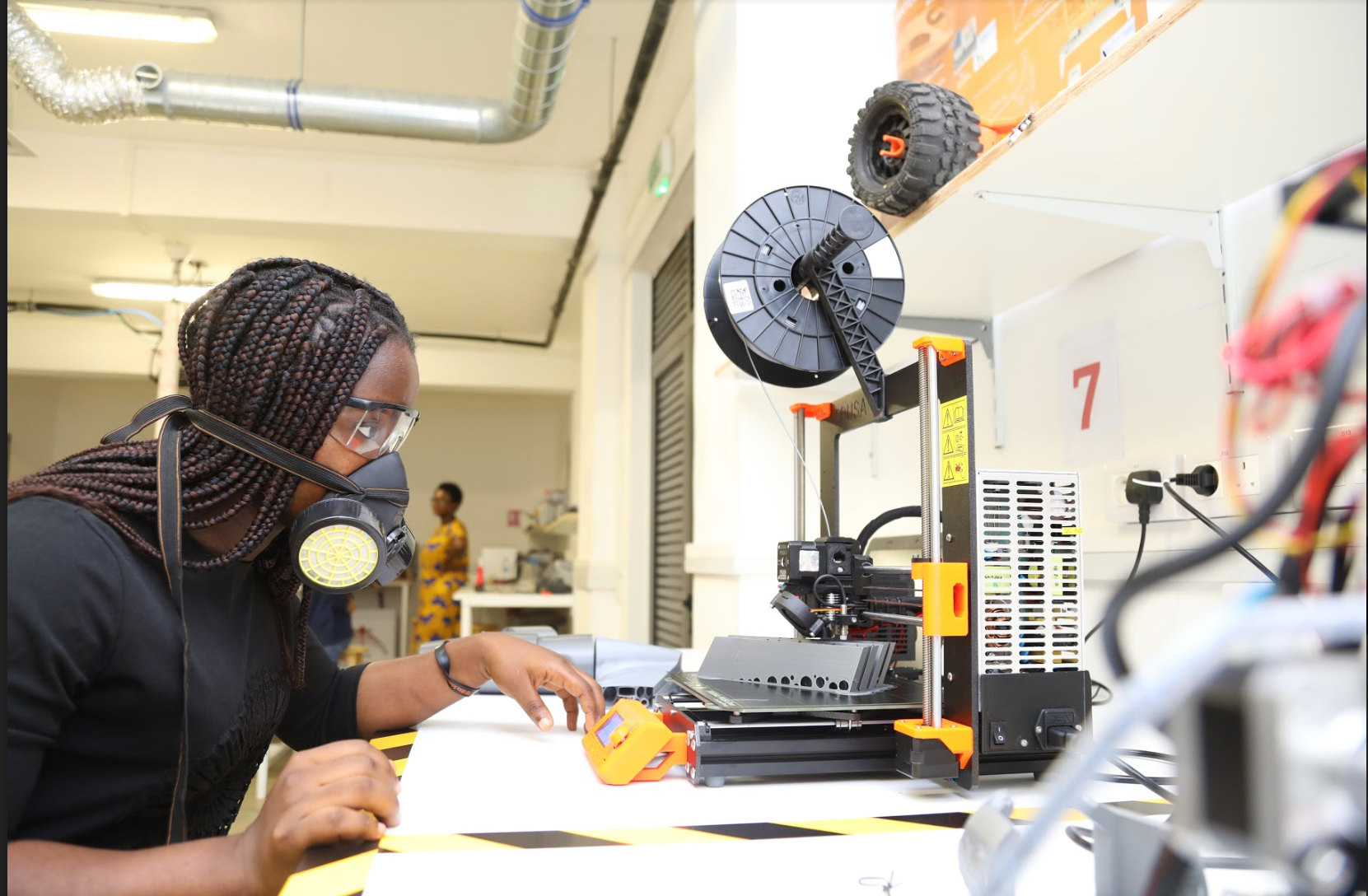

Complaints about cafeteria food being a universal college constant, the real difference at ALU can be found in the classrooms. ALU emphasizes real-world problem solving, starting on day one. Incoming students are presented with a list of challenges currently facing African countries, from climate change to health care, education, urban growth or immigration. For the rest of the year they are expected to research the issue, discuss it with classmates, teachers and outside specialists, and present concrete solutions. Developing leaders for the 21st century, says Swaniker, goes beyond academics. “The whole idea is to create problem solvers who have learned how to learn, rather than regurgitate knowledge. That means developing vital skills: critical thinking, leadership, communication, entrepreneurship, data analysis—this is what we need to develop Africa.”

Instead of majors, students have missions. Last year, one student established—and found funding for—a shelter for the island’s street dogs. Another team developed a campus-to-town transport system, vital for co-eds itching to get away from the sugar-cane fields surrounding the university for something more lively. Group work is encouraged because it develops leadership skills, says Nnadi, 20. “Going into real life from this point, I feel like there is no problem I won’t be able to deal with because I have seen it all: slackers, fights, conflict.”

And summer internships are mandatory. The school coaches students through the rigorous internship research and application process; by the time they graduate, most will have at least a year’s worth of work experience in Africa, and have applied to multiple jobs, giving them a head start in the real world. Nnadi has two internships lined up this summer—one at the Bank of Kigali in Rwanda developing an online platform for mobile banking, and another back home in Nigeria, mostly, he admits, so he can fill up on jollof rice before starting another school year.

The laser focus on problem solving means that graduates should be well prepared to tackle whatever comes their way, from finding a job to taking on some of the continent’s biggest issues. But the ALU experience has also raised the bar, making it harder for some students, like 25-year-old Kaone Tlagae from Botswana, to go back home. “I left home with the idea that I would come back and create change, but now that I have seen what the other countries [in Africa] have to offer, the other opportunities out there, I’m not sure it’s the right place for me anymore.” Maybe, she admits with a twinge of guilt as she contemplates taking a job in Kenya instead, ALU isn’t so good at stopping the brain drain after all.

Swaniker disagrees. The point of ALU, he says, is to create a cadre of African leaders and entrepreneurs who are trained to solve African problems, not just local ones. “We want a generation of Africans who are thinking on a continent-wide scale, who have networks across the continent, who can build pan-African businesses and grow economies and drive trade.” It’s not a brain drain, he says, but cross-pollination. “If someone from Botswana wants to develop a project in Zimbabwe, then there is probably someone from Zimbabwe who sees opportunity in Botswana.” A major part of entrepreneurship, after all, is spotting opportunities others might have missed.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com