By the late 1950s, having fired the first shot in the space war, Soviet President Nikita Khrushchev extended the competition with the West to everyday culture and lifestyle. Thus, in the summer of 1959 the Cold War moved to the field of cultural exchange. The Soviets organized an exhibition of their scientific, technological, and cultural achievements in New York, and the Americans followed with their own national exhibition in Moscow. Both Russians and Americans tried to show off their best clothes on each occasion. The official repositioning of the phenomenon of fashion in socialism therefore took place within the context of a fight for cultural supremacy.

American vice president Richard Nixon and his wife, Pat, traveled to Moscow to open the American National Exhibition. Before their visit, Pat Nixon carefully chose a new wardrobe, as reported in Newsweek:

One suit of natural raw silk, a brown silk taffeta cocktail dress, a silk and cotton flowered print dress with jacket and two other dresses. Most of her clothes were bought at Henry Bendel’s in New York where Pat spent an hour—and several hundred dollars. “They are costumes,” she explained. “Mostly full-skirted dresses with matching accessories to make a ‘picture.’ They are not high fashion and they’re the sort of thing I like, and which I think looks best on me.”

At the opening of the exhibition, in the company of her husband and the Soviet deputy prime minister Frol Kozlov, Pat Nixon glowed in her natural raw silk suit and smart hat. She looked just as she was supposed to: like a sophisticated and well-heeled American housewife. The message was clear: the Russians might be ahead in space research and education, but they cannot match the sophistication of Western dress and the easy smoothness of an American lady going about her everyday life.

Pat Nixon’s carefully chosen wardrobe revealed a lifestyle with which the Russians could not compete. This lifestyle was even recited by IBM’s RAMAC, the first commercial computer, present at the exhibition, which provided four thousand answers about different aspects of life in America. One of them offered information in perfect Russian about the wardrobe of an average American woman. She owned: “Winter coat, spring coat, raincoat, five house dresses, four afternoon ‘dressy’ dresses, three suits, three skirts, six blouses, two petticoats, five nightgowns, eight panties, five brassières, two corsets, two robes, six pairs of nylon stockings, two pairs of sports socks, three pairs of dress gloves, three pairs of play shorts, one pair of slacks, one play suit, and accessories.”

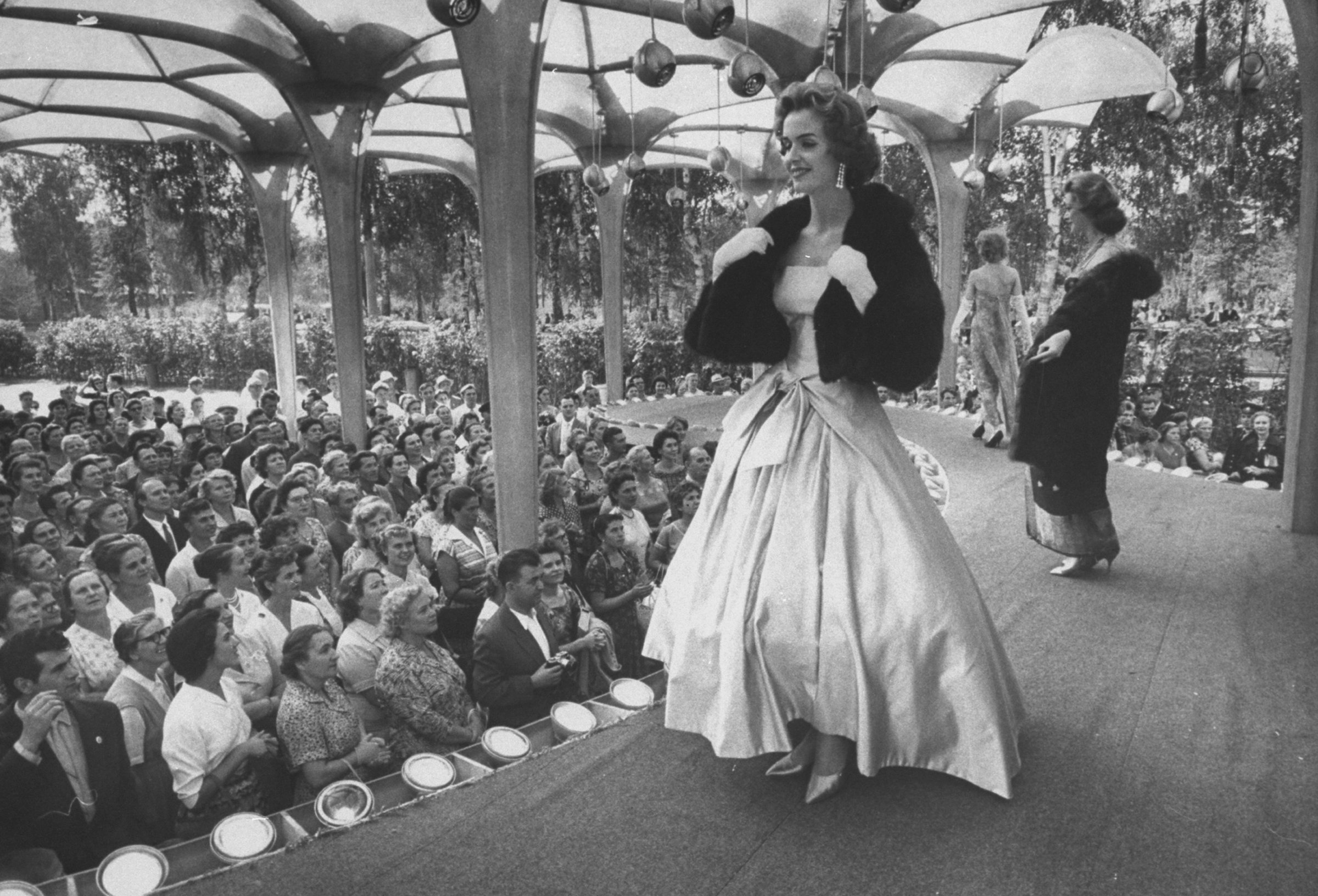

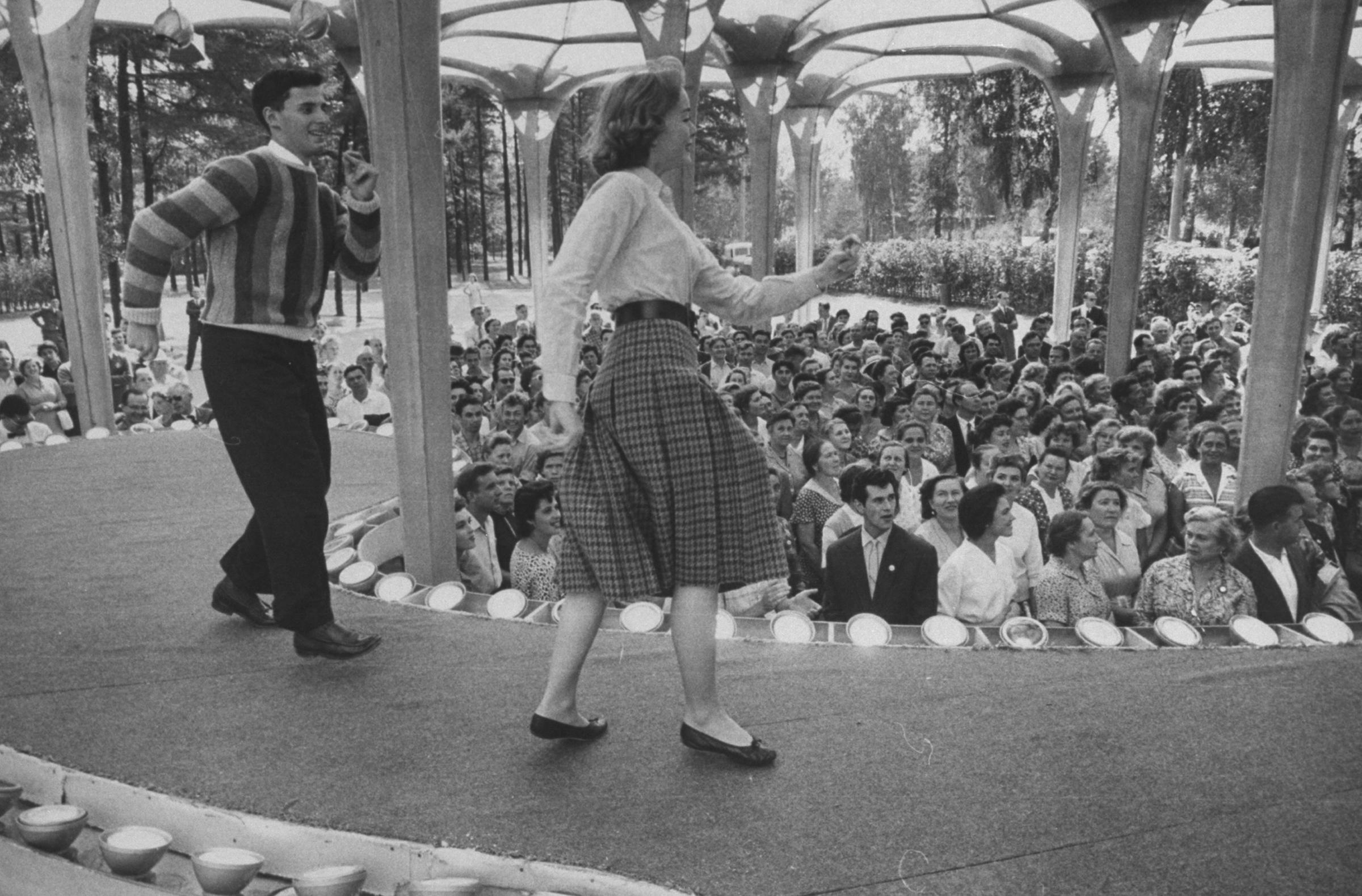

During the exhibition, American fashion was presented at four thirty-five-minute-long fashion shows that took place each day, each of them attended by three thousand to five thousand Russians. The Soviet authorities had opposed many of the American proposals for the exhibition, but eventually the Russian audiences got a chance to enjoy the American fashion shows, which consisted of youthful clothes, leisure wear, daily ensembles, and formal long evening dresses.

Attempting to bring the Russians “a living slice of America,” the outfits were presented by professional models as well as children, teenagers, grandparents, and whole families. Newsweek described the fashion show as boring, but acknowledged the political meaning behind the clothes: “The dresses were all right, though a bit on the dull side,” they reported. “The whole idea behind it was to show the people of the Soviet Union how the average American woman dresses at work and at play — not the glamorous girl on Park Avenue, but the young matron on Main Street.” The choice of everyday mass-produced American clothes was very powerful propaganda. If sophisticated outfits from New York fashion salons had been shown, they could easily have been attacked as elitist clothes meant for the exploiting class. But the Americans knew only too well that the Russians could not compete in the field of decent mass-produced clothing.

While fashion contributed to the huge propaganda effect that the American National Exhibition had in Moscow, the American media commented on the shortcomings in the culture of everyday Soviet life at the Russian exchange exhibition that had taken place only two months earlier in the New York Coliseum. “The Soviet exhibition strives for an image of abundance with an apartment that few Russians enjoy,” reported the New York Times, “with clothes and furs that are rarely seen on Moscow streets.” The fashion show that was included in the exhibition drew ironic comments from Western journalists. Five female models and one male model displayed designs by Soviet fashion designers from the leading Moscow department store GUM and the Dom modelei, or House of Prototypes, an institution created by Stalin to produce prototypes for socialist fashion. TIME magazine reported that “the textiles, mostly thick, heavy-textured woolen suits, are more impressive for their usefulness against the Russian winter than for their styles, which are clumsy attempts to copy western designs.”

Though the American media declared GUM’s outfits “clumsy copies,” they were actually the most prestigious representations of Soviet-style elegance. In 1956, GUM’s general director, V. G. Kamenov, wrote a booklet describing in detail the services that the Soviet flagship department store offered. Fashion ateliers for custom-made clothes and special shops selling natural silk, artistically hand-painted silk, women’s hats, fur coats, and perfumes were supposed to present an idea of abundance and sophistication. In the illustrations accompanying the text, attentive sales personnel were shown offering customers these traditionally luxurious goods. One section of the booklet dealt with new sales techniques, while another praised the fashion salons within the store, which offered individual service in sumptuous surroundings.

The store’s interior, filled with dark carved wooden furniture, crystal chandeliers, and heavy velvet curtains, was similar to the Stalinist concept of palaces of consumption of the 1930s. The store continued an outdated, grandiose aesthetics that promoted the mythical Stalinist concept of luxury. But this Stalinist glorification of reality, which tried to remove all conflicting and erratic elements from everyday life, could not compete with ordinary life in the West. Thus, with the opening of the Soviet Union toward the West, the disjunction between the deprivation of everyday life and its ideal representation became blatantly obvious.

By the late 1950s, in comparison with the efficiency of the large American department stores and the diversity and quality of the mass-produced goods that they offered, GUM had become outdated and provincial, as direct contacts with the West painfully revealed. The cover of LIFE magazine from August 1959 showed that the fashion war was taking place even at the highest diplomatic level. Flanked by Mrs. Mikoian (on her left), Nina Khrushcheva (right), and Mrs. Kozlova (far right), Pat Nixon appeared as a smartly dressed upper-class American housewife. The LIFE magazine cover was a visual testament to the Soviet diplomats’ wives’ inability to match the sophisticated, worldly style of Pat Nixon in her silk, flower-printed dress, a string of pearls, and carefully applied makeup, as well as her svelte figure. Accompanying their husbands, the ladies attended a dinner table conference at Khrushchev’s dacha, or country house.

There were significant visual differences among the three Soviet politicians’ wives, which pointed to their different levels of sartorial awareness. Nina Khrushcheva was clad in the simplest dress, which buttoned at the front. Called khalat, this style had become a domestic uniform of Soviet women. Women wore khalat at home, whether going about their domestic work, cooking, resting, or entertaining. Mrs. Mikoian was dressed in a sartorially more demanding outfit: a suit, with a cut that discreetly shaped the body. Her suit was modest, but its proletarian asceticism was softened with a little hat. That fashion detail showed a certain investment in her look, transforming her simple suit into an outdoor outfit.

The formal outfit worn by the wife of the Soviet deputy prime minister Frol Kozlov showed a full awareness of the importance of the occasion. Mrs. Kozlova’s evening gown, embellished with embroidery around the neckline, as well as her embroidered muslin stole, her white evening handbag, her white gloves, her hairstyle and makeup showed a new attitude toward fashionable dress. But Mrs. Kozlova could not yet match the sophistication of Western dress and the easy smoothness of an American lady of the same social standing. The ideologically informed rejection of fashion’s history was imprinted on Mrs. Kozlova’s dress even more so than on Mrs. Mikoian’s simple suit or Nina Khrushcheva’s symbolically burdened housedress.

Mrs. Kozlova’s appearance not only acknowledged contemporary formal Western dress, but it broke an important socialist dress code. The most important members of the political bureaucracy or nomenklatura had always dressed modestly in public, a practice that had started with the Bolsheviks. Stalin and his political circle had also stuck to the proletarian ideal of modesty in their public looks, although their private lives had been loaded with all the symbols of traditional luxury, from fur coats to house help, antique furniture, and fine food. The Old Bolshevik wives Nina Khrushcheva and Mrs. Mikoian respected the longstanding nomenklatura dress code. Recognizing that times were changing, Mrs. Kozlova, however, dared to transgress it.

This article is adapted from Djurdja Bartlett’s book FashionEast: The Spectre that Haunted Socialism, a richly illustrated study of fashion under socialism. Djurdja Bartlett is Reader in Histories and Cultures of Fashion at the London College of Fashion, University of the Arts London. This article originally appeared on the MIT Press Reader.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com