This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. A version of the article below was originally published at HNN.

On Dec. 8, 1859, to forestall a Haitian attempt to take possession of Navassa, a Caribbean island south of Cuba, U.S. Secretary of State Lewis Cass made a momentous decision. He officially recognized an American ship captain’s claim filed under the Guano Islands Act of 1856.

The law allowed American citizens to claim and possess islands “not within the lawful jurisdiction of any other government” for the purpose of mining guano (accumulated excrement of seabirds, valuable as agricultural fertilizer). In such an instance, “said island, rock, or key may, at the discretion of the President of the United States, be considered as appertaining to the United States.”

In his 1956 book Advance Agents of American Destiny, diplomatic historian Roy F. Nichols noted, “In this humble fashion, the American nation took its first step into the path of imperialism; Navassa, a guano island, was the first noncontiguous territory to be announced formally as attached to the republic.” None have been under U.S. administration for a longer time.

Cass’s decision ignored the fact that for more than two centuries Haitian fishermen had landed at the island to harvest shellfish. It also ran counter to every Haitian constitution since 1801, which had declared Haiti’s sovereignty over all its coastal islands including Navassa.

However, since the United States did not recognize the government of Haiti in 1859, these facts on the ground were considered of little consequence. Of greater importance was the perceived existential threat Haiti’s history of successful slave insurrection and emancipation while a French colony posed to American slave owners and their representatives in Washington.

Haiti and U.S. Imperial Ambitions

While slaveholders worried that their slaves might revolt against them as the Saint-Domingue slaves had done in 1791, many American politicians and journalists advocated the conquest and annexation of all the Caribbean islands, especially Hispaniola, as the logical way to extend American imperial power.

For example, in 1850 James Gordon Bennett, editor of the New York Herald, the largest and most popular daily newspaper in America, had advocated a plan “to annex Hayti, before Cuba.” He wrote that a war in pursuit of that aim “would be a source of fun and amusement, ending in something good for the reduction of the island to the laws of order and civilization. . . . St. Domingo will be a State in a year, if our cabinet will but authorize white volunteers to make slaves of every negro they can catch when they reach Hayti.”

The Haitian government countered such threats by maneuvering diplomatically among the European powers who risked seeing their hold over their own Caribbean colonies weakened and lost if they failed to thwart American plots against Haiti. But when a Haitian naval delegation attempted to take control of Navassa, President James Buchanan ordered the U.S. Navy to send a warship to Haiti to restore the American guano operation. Haiti’s commercial agent protested, but the State Department dismissed his letters.

An adviser to Haitian President Faustin Soulouque wrote to him candidly, “Even though the law is on our side in this affair, justice and the legitimacy of our cause will triumph only when certain barriers in the United States are broken down. Even after those fall, we should not believe their promises until they no longer attach economic importance to Navassa.”

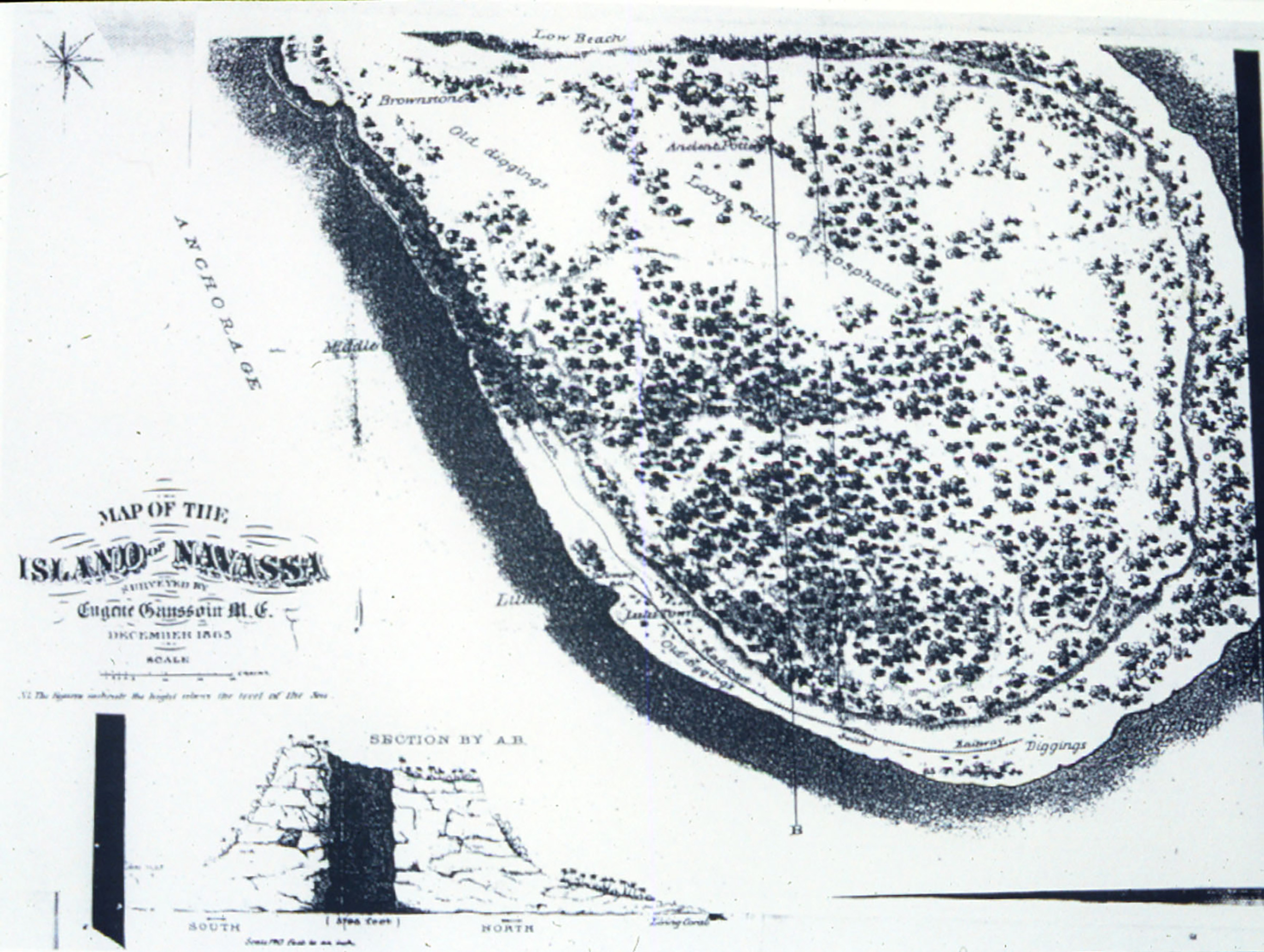

From 1857 to 1898, American companies based in Baltimore and New York mined and sold Navassa’s guano, employing black laborers supervised by white managers.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The 1889 Navassa Revolt and its consequences

On Sept. 14, 1889, African American workers at Navassa rose in revolt against their cruel white supervisors. By the time the battle ended, four whites lay dead. A fifth would die several days later.

Removed to Baltimore, 43 insurgents were charged with crimes ranging from rioting to murder. Two African-American organizations — the Brotherhood of Liberty and the Order of Galilean Fishermen — hired a legal team of three black and three white lawyers to defend them.

Tried in U.S. Circuit Court, three defendants were convicted of murder and sentenced to hang. Others were convicted of lesser crimes — 14 of manslaughter and 23 of rioting — and sentenced to prison terms. Three were acquitted. The executions were stayed pending an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court styled Jones v. U.S.

In that proceeding Jones’ lawyers challenged the constitutionality of the Guano Act, the authority of the United States government over Navassa and the jurisdiction of the American court. Among the issues was Haiti’s claim to the island. The high court rejected those arguments and affirmed the conviction.

In language that has freighted international relations ever since, the court declared on Nov. 24, 1890:

. . . if the executive, in his correspondence with the government of Hayti, has denied the jurisdiction which it claimed over Navassa, the fact must be taken and acted on by this court as thus asserted and maintained; it is not material to inquire, nor is it the province of the court to determine, whether the executive be right or wrong; it is enough to know that in the exercise of his constitutional functions he has decided the question.

Supporters of the defendants mounted a petition campaign, urging President Benjamin Harrison to grant the insurgents executive clemency. Harrison responded favorably. Citing the inhumane conditions imposed on Navassa workers, he wrote, “They were American citizens, under contracts to perform labor, upon specified terms, within American territory, removed from any opportunity to appeal to any court, or public officer, for redress of any injury, or the enforcement of any civil right.” He commuted the death sentences to life imprisonment.

Guano mining continued at Navassa for another eight years, “longer and more extensively than any other island, rock, or key that ever appertained to the United States,” according to Jimmy M. Skaggs, author of the 1994 book The Great Guano Rush.

Navassa Island in the 20th century

By the turn of the 20th century, Americans had abandoned Navassa to castaways, Haitian fishermen and nature. However, a new purpose revived Navassa’s importance. Anticipating substantially increased maritime traffic after the Panama Canal opening in 1914, some naval authorities feared that in stormy weather Navassa would become a dangerous hazard to navigation. In 1913 Congress authorized construction of a lighthouse on the island.

On Jan. 17, 1916, shortly before construction began, President Woodrow Wilson codified the island’s status as a site for a lighthouse and reaffirmed its status as a possession “under the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States and out of the jurisdiction of any other government.”

After World War I the Navy established a radio station at Navassa. In 1929 the lighthouse was automated. During World War II, the Coast Guard stationed a reconnaissance unit and a rescue launch there to defend against German submarines.

Navassa and its “appurtenance” apparition after World War II

The end of the war restored Navassa to its Wilsonian status as a lighthouse reserve, periodically serviced by the Coast Guard and visited by Haitian trespassers who paid no heed to the American Guano Act. But the heritage of the Guano Act and the Jones v. U.S. Supreme Court precedent continued to cast a long shadow beyond that single small island.

Less than a month after Japan’s surrender President Harry S. Truman proclaimed that “the Government of the United States regards the natural resources of the subsoil sea bed of the continental shelf beneath the high seas but contiguous to the coasts of the United States as appertaining to the United States, subject to its jurisdiction and control.”

As if to wring as much international mischief as possible from Truman’s proclamation, the April 1947 issue of Nation’s Business magazine published an article titled “A Legal Key to Davy Jones’ Locker” with the teaser subhead “A forgotten murder provides a background for our announced right to seek oil in the Gulf of Mexico.” Navassa as a metaphor for the unrestricted exercise of extraterritorial power had superseded the significance of the island itself.

Haitian hopes raised and dashed

Nine years later, Rep. William L. Dawson (R-IL) introduced “A bill to disclaim any rights of the United States to the island of Navassa,” which was referred to the Committee on Foreign Affairs in the House of Representatives.

Although the bill stood no chance of being reported out, intellectuals in Haiti seized the opportunity to reprise their country’s claim to Navassa. The cultural journal Optique devoted 28 pages of the August 1956 issue to the subject. An unsigned introductory article reviewed the history of the dispute, summarized Haiti’s legal position, and cited American attitudes both pro and con.

African Americans and advocates of a just and democratic foreign policy tended to sympathize with Haiti’s claim; the Eisenhower administration and career State Department diplomats ignored them. A monthly Coast Guard patrol continued to maintain the lighthouse. From time to time, beginning in 1956 and continuing to the present, U.S. amateur radio hobbyists have obtained permission to set up temporary broadcasting stations at Navassa.

Clandestine attack on Cuba from Navassa Island

“Cuban Outbreak of Swine Fever Linked to CIA” headlined a Jan. 9, 1977, article in Newsday, a Long Island, New York, daily paper. It began,

With at least the tacit backing of U.S. Central Intelligence Agency officials, operatives linked to anti-Castro terrorists introduced African swine fever virus into Cuba in 1971. Six weeks later an outbreak of the disease forced the slaughter of 500,000 pigs to prevent a nationwide animal epidemic.

A U.S. intelligence source told Newsday he was given the virus in a sealed, unmarked container at a U.S. Army base and CIA training ground in the Panama Canal Zone, with instructions to turn it over to the anti-Castro group.

The 1971 outbreak, the first and only time the disease has hit the Western Hemisphere, was labeled the “most alarming event” of 1971 by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization. . . .

Another man involved in the operation, a Cuban exile who asked not to be identified, said he was on the trawler where the virus was put aboard at a rendezvous point off Bocas del Toro, Panama. He said the trawler carried the virus to Navassa Island, a tiny, deserted, U.S.-owned island between Jamaica and Haiti. From there, after the trawler made a brief stopover, the container was taken to Cuba and given to other operatives on the southern coast near the U.S. Navy base at Guantanamo Bay in late March, according to the source on the trawler.

Six days later the CIA officially denied the story, which had been widely reprinted, but the Newsday reporters had cited so many corroborating sources, with such specific details, that the denial was not widely believed.

A previously unreported document lends circumstantial support to the Newsday story — a 1986 typescript draft of an article by U.S. Coast Guard lighthouse historian Neil Hurley titled “Navassa Island Light, ‘Where Chickens Only Miraculously Survive the Attacks of Lizards’.”

When Hurley’s article appeared in the Winter 1988 issue of The Keeper’s Log, under the title “Navassa Lighthouse,” these two sentences from his earlier draft were omitted: “In 1971, a U.S. Navy Research team visited the Island to look for animal diseases that could be transmitted to man. They found one bird carrying malaria.”

It might be a coincidence, but it seems remarkable that the Navy was investigating the possible presence of biological toxins at about the time that agents were reported to have brought dangerous microbes to Navassa for a biological attack on Cuba.

What made the Newsday report credible was the fact that the only place in the Western Hemisphere where the virus was known to have been kept before the Cuban outbreak was the secret Plum Island laboratory off the eastern tip of Long Island. (Newsday reporters had been cultivating sources there since the paper’s sole visit in October 1971.)

The Newsday article made no mention of Plum Island, perhaps to protect its reporters’ sources, but other writers quickly made the connection. In his 2004 book about Plum Island, Lab 257, Michael Christopher Carroll wrote that although “no one will say on the record that the virus for the Cuban mission was prepared on Plum Island,” that was almost certainly its source. “Efforts to explain away the outbreak as a natural occurrence do not hold up to close examination.”

What lies ahead for Navassa Island?

Haiti has never relinquished its claim to Navassa, and its citizens have continued to flout U.S. authority. Following the example set by their North American peers, in the spring of 1981 members of the Radio Club d’Haiti were issued the call sign HH0N and flown to the island by helicopter.

Upon arrival they raised the Haitian flag and sang their national anthem. When an American military officer asked to see their authorization to land, they answered, “We need no permit to travel in our country.” The officer relented and welcomed the Haitians to camp. After a seven-day stay, they returned the way they had come.

Today the Fish and Wildlife Service of the Interior Department administers the island as a national wildlife refuge. News reports of a 1998 scientific expedition called Navassa “a unique preserve of Caribbean biodiversity” but paid scant attention to Haiti’s claim, or to the heartless history that awaits atonement. We can take the first step along that path by teaching it.

Ken Lawrence founded the Deep South People’s History Project in 1973. Today he studies, collects, and writes about aviation history, air transport, and air mail, which are occasional subjects of his monthly columns in Linn’s Stamp News.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com