President Richard Nixon promised Americans that the Paris Peace Accords ending the Vietnam War would bring “peace with honor.” They brought neither, and it now appears that the Afghan War is headed for a similar denouement.

The Paris Accords required the United States to withdraw its military forces from South Vietnam within sixty days, but allowed North Vietnam to keep 100,000 troops on South Vietnamese soil. The reported “outline” of an agreement discussed by American and Taliban negotiators in Qatar in January requires the United States to withdraw its remaining 14,000 military personnel from Afghanistan, while leaving the Taliban in control of over 50% of the country. In exchange for the U.S. military leaving South Vietnam, the Communists freed 591 American POWs; in exchange for an American troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Taliban is promising to prevent terrorist organizations from using the country as a base of operations—a pledge as unenforceable as North Vietnam’s pledge to participate in “free and democratic elections.”

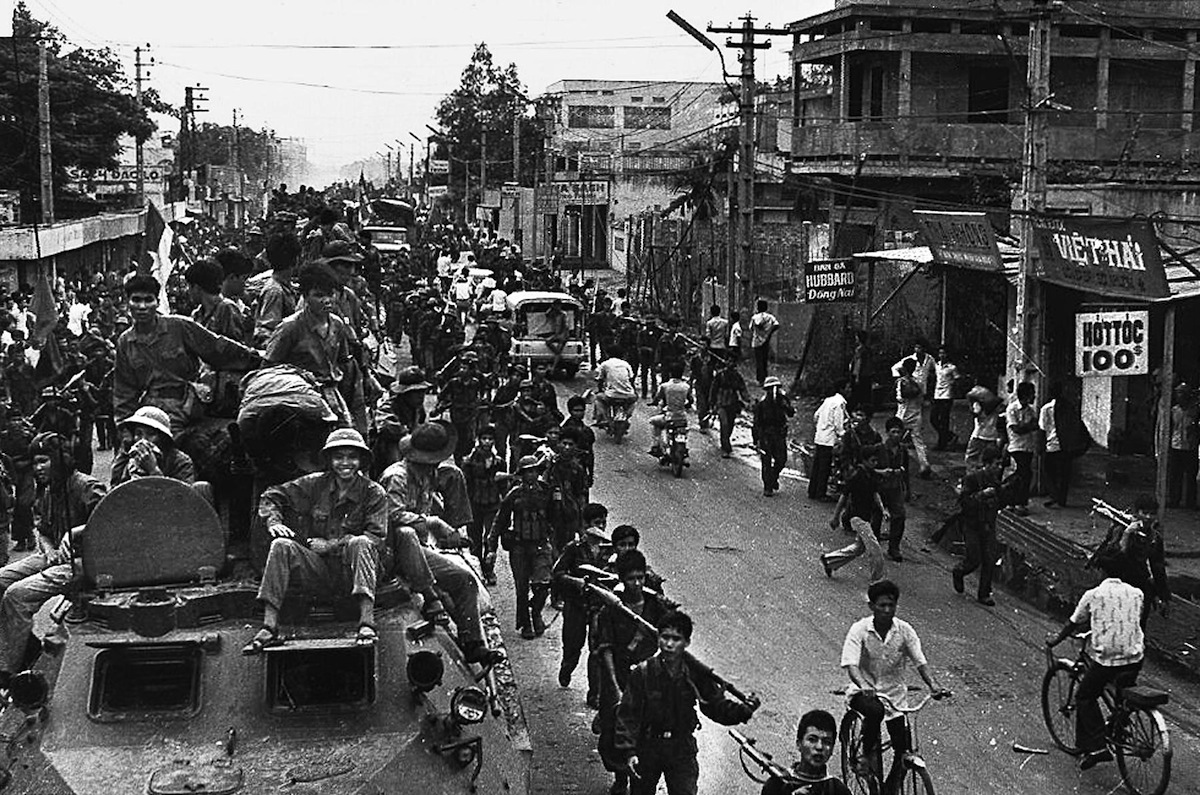

South Vietnam experienced a two-year “decent interval” between the signing of the Accords and the fall of Saigon. During Afghanistan’s decent interval the Taliban are certain to gain more power in whatever coalition government follows a peace agreement. Tanks will not crash through the gates to the Presidential Palace in Kabul, as they did in Saigon, because by then the Taliban may control the palace. But as was the case in South Vietnam, the fall of Kabul will likely create hundreds of thousands of desperate refugees. These will include Afghans who fear for their lives because of their associations with the U.S. and former Afghan governments and military, and Afghans who are as unwilling to live in a radical Islamic state as many South Vietnamese were to live in a communist one.

Although the Vietnam War did not have an honorable end, some Americans risked their lives and careers in the cause of an honorable exit. During April of 1975 U.S. armed forces helped evacuate 130,000 South Vietnamese, collecting them at sea or flying them out of Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut airport to makeshift refugee camps at U.S. bases in the Philippines and Guam before transferring them to relocation camps in America. It amounted to the largest emergency humanitarian operation in our history, and it happened because American military personnel, government employees, and private citizens in Saigon and Washington staged a spontaneous mutiny against the inaction of senior U.S. officials, and the callousness of a majority of Americans and their elected representatives. They believed that a nation built by immigrants had room for more, and that they had a moral duty to evacuate their Vietnamese allies, saving them from years of imprisonment in a Communist gulag, or a bloodbath like the one underway in neighboring Cambodia. And so they cobbled together underground railroads of safe houses, black flights, disguises, and fake flag vehicles, smuggled Vietnamese friends, co-workers, and strangers into Tan Son Nhut airport in ambulances, metal shipping crates, and refrigerator trucks with air holes drilled in their floors, and signed affidavits swearing to be financially responsible for the thousands of adults they pretended to “adopt.’ President Ford finally bowed to his conscience, and to the necessity for a legal justification for accepting these evacuees, and directed his Attorney General Edward Levi to grant an emergency visa parole for 130,000 South Vietnamese. The parole covered “significant political and intelligence figures,” the relatives of American citizens, and past and current employees of the U.S. government in Vietnam who were considered at “high risk” of suffering retribution under a Communist regime.

Ford’s parole was courageous. The United States was suffering from a recession, inflation, and an 8.7% unemployment rate. There was prejudice against Vietnamese. Polls showed 54% of Americans saying they would not “welcome” Vietnamese refugees, and two thirds opposed to sending more military aid for Cambodia and South Vietnam even if it would “spare the populations of those countries a bloodbath.” Governor Jerry Brown came out against settling Vietnamese in California, declaring, “We can’t be looking 5000 miles away and at the same time neglecting people who are living here.” Letters opposing Vietnamese refugees flooded Congress. Senator George McGovern, who had run for president in 1972 on an anti-war platform, insisted that “Ninety percent of the Vietnamese refugees would be better off going back to their own land,” and suggested that Congress pass a program facilitating “their early return to South Vietnam.”

The hostility to the refugees reportedly left President Ford “disappointed and very upset.” He said it did not reflect “the America I know,” remarking later, “I took them out because they would have been killed, and I’m glad of it.” His leadership helped shift public opinion. Americans began listening to their better angels and inundated the White House and State Department with offers to provide the refugees with homes, jobs, and financial assistance. By December 1975 the resettlement camps had emptied and most of the 130,000 Vietnamese were on track to become American citizens.

One day before Saigon fell Lieutenant Colonel Harry Summers climbed onto the roof of a soft drink stand in the U.S. embassy compound with a bullhorn and shouted to the several thousand Vietnamese who had taken refuge there, “Every one of you folks is going to get out of here. Let me repeat that: all of you people here with us today are going to be flown to safety and freedom.” A journalist witnessing Summers’ performance wrote that he had “taken it upon himself to sweep up some of the dust of America’s honor in Vietnam.” That afternoon, Colonel Al Gray, who commanded the Marine ground security force protecting the evacuation from Tan Son Nhut, told his men, “We’re not going to play God. We’re going to take out everyone who wants to go.” When a journalist asked White House Press Secretary Ron Nessen to cite a legal rationale for evacuating South Vietnamese on U.S. military helicopters he shot back, “I am citing a moral rationale.”

It seems inconceivable now that the United States would evacuate 130,000 Afghans in a month and resettle them in the United States within a year. The fear of terrorism since September 11, 2001 is no doubt partly responsible for the hardening of some American hearts toward refugees. But there is also a generational explanation for why welcoming refugees has become a less integral part of our national DNA, for why the United States admitted 207,000 refugees in 1980, a record high, but in 2018 admitted only 22,000, a record low. In 1975, Americans had already spent three decades welcoming post-World War Two refugees from Europe, and Cold War refugees from Hungary and Cuba. In 1975, the Immigration Act of 1965 that would open immigration to citizens of third world countries had not yet transformed America’s racial complexion, engendering fear and resentment among some Americans.

So who will now sweep up the dust of our honor in Afghanistan? Run underground railways to Bagram Air Base? Cite a “moral rationale’ for evacuating tens of thousands of Afghans? Say that abandoning our former allies to the mercies of the Taliban does not reflect the America they know? The answers to these questions may come sooner than we might like.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com