On May 30, 1868, Gen. John A. Logan visited Arlington National Cemetery to speak at a ceremony for what was then called Decoration Day — and in doing so, set a precedent that holds to this day.

That event, organized three years after the end of the Civil War by the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the major Union veterans association that he ran, is considered the first national Memorial Day celebration ever to be held at Arlington National Cemetery.

“Cherishing tenderly the memory of our heroic dead,” Logan said, “who made their breasts a barricade between our country and its foes… We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance.”

He picked that day for the event thinking that by then, the “choicest flowers of springtime” would have bloomed, and could be used to decorate the graves of those who died fighting what is still America’s deadliest war.

But though the connection between the history of Memorial Day and Arlington National Cemetery runs deep, the creation of the burial space wasn’t carefully planned. Rather, it was an act of desperation as the Civil War death toll mounted.

“It wasn’t by design. It was a need of a moment and the moment was the Civil War,” says Robert M. Poole, author of On Hallowed Ground: The Story of Arlington National Cemetery. The Civil War lasted longer than expected and brought more fatalities than expected — more than the federal government could handle. Many of the wounded Union and Confederate soldiers were brought to Washington, D.C., for treatment, and many died there. “The location [of the cemetery] was considered a practical matter,” Poole says. “A lot of the fighting took place close to Washington D.C., and all of the cemeteries in the D.C. area filled up.”

In 1864, thousands died in the so-called “40-Days Campaign” in Virginia. The Quartermaster General of the Union Army, Montgomery C. Meigs, is considered the father of Arlington National Cemetery because he came up with the idea to bury these men on the plantation where Confederate General Robert E. Lee had lived until the Civil War broke out and his family fled.

The first burial there took place on May 13, 1864, for Private William Christman of Pennsylvania, who died of peritonitis, an infection he developed when he contracted the German measles. “No one knows why but it’s probably because he was a farm boy who he didn’t have the immunities that a lot of the city boys had,” says Poole. “He never saw a day of battle, but he’s one of the many Civil War soldiers who died, not in direct combat, but from disease — smallpox, measles, yellow fever, infection from wounds.”

The placement of some of the first graves was initially a dig at the Confederates, as the war was still in full force.

“There were Union officers living in Lee’s mansion at the center of the plantation, and they didn’t want to see gravestones out the window everyday, so they put Christman as far away as possible,” says Poole. Meigs and Lee had once to be Army buddies, before the war, but now Meigs considered his old friend a traitor who deserved to be punished. “Meigs thought it was poetic justice to take this land and make it a cemetery. When he found out Christman was buried away from the mansion, he said, ‘To hell with that! I want the burials right by the house so if the war ends, and the Lees come back, they wont be able to live there.’ So the casualties started being buried right by the house in Mrs. Lee’s garden, where they remain today.”

A few weeks later, on June 15 of that year, Arlington National Cemetery was officially established when the War Department carved out 200 acres of the plantation for the purpose.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In the decades following the war, among many other national reconciliation efforts, efforts were made to unite the two sides at Arlington National Cemetery. In 1901, the remains of Confederate soldiers who had initially been buried with Union soldiers were re-interred in a special Confederate Memorial section. But that’s not the only way in which who has been buried there has changed over time.

“During the Civil War, Arlington was almost a pauper’s cemetery,” says Poole. “If you walk through the oldest section of Arlington today and walk among the tombstones, it’s young men who couldn’t afford to be shipped home. It wasn’t until many years after the war, when we began to make sense of what had happened, that Union officers, including Meigs, began to be buried there, and it became a fashionable place to be remembered.”

In fact, Arlington became so respected that men killed in other wars were exhumed to properly honor them by re-burying them there. Today, more than 400,000 people are buried there, and the cemetery has grown from 200 acres to 624 acres; additional planned expansions could bring it up to 688 acres. Space has become an ongoing issue, especially since millions watched President John F. Kennedy’s funeral there live on television.

“That really put Arlington on the map,” says Poole. The number of visitors jumped from about 2 million to 7 million in one year, and restrictions for burial tightened.

Nowadays, those who are eligible for in-ground burials include most active duty military service and retired members of the Armed Forces who qualify to receive retirement pay — as well as their spouses and any children who are minors or dependent adult children — recipients of the Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross (Air Force or Navy), Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star or Purple Heart, and any former prisoner of war “whose service terminated honorably” and who died on or after Nov. 30, 1993. The eligibility requirements for above-ground inurnment are more flexible. The section for cremated remains has helped save space somewhat, but in 2018, the cemetery warned that at the current rate of 7,000 buried annually, it’s expected to reach capacity in 25 years.

And yet, no matter what rank or position in society they hold, no matter what war they served in, or what divides the country at any given moment in history, veterans buried there and the soldiers who bury them are united by a common bond, the shared experience of serving their country in the military.

That’s what Tom Cotton — a U.S. Senator (R-AR) and former platoon leader of what’s known as the Old Guard, the Army’s oldest active-duty infantry regiment and its official ceremonial unit — recalls one soldier telling him when he was researching his new book Sacred Duty: A Soldier’s Tour at Arlington National Cemetery: “Funerals at Arlington are the same, whether they’re for the President or a private. It’s the one place where all soldiers are laid to rest are given equal honor.”

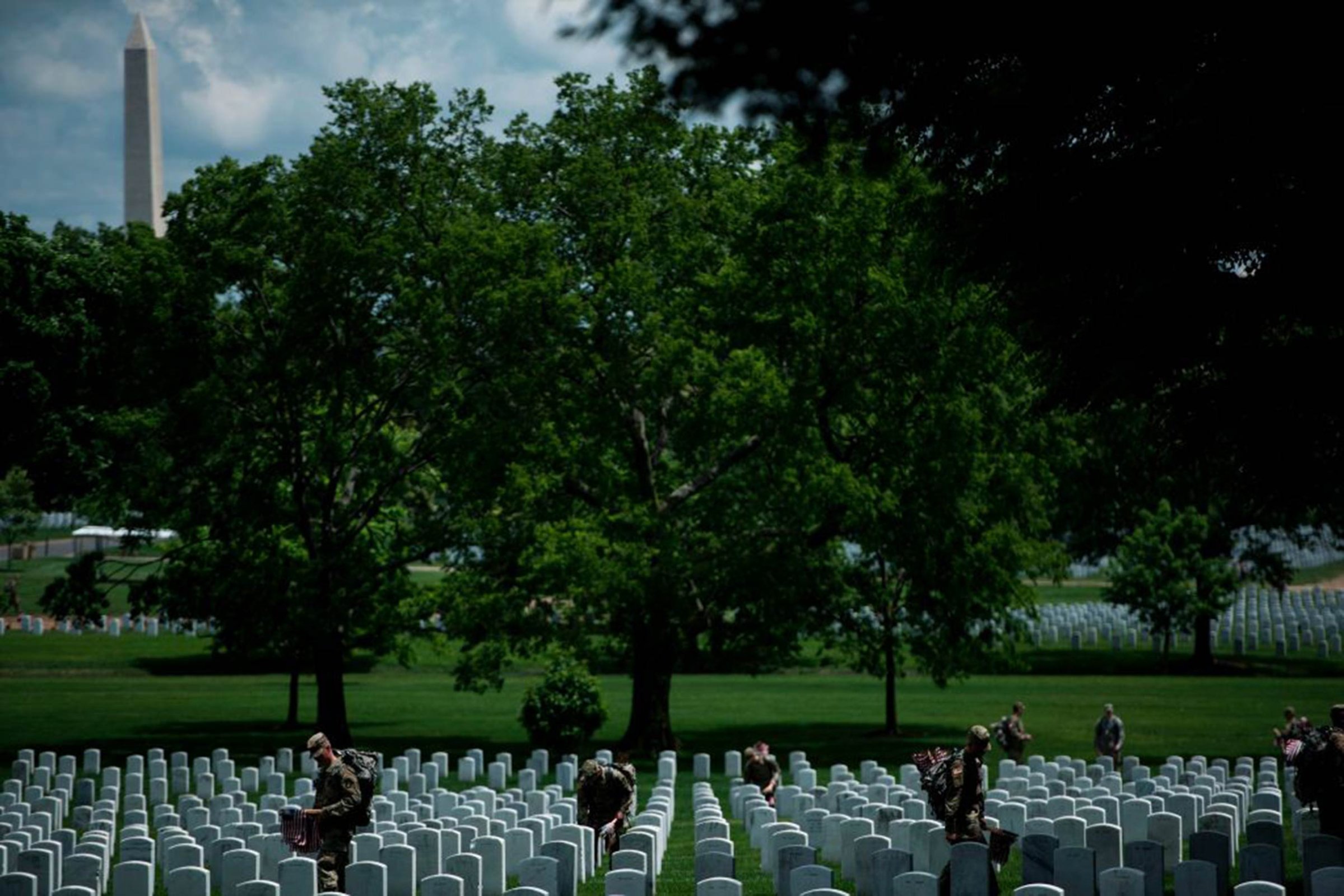

The Memorial Day ceremony held there annually, at an amphitheater that seats an estimated 5,000 people, is one of the biggest remembrance ceremonies that takes place at the cemetery. A band plays; this year it’s the United States Coast Guard Band. In the spirit of Logan’s vision to decorate every veteran’s grave with flowers, a group places roses at the headstones. There’s a full honor wreath laying ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. It’s customary for the President of the United States to give a speech. This year President Trump and First Lady Melania Trump visited ahead of the long weekend, because he’ll be in Japan on Memorial Day, and helped place miniature Americans flags at the headstones, a tradition that dates back to 1948. Every Thursday before the long weekend, The Old Guard soldiers, armed with backpacks of American flags, place a flag next to each of the more than 228,000 headstones on the grounds and at the bottom of about 7,000 rows of niches for cremated remains.

“The first time I did it, after about two rows, my hands were eaten up from pushing the flags into the ground, and I asked my young soldiers why they were moving so quickly, and they were astonished I didn’t have a bottle cap,” Cotton says. “You use a bottle cap to push the flags into the ground, one of those small tricks that gets passed down from soldier and soldier. Then the soldiers patrol the grounds over the weekend to make sure the flags are still there and replace any damaged ones, so every person who has a loved one at Arlington knows that a soldier has been by every gravesite to remember his or her service and sacrifice for the nation.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com