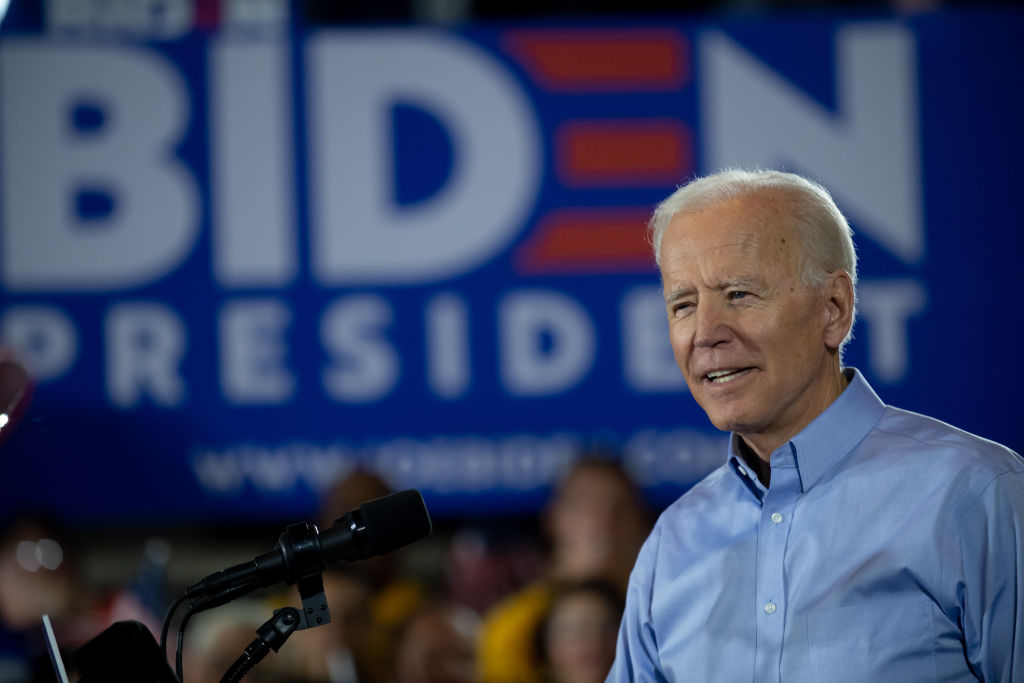

Since he joined the crowded field of Democratic presidential contenders, former Vice President Joe Biden has worn the mantle of frontrunner comfortably.

Polls show him ahead by double digits, nationally and in early nominating states. His campaign is stacked with pros. He’s raking in cash like an incumbent — $6.3 million in the first 24 hours — and spending a bunch of it. He even has an SUV rumbling, evoking his nine years with a Secret Service detail.

On Saturday, he’ll face his next test, as he officially kicks off his campaign in Philadelphia, where it will be based. Biden wants to make a splash, reserving the stretch of lawn between the art museum and city hall for a massive rally, one he hopes will be reminiscent of Barack Obama’s audiences.

To date, Biden’s campaign stops have been smaller in scale, typical of the retail politicking at this stage in the campaign cycle.

He made his candidacy official on April 25 with an online video and high-dollar fundraiser, then waited four days to make his first campaign stop, at a union hall in Pittsburgh. Since then he’s opted for backyards in Nashua, N.H., and coffee shops up the road in Concord.

Still, he’s drawing larger crowds at these events: almost 400 people in Hampton, N.H., and more than 500 in Manchester, N.H., earlier this week.

Some Biden advisers had wanted him to make the earlier announcement in Philadelphia, while others were aware of the risks involved if he failed to meet expectations. Still wary of failing to make a splash, aides refused to say how many have RSVP’ed for Saturday’s kickoff, pointing instead to watch parties taking place in homes and coffee shops for supporters farther afield.

In this, his third run for the Democratic presidential nomination, Biden is playing his cards carefully. He’s had a few missteps, such as referring to the British prime minister as Margaret Thatcher when he meant Theresa May. He’s faced difficult questions about how he behaves publicly around women and his treatment of Anita Hill during her testimony on Capital Hill in 1991.

But he’s also carefully responded to criticism from freshman Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez about his “middle-of-the-road” environmental agenda, avoiding a confrontation with a darling of the millennial left.

Biden knows the risks. He watched in horror in 2008 as Hillary Clinton supporters vowed to never support Barack Obama for president after a bruising nomination fight. And he saw the same dynamic again in 2016, when some Bernie Sanders’ supporters either stayed on the sidelines in the general election or opted for a third-party candidate, costing her crucial votes in states like Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin.

He hopes to avoid a similar split among Democrats in 2020, vowing not to attack fellow Democrats or speak ill of them. Part of the reason, advisers say, is that Biden desperately wants to face and defeat Trump next year. Biden is a competitive guy, advisers say, and is itching to tussle with Trump, whom he considers a bully and blowhard.

This is Biden’s last shot at a job he has wanted since he was first elected to the Senate in 1972, and he’s listening to his team about how best to get there. For instance, during the week that ended May 11, Biden’s team spent almost $240,000 on Facebook ads alone to try to build a political machine in short order. (Elizabeth Warren was the closest competitor, at more than $88,000 in Facebook ads. One pro-Trump super PAC, by comparison, spent about $64,000.)

Still, Biden’s position at the top of the pyramid also makes him a target. Other early frontrunners like Rudy Giuliani or Jeb Bush have weathered months of attacks that ultimately doomed their campaigns, and his rivals have already showed how sharp their jabs can be. Amid Democratic chatter that she would make a good running mate for Biden, California Sen. Kamala Harris flipped the script, telling reporters that he would make a great running mate for her, since he already knew how to be vice president.

Biden can expect similar treatment at the upcoming Democratic debates, where those farther back in the pack will need to differentiate themselves with carefully aimed shots.

Biden’s plan, after the Saturday spectacle, will be to give a number of policy-centered speeches about specific challenges facing the United States. He made his online announcement about the heart, arguing America’s core character was under assault by the incumbent President and suggesting the country needed to return to a time of more normal politics. Going forward, he’s looking voters’ heads with a policy platform that will borrow from the Obama era and layer on more progressive ideas on the environment and health care.

Biden advisers say he’ll never compete directly with the likes of candidates farther to the left like Sanders, who has proposed a government-run health insurance program with a price tag in the trillions. But he can tangle with the likes of Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, whom he personally likes, in a contest of ideas.

And through it all, he’ll be subtly making the case that he is best prepared to appeal to the white, working-class voters who swung the Midwest to Trump in 2016.

Many of Biden’s advisers, however, say they have studied Clinton’s campaign, which had hundreds of policy ideas that landed with a dud compared to the circus Trump created. They say they understand the challenges Trump brings to the race but also cannot ignore what should be the reason to run, which is to govern a country at the end of the campaign.

First, though, you have to capture voters’ imaginations, which is why Biden is set to blare some Bruce Springsteen on Saturday as he launches his campaign not far from the art museum steps made famous in the first “Rocky” movie.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com