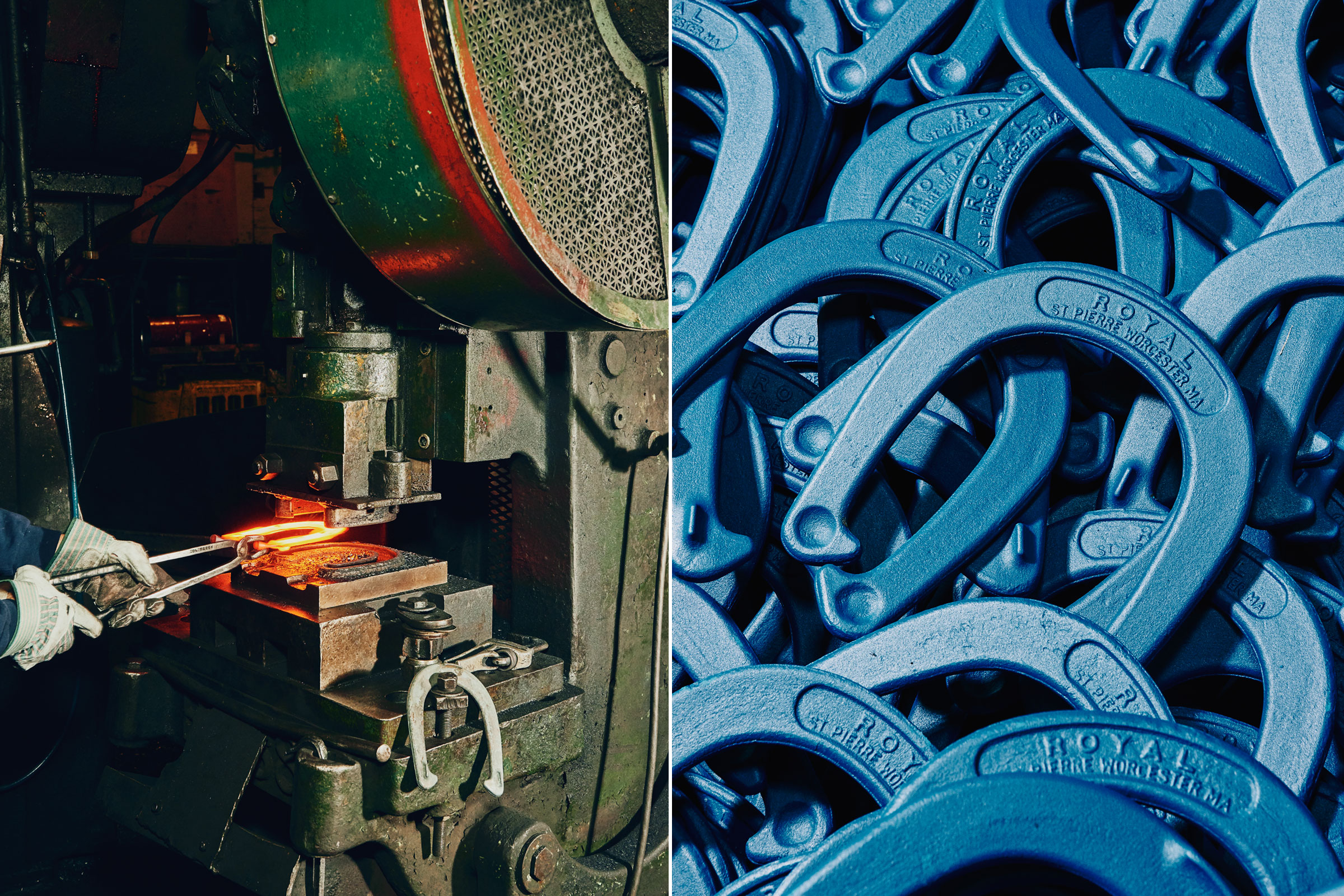

For nearly a century, the St. Pierre Manufacturing Corp. has made steel products like horseshoes, tire chains and wire ropes in a facility in Worcester, Mass. Yet, despite the strong economy, St. Pierre, like many other American manufacturers, is struggling. Its problems stem from President Donald Trump’s tariffs on Chinese-made goods. The ongoing trade war “makes it a heck of a lot harder to compete,” says Peter St. Pierre, the company’s vice president of finance and operations and a grandson of founder Henry St. Pierre.

Trump imposed tariffs on imported steel and aluminum more than a year ago, later adding them on an additional $200 billion worth of Chinese goods. On May 10, as negotiations on a wider deal with China faltered, he said some tariffs would increase to 25% from 10%. His rationale is twofold: dissuading Americans from buying Chinese exports is meant to put some teeth behind trade-deal talks, with the added benefit of helping domestic companies by pushing consumers to buy American.

“The Tariffs can be completely avoided if you buy from a non-Tariffed Country, or you buy the product inside the USA (the best idea)” he wrote in a Twitter thread about China. “Make your product at home in the USA and there is no Tariff,” he continued in a separate thread on Tuesday.

Yet St. Pierre and its peers say that are hurt by the tariffs even though they do make their products in the United States, exposing one of the central challenges of the way the Trump Administration is waging its trade war. Though the debate over tariffs is practically an American institution, global trade today is a different beast than it was in the early 19th century, when tariffs on some imported materials helped jump-start the American textile industry. American manufacturers have been sourcing products and parts from around the world for decades, and today it is nearly impossible — not to mention extremely expensive — for companies to extract themselves from that global supply chain.

“In the last 20 years, businesses have become much more strategic,” says Kara Reynolds, an economics professor at American University. “More and more often, they are looking at where they can find the highest quality and lowest-cost parts so that they can be competitive.” As a result, an escalating trade war could isolate American manufacturers, quarantining companies and consumers from the increasing prosperity that’s come with a globalized economy. The rest of the world meanwhile continues to trade unencumbered.

The steel and aluminum tariffs have already hit American manufacturers across industries. Heavy-equipment makers like Caterpillar, beer sellers like Anheuser-Busch and automakers like General Motors all say costs have surged because of increased prices on those materials. (The Trump Administration lifted tariffs on steel and aluminum from Canada and Mexico on May 17, but the market is expected to remain tight.) Meanwhile, thousands of products, from seafood to electronics, are affected by the May 10 increase. “Almost no company isn’t going to import something from China,” said Michael J. Hicks, an economics professor at Indiana’s Ball State University.

The push to “Buy American” is as old as the nation itself. George Washington boasted of wearing “homespun” clothes to his Inauguration as a dig at the British, says Dana Frank, a professor emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and author of Buy American: The Untold Story of Economic Nationalism. (Washington’s clothes were made by his slaves.)

That rhetoric has resurfaced in moments of nativism — in the wake of rising anti-immigrant sentiment in the 1920s and 1930s, for example, Frank says. But in the aftermath of World War II, when the U.S. emerged as the strongest economy in the world, consumers and businesses alike concluded that protectionism might make it harder to sell overseas too. So they embraced free trade and the opportunity to send American products to countries whose own economies were in ruins. The world bought U.S.-made goods; manufacturers prospered; labor unions negotiated good deals for American workers. Global supply chains were established as early as the 1960s. By the time yet another “buy American” campaign peaked in the early 1990s, in part a response to Japanese-made cars having gained significant market share in the U.S., Frank says, “that train had already left the station.”

Now, even the most American-seeming products has parts from somewhere else. Not counting the engine and transmission, around 23% of a Corvette and 43% of a Ford Explorer comes from outside the U.S. and Canada, according to American University’s Made in America Auto Index. Budweiser — which literally branded its beer “America” in 2016 — makes some of its cans from imported aluminum, as does Coca-Cola. General Electric imports some parts from China for the high-tech medical equipment it makes in Wisconsin. And American retailers source many of their goods from overseas too; when Walmart pledged to buy more American-made goods in 2013, the $50 billion it committed made up just 1.5% of what it spent that year buying goods globally.

As for St. Pierre, the company made the decision to buy some parts overseas when it began to face growing competition in the 1970s from cheaper foreign products; prices had to come down if it was going to keep customers. Peter St. Pierre says his father used to get nervous to raise suggested retail prices by even a quarter. Now, with the tariffs, the younger St. Pierre is asking for $3 to $5 more. Further complicating matters: even the American-made steel the company already uses for its horseshoes is causing problems, its price having increased 40% over the past year as tariffs on Chinese steel intensified demand for the domestic product. “Everything we do here is steel-related,” says St. Pierre, “and over the last year or so, the price of steel has been going up and up.”

Today’s trade war comes at a particularly difficult time for U.S. manufacturers. E-commerce technology is making it possible for retailers to stock fewer items on shelves and to fill orders only when needed, resulting in better efficiency for stores but fewer orders for manufacturers. And rising minimum wages, while a boon to workers, are increasing labor costs. That means fewer units are being made, St. Pierre says, and each one costs more.

The problem is clear to business owners like Morris Kessler, who started an amplifier company in 1967. Today, that company, ATI, makes high-end amplifiers and audio equipment in Southern California. Kessler’s experience shows how tariffs put companies that source components globally but make products in the U.S. at a disadvantage: European competitors can undercut his prices because they can buy Chinese components without the added tariffs. Meanwhile, he suspects his Chinese suppliers are getting in on the trade war by raising prices as a form of retaliation, as parts he used to get for a penny now cost five cents. “This is hurting companies that never made anything in China,” he said.

Trying to source parts from the U.S. alone would be nearly impossible. As U.S. manufacturers stopped making products that were more available elsewhere — resistors and semiconductors for companies like Kessler’s, for example — Chinese suppliers filled the void. Establishing new supply chains would take years. “To replace a supplier is very difficult, and very expensive,” says says Charlie Chesbrough, a senior economist at Cox Automotive, which tracks auto industry trends. (The Center for Automotive Research estimates that about 12 percent of U.S. motor parts are imported from China.)

In fact, as the trade war continues, some American manufacturers may begin buying more parts from overseas, rather than fewer. Tube Forgings of America has made steel fittings for energy facilities in the U.S. since 1954; the fittings are made in Oregon, but the company has sourced carbon steel from overseas since the 1970s, which means it now pays the 25% tariff. Competitors that import finished products rather than raw materials into the U.S. aren’t paying one at all. So company president Jay Zidell says he’s exploring the idea of buying semiforged fittings overseas and importing them. That would mean closing down part of his plant and laying off workers. “What choice do we have?” he says.

Other companies have announced plant closings and layoffs since the tariffs were enacted last year. Arnold Kamler, the CEO of Kent International, wrote in a Washington Post op-ed published May 8 that the tariffs have stopped him from expanding his domestic bicycle manufacturing operations, because of rising duties on imported parts. A South Carolina plant that assembled televisions using Chinese parts said last year it was shutting down because of the tariffs. The Beer Institute, which represents 6,000 brewers and 2.2 million American jobs, said that about six percent of the cost of beer is the aluminum used in cans, and predicted that higher aluminum tariffs could cost 20,000 American jobs.

“It’s a hard situation for companies — even though they’ve invested in the U.S., President Trump and the tariffs are making it impossible to keep employment at current levels,” said Christina Fattore, a political science professor at West Virginia University. Manufacturing employment, which had been increasing steadily since the recession, has leveled off in recent months.

Some American manufacturers have adapted by charging more for high-quality products, but they worry that customers’ patience with higher prices is running out. In a 2017 Ipsos/Reuters poll, 69% of American consumers said price was very important to them and 77% said quality was, while only 32% said it was very important that a product was made in the USA. Many U.S. manufacturers are already selling products at a premium, because their workers have more labor protections and higher wages than those in China, and they fear the trade war may push prices past what consumers are willing to pay.

Which is why Peter St. Pierre is worried about tacking that extra couple of dollars onto price tags. Some retailers have already stopped stocking more expensive U.S.-made horseshoes in recent years, he says, and replaced them with lower-quality sets from China. “It may get to a point where not enough people are going to want to buy horseshoe sets made in the USA,” Peter St. Pierre says. “It really is getting more and more challenging.”‘

A version of this article appeared in the June 3-10, 2019, issue of TIME

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com