When Medicare was created in 1965, few Americans were talking about universal health care. Even fewer realized that the bureaucrats behind the program hoped that it would eventually become that.

With America at the height of Cold War anti-communist sentiment, the Social Security Administration staffers who set up Medicare did not articulate their goal, instead hoping that lawmakers would incrementally expand Medicare to include everyone — not just the elderly.

“The original idea behind Medicare was Medicare for all,” says Jonathan Oberlander, professor and chair of social medicine at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

Now, more than a half-century later, “Medicare for All” has become a slogan for a number of different proposals by Democratic presidential candidates, members of Congress and liberal think tanks to expand government-sponsored health insurance to more Americans.

In some ways, the phrase “Medicare for All” is better known among voters than more precise terms such as universal health care, single-payer health care, socialized medicine or government-run health care, but that same flexibility also means that it is not always clear what a candidate means when using it.

Here’s a closer look at how “Medicare for All” became a catchphrase in U.S. politics and what it means.

Advocating for universal health care

The idea of the government ensuring that people have access to health care began long before Medicare. While local governments experimented with health care for centuries, the first national health insurance program came from Germany’s Otto von Bismarck in the 1880s. Other European countries followed with their own versions of government health care for workers, and by the early 1900s, reformers in the U.S. were advocating for a similar system.

The push was closely tied to the labor movement, according to Northern Illinois University history professor Beatrix Hoffman, who studies the politics of health reform. But businesses and doctors attacked the idea of government health care, and it soon died. This opposition also killed President Franklin Roosevelt’s desire to add health coverage to the Social Security Act in 1935. And when President Harry Truman took up the cause after World War II, the American Medical Association and other opponents used Cold War scare tactics to paint “health security,” as it was known then, as socialized medicine and kill the plan again.

“The defeat of the Truman plan was so massive, it was such a big failure, that supporters decided they were going to stop trying for universal coverage,” Hoffman says. “That’s when they invented the idea of Medicare for the elderly only.”

From Medicare’s start, it was a popular program. But it also quickly became expensive, and the 1970s turned to discussions about how to control health care costs — not exactly a helpful political environment for those looking to expand coverage.

The first major change to Medicare came in 1972 when Richard Nixon added individuals with disabilities and those with end-stage renal disease. But this took the program in a fundamentally new direction: serving as a fallback for people who couldn’t get insurance through their employers, rather than building toward universal coverage as Medicare’s designers had hoped.

Amid these discussions about how to rein in health care costs, Sen. Ted Kennedy introduced his first national health insurance plan in 1971, proposing financing it through payroll taxes. But this failed, along with the rest of the plans discussed at this time.

Still, someone else did see hope in Medicare. One of these failed plans came from Republican Sen. Jacob Javits, who proposed expanding Medicare to cover the entire country’s population. Javits still used the language of “national health insurance,” but he became one of the first people publicly associated with the phrase “Medicare-for-all” when the New York Times used it to describe his plan, declaring on April 15, 1970: “Medicare For All Is Asked By Javits.”

Finding the right political message

This phrasing did not take off right away. The Vietnam War and Watergate pushed health care reform from most lawmakers’ minds, and then the 1980s ushered in the conservative Reagan era.

As Congress turned away from the issue, activists took up the charge. The 1980s saw the birth of groups such as Physicians for a National Health Program, which brought doctors together to advocate for universal health care, and the growth of the Gray Panthers, which had been founded to fight ageism and other social issues and made health care a major part of its agenda.

The advocacy groups of the ’80s started by using “national health insurance” to describe their goal, but soon moved toward the phrase “single-payer” health care. The latter meant that their ideal national health program would have just one payer — the government — as opposed to the many payers of the private insurance industry.

“As doctors we like to be very clear about what we’re advocating for. So ‘single payer’ was an accurate description,” Dr. David Himmelstein, co-founder of Physicians for a National Health Program, told TIME.

Though some doctors’ groups were part of the early opposition to single-payer health care, Himmelstein says he and his colleagues found that when they talked to individual physicians, many supported the idea of universal health care. In these years, other groups such as the American College of Surgeons also joined the fight.

As Himmelstein and his co-founder Dr. Steffie Woolhandler built their group, they were inspired by Canada’s national health program, also called Medicare. But in the 1980s, Physicians for a National Health Program did not initially use the Medicare framing because they still saw plenty of flaws in the American version of the system. While Medicare was helpful to many patients who used it, critics said that it didn’t cover all medical expenses, its payment policies were overly complex and it still relied too much on private industry.

In contrast, the language of “single-payer” health care symbolized a kind of political purity, according to Yale political scientist and health care policy expert Jacob Hacker. “There was some thought that the word ‘payer’ made clear that you were still purchasing the good kind of health care that people knew and loved,” Hacker says. “Before people saw Medicare as the platform, they wanted to say ‘payer’ because they didn’t want to say it’s about socialized medicine.”

However accurate single-payer might have been, it did not really catch on outside health policy and activist circles. “It’s like trying to sell a house by describing its plumbing,” Hacker says.

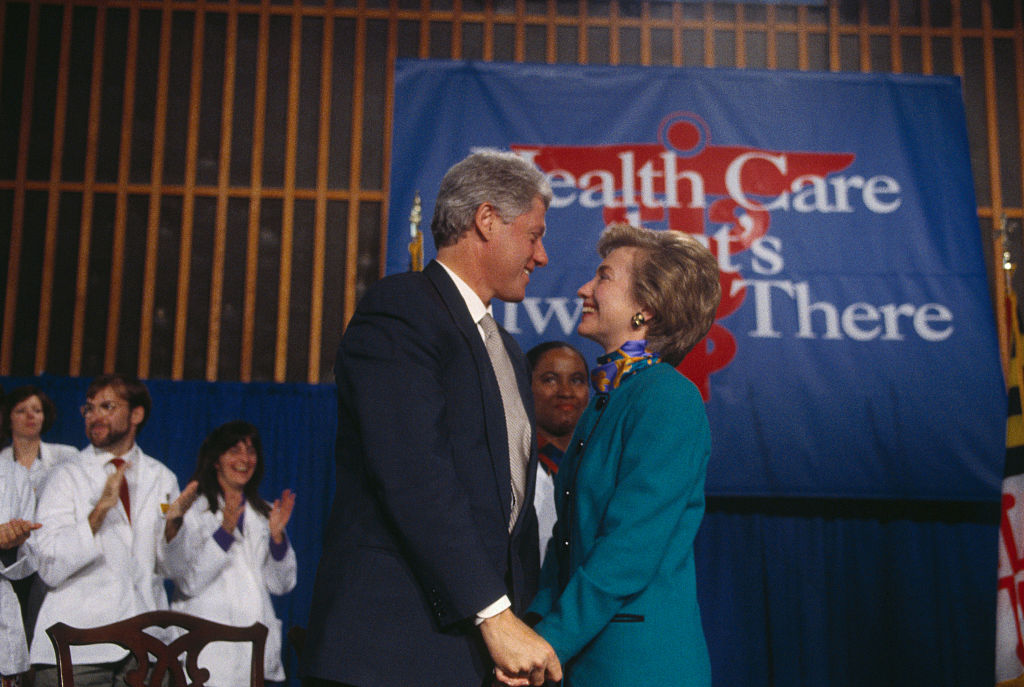

By the 1990s, Democrats geared up to tackle health reform again under President Bill Clinton. But the Clinton Administration intentionally distanced itself from the single-payer model, instead taking a more moderate approach and sought to expand coverage to everyone while preserving private and employer insurance.

“That represented a shift in Democratic thinking to the right, that the only feasible way to pass health care reform was one that built on the status quo and built on private insurance,” says UNC’s Oberlander.

Again, alternative plans popped up, and this time Rep. Pete Stark proposed enrolling uninsured people in what he called “Medicare Part C.” But like the Javits plan in the 1970s, this did not gain traction. Instead Democrats pushed the Clintons’ plan, which proved too complicated for voters and ultimately imploded, setting back the cause of major health care reform.

Returning to Medicare

The new millennium brought a Republican administration and a resistance to pursuing big health care changes. When President George W. Bush created Medicare Part D, the legislation did not allow the federal government to negotiate drug prices, leaving progressives feeling frustrated and powerless against the growing power of the pharmaceutical industry.

Despite this, the rest of Medicare had substantially improved since its early days. Reforms to the program had brought down spending, and it now had low administrative costs plus a demonstrated ability to control prices, often giving it an advantage over private coverage. That made it popular not only with recipients but also among lawmakers.

In this climate, “Medicare-for-all” finally arrived in Congress. In 2003, Rep. John Conyers introduced the Expanded and Improved Medicare For All Act, a bill that would create a universal single-payer health care system. His fellow lawmakers largely ignored it at the time, but Conyers introduced the bill in each session of Congress until he resigned in December 2017 in the wake of sexual harassment allegations. In 2006, Kennedy also tried again, introducing the Medicare for All Act, which proposed gradually expanding coverage to include all citizens and legal residents.

Though these bills were not successful, they signaled a coming change in strategy from the technical language of single-payer to the aspirational message of expanding on Medicare to create an even better system.

“There were concerns that it was hard to communicate what single-payer really means,” says Randy Block, chair of the National Council of Gray Panther Networks, who has been involved in health care advocacy since the 1970s. “A big portion of Americans do know about Medicare, and it’s a vehicle for building on existing systems and for helping the public understand that it’s possible to do a good job.”

If the first steps in moving toward the use of Medicare-for-all were about people recognizing the program’s efficiency and familiarity, the final one has come from a growing sense of frustration with the country’s current health care system. In the years leading up to the Affordable Care Act, the public ramped up its anger at the insurance industry. People were tired of high premiums, losing insurance over pre-existing conditions or going bankrupt to afford life-saving care.

Barack Obama entered the White House promising to do something about that. He initially supported the idea of a “public option,” which would let consumers who didn’t have coverage through work or other existing programs buy in to a Medicare-like government plan. But the public option idea died during the ACA debates, and the final law, while the largest health care reform since 1965, was criticized by those on the left for not going far enough and continuously attacked by those on the right.

“The lack of any bipartisan buy in for the ACA — which was designed in ways that the advocates hoped would encourage that kind of bipartisan buy-in — has meant that the advocates have said, if you can’t get significant Republican support or any Republican support, why don’t we do something we really want to, like expand Medicaid and Medicare?” explains Hacker, the health policy expert whose public option plan helped inspire the ACA.

Medicare-for-all advocates like Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders have certainly felt this way. The Senator has now put forth five versions of his Medicare for All Act, with the latest bill recently introduced in in April.

And his idea is increasingly popular. While his 2013 bill had zero co-sponsors, the current version has 14, including four of his fellow 2020 Democratic hopefuls. A recent poll from the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation found that support for a national single-payer health plan has increased 16% since 2000. And when it comes to the actual “Medicare-for-all” terminology, 63% of voters had a positive reaction to the phrase.

One thing experts note, however, is that voters are not always clear on what “Medicare-for-all” really means. The same Kaiser poll also found that when voters were told the details of health plans, 56% supported a true Medicare-for-all plan and 74% said they favored a proposal that would give them the option to buy a Medicare-like plan or keep their current coverage if they like it. This would actually be closer to Hacker’s new work, which led to the “Medicare for America” proposal that was introduced by Connecticut Rep. Rosa DeLauro and Illinois Rep. Jan Schakowsky in the House.

“I think the enthusiasm for Medicare-for-all has outpaced the changes in the political reality that would make Medicare-for-all possible. It’s still a really big lift,” Hacker says.

While several Democratic presidential candidates have supported Sanders’ plan, it seems that many are still navigating the nuances of what that means politically. New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker and California Sen. Kamala Harris, for example, have said they support “Medicare-for-all” but don’t want to get rid of private insurance, while Pete Buttigieg said he believes the best way is to provide “Medicare for all who want it” and Joe Biden similarly told voters they should have the option of a Medicare-like plan. Even Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren has said she is looking at “different pathways” to reach universal coverage.

“Because the enthusiasm of Medicare-for-all is growing among Democratic voters, other Democrats like many of those running for president are trying to tap into that enthusiasm,” says Oberlander. “They’re trying to use the rhetoric and rhetorical advantages of Medicare expansions while avoiding the political liabilities of Medicare-for-all.”

As politicians have seen over the past century, the political liabilities can be dangerous. But warnings of socialism are unlikely to have the same effect in the era of Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez that they did during the 1950s.

“Young people are not afraid of the word socialism,” Hoffman says. “I’ve noticed that is not the major line of attack anymore. The main thing that we hear now is how are you going to pay for it?”

These attacks may yet be successful. Just because a policy is popular among Democratic primary voters is no guarantee it can survive the general election, particularly against President Donald Trump. But even if no plan succeeds this cycle, experts and activists say the current wave of support for Medicare-for-all feels vastly different from previous reform efforts that died under Truman or Clinton.

“It’s not like people can come in and say let’s just do incremental reform. We did try that,” Hoffman says. “It’s not just that it didn’t completely work, but it was so vulnerable to attack. The only way to prevent that is to have full scale comprehensive reform.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com