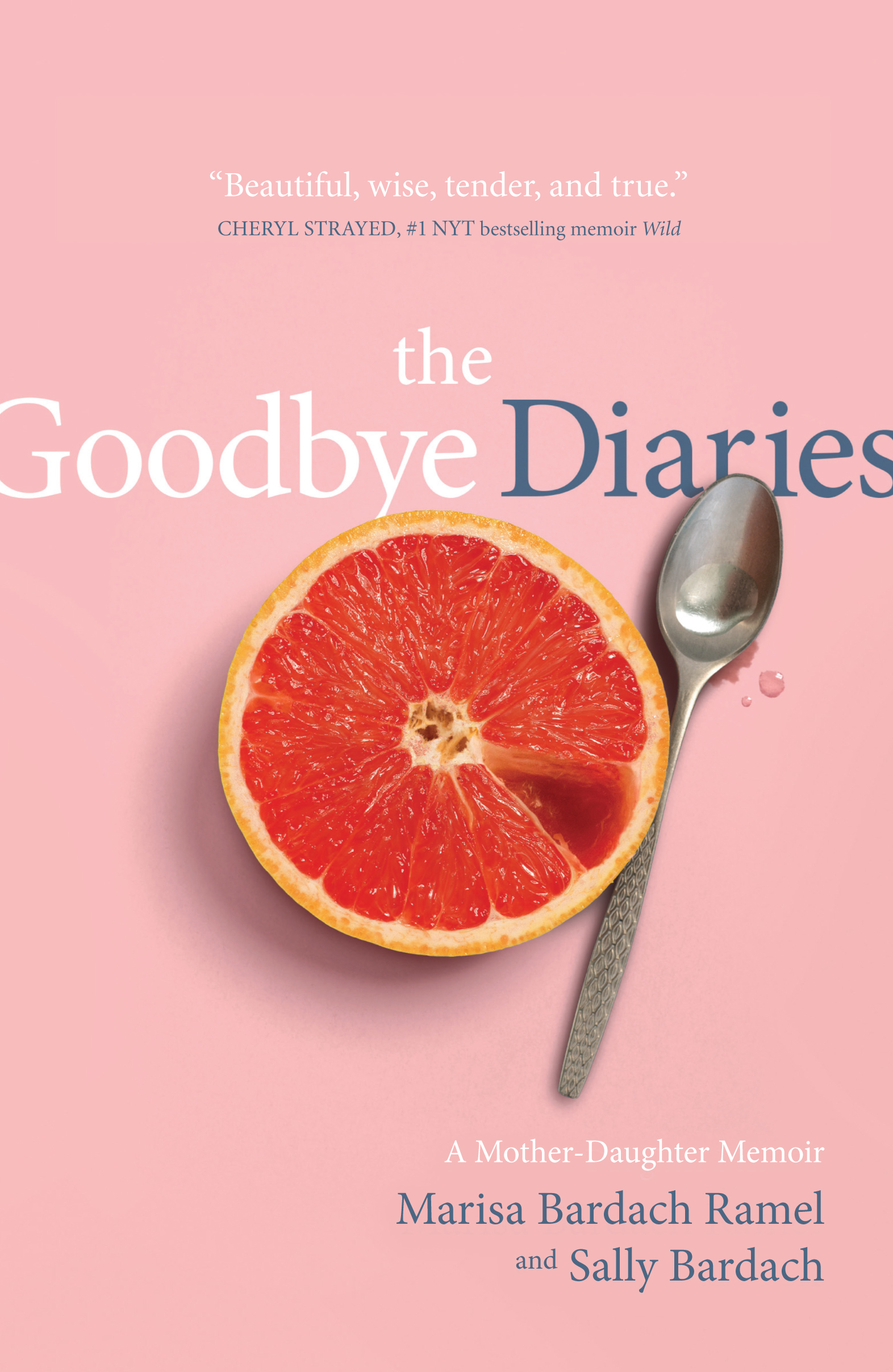

When Marisa Bardach Ramel was 17, her mother Sally Bardach was diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer. The pair decided to write a book together about their experiences as they faced down the encroaching reality of saying goodbye. Seventeen years following Sally’s death in 2002, the mother-daughter book, told in chapters that alternate between their perspectives, is being published as The Goodbye Diaries. The following excerpt was written while Marisa was pregnant with her daughter last year.

There’s something about newborns that seems infinitely wise and connected to all that came before. Perhaps it’s because babies, much like those who are leaving the world, travel through darkness and into the light. In the days before my daughter is due, I wonder if birth and death are inextricably linked, and if my children get special protection in those wondrous moments before and after birth. My mom, the true midwife into this world.

That’s why I sense that when my daughter is born, the heaviness inside me will crack open and flood out. I will tell her everything. About my mom, about my loss, about the grief I have carried around. And yet, once my daughter is born, I say nothing of my mother. I’m wordless when the doctor places her on my chest, silent when I nurse her while the rain drips down our hospital window. I should have known that, just as with my son, I can’t bear to burden her with my grief. Maybe she already knows everything. Maybe she truly knows nothing. I pet her puppy-soft dark hair and kiss her velvet cheeks and stroke the small of her back. And in the quiet with her, I feel understood.

I’m sent home from the hospital in time for Mother’s Day. After many spent in misery, this one is a miracle. In our sunny Brooklyn apartment, I lie on the couch and hold my newborn daughter close, her tiny ear pressed against my swelling heart. Instead of telling her about my mom, I tell her about the kind of mom I long to be. With my silence, I show her that I will always listen. I whisper that she can tell me anything—no judgment, no criticism, not a peep. I remember all the times I went upstairs to my mother’s room and lay quietly beside her until the words began to trickle out. I sense that, in the years to come, this is the only way my daughter, too, will reveal to me all the things deeply rooted in her heart.

The first time I cry while holding my daughter, she is three weeks old. I’ve just been told that my great aunt Ruthy—whose love and affection so closely mirror my mother’s, and who has become a second mother to me in her absence—is in the hospital. She is 98, yet I know it will always be too soon to lose her, that it will feel like losing my mother all over again. Tears drip onto my daughter’s dark hair, and I feel guilty for introducing her to my grief. But she doesn’t fuss or cry. Instead she fixes her piercing navy blue eyes on me and, for the first time, reaches out and grabs my hand. I hold her gaze, transfixed. Did my mother feel this way when I looked at her, when I held her hand? Even in my worst moments as a teenager, even in her worst moments of illness, did my mere existence ease her sorrow? I’ve always known that daughters seek the comfort of their mothers; it’s what I’ve been missing for years. But as my baby girl’s fingers clutch my hand, I realize that mothers draw strength from their daughters, too.

My daughter won’t know her Grandma Sally, not in the way she knows her other grandparents—her Nana and Grammy and my stepmother Tippy. But my mom will not be absent from her life, either.

My son, at three years old, already knows about Grandma Sally. He has curled up in my lap to look at countless photos and watch old home videos. He’s even placed stones on her grave, a Jewish tradition. But, for a toddler, it’s just rocks to collect and a grassy field to run around. He still seems too young to know what happened, or maybe I’m just not ready to hear her death come out of his mouth. I don’t want him to know that mommies die.

With my daughter, it’s simpler. Telling her about my mother requires no words; her presence is that near. She is my hands whenI pet my daughter’s hair. She is my heart beating into my daughter’s ear. She is the very essence of who I long to be as a mother, and who I inevitably am. Most daughters cringe at the idea of becoming their mothers; I welcome the transformation. I only hope I’ll be able to create the same indelible bond between mother and daughter. In sickness and in health. ’Til death do us part. The unspoken vows we solemnly swear to our children.

One day I’ll tell my son and daughter the truth about my mother dying. I’ll read some books and try to find the right words. I’ll say it in a way that’s gentle and loving and thoughtful, just as my mother would have done with me. I just need the courage to do it. Until then, I’ll feed them her favorite fruits and recipes. I’ll explain the world around them with her teacher’s patience. I’ll share her funny stories and hear her loud laugh in my own. I’ll smother them with the endless love and affection she poured into me. For so long, my mother’s death overshadowed all the memories that came before. Now, with my children, I get to share the best parts of my mother: the parts where she was alive.

Excerpted from The Goodbye Diaries: A Mother-Daughter Memoir by Marisa Bardach Ramel and Sally Ramel, published by Wyatt-MacKenzie on May 7, 2019. Copyright ©Marisa Bardach Ramel. Used by permission.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com