There have always been touchy-feely guys, and it’s not always easy for a woman, especially in the moment, to know how she should feel about it. There’s the colleague you don’t see very often, who kisses you affectionately on the cheek when he sees you. If you’ve read each other’s cues and you both know it’s OK, there’s no problem. But what if you don’t like it? Might objecting somehow undermine you in a world where men and women have to work together? There’s the uncle-in-law who, during a friendly embrace, puts his hand in a spot that’s either too high or too low, you’re not quite sure—but it’s not a capital offense, so you laugh it off. Does that make you a tool of the patriarchy, an enabler of old-school “boys will be boys” behavior? How much do we put up with? And why do we feel we need to put up with anything at all?

In its short life so far, the Me Too era has been a period of justified anger and understandable relief, as women have realized that when they speak up about abuse, assault and harassment, others are, at last, poised to listen. But in any exchange between men and women—or between people who, whatever their gender or orientation, possess human sexual impulses—there are gray zones, and even in the context of women’s newfound space to speak up, we don’t always have the mechanisms to deal with them. Most sane, sensible people, once they’d heard women’s testimonies, wouldn’t hesitate to stand behind Harvey Weinstein’s accusers. But on social media or in casual conversation, anyone expressing doubts about less clear cut accounts—as in, “Maybe that Aziz Ansari thing was just a bad date between two people with differing expectations and not cause for public outrage”—had to tread carefully. The prevailing mentality has been: “You’re either with us or against us.”

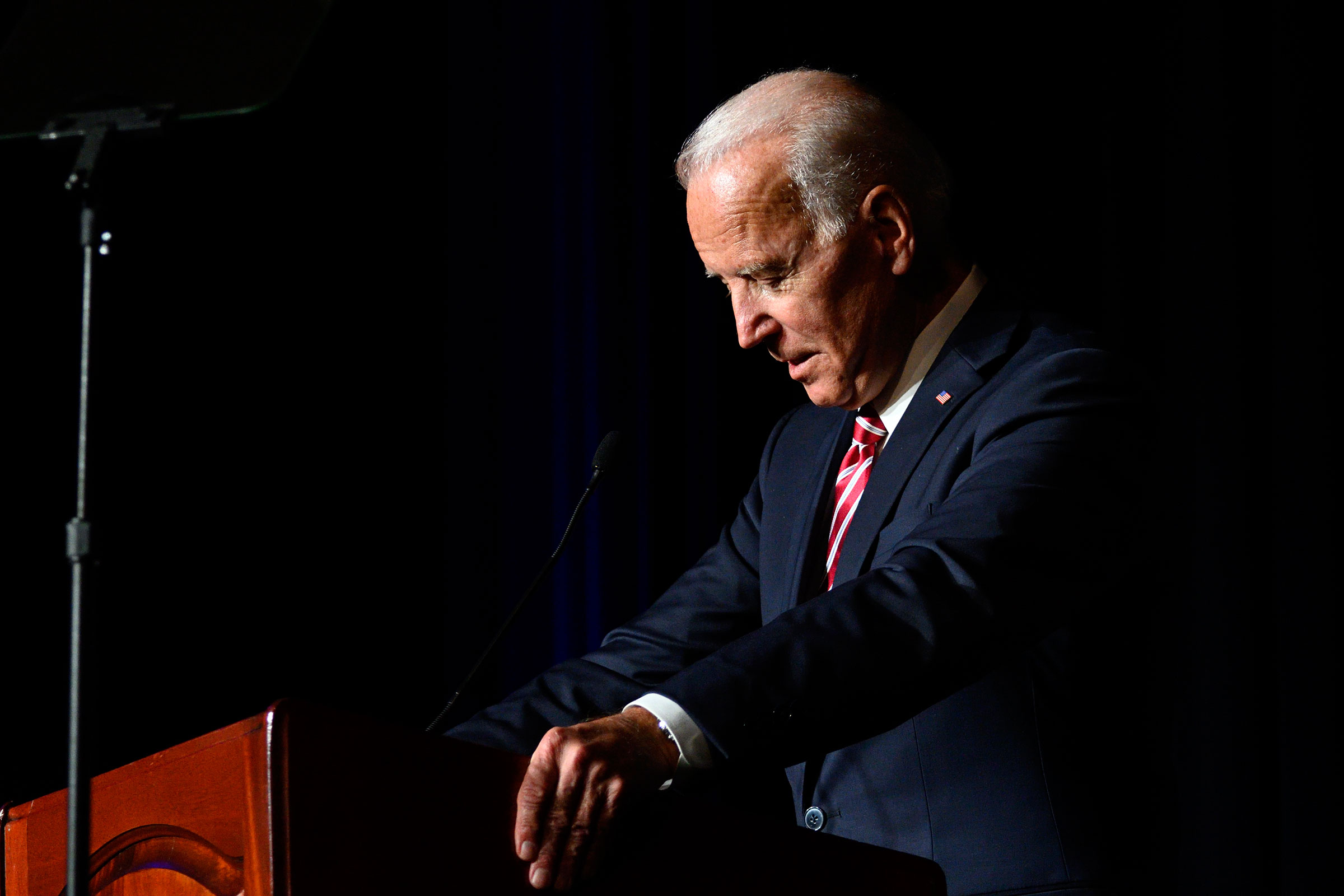

But now, one clumsy, seemingly benevolent guy has shifted the conversation. No one knows quite what to do with Joe Biden and the inappropriate-touching flap stirred up in the weeks before he announced his presidential candidacy on April 25. Internet outrage fizzled, and in its place is a kind of whispered questioning. Men are asking themselves, What kind of touching is OK in a public or professional setting? And women are asking, Do we really have to be radically aggrieved by every instance of sexism or disrespect, without weighing the intentions of the accused? And what is the proper punishment—if there ought to be a punishment at all—for a guy who has not assaulted or abused us but has made us uncomfortable?

In a March 29 essay on New York Magazine’s The Cut, Former Nevada assemblymember Lucy Flores opened the conversation around Biden’s handsy behavior—and thus his unsuitability for the job of President—by writing about a 2014 incident in which Biden, during a political event, put his hands on Flores’ shoulders, smelled her hair and slowly kissed the back of her head. In the essay, Flores said the incident made her feel embarrassed, shocked and confused. She found Biden’s behavior “demeaning and disrespectful,” and spoke of the “power imbalance” between Biden and the women he feels so comfortable touching.

In the days that followed, several other women came forward to say that they, too, had been on the receiving end of Biden’s inappropriate touching. But while no one is claiming these women aren’t telling the truth—who doesn’t know about Biden’s space-invader impulses?—their accusations didn’t unleash torrents of anger over Biden’s behavior. In fact, according to polling data from Morning Consult for the week of April 1 to 7—the week after the allegations against Biden became public—34 percent of Democratic women cited Biden as their first choice for the party’s nomination; polling results from the previous week had been roughly the same. With exceptions, of course, few women in the press or on social media condemned Biden; eventually, the conversation settled into confused silence.

Many women on the left, it seems, aren’t so much angry with Joe Biden as they are frustrated with Uncle Joe, a seemingly well-meaning bumbler who’s constantly sabotaging himself with his own exuberant impulses. Biden’s touchy-feeliness has been the stuff of memes for years, and it’s usually been easy enough to brush it off with a “There he goes again” eyeroll. But the stakes are higher now that he has entered the race, especially at a time when there’s so much focus, finally, on female leaders. The party and the women voters within it have to reckon with what Biden’s behavior toward women means—if it has any significant meaning at all.

In political terms, there’s plenty to be said about Biden and his suitability, or lack thereof, for the presidency. But our discussion of this thing we can refer to only by the nebulous label “inappropriate touching” is far more complex. By talking about it, we may be able to get men and women closer to understanding what is and isn’t OK—and also to acknowledge that women have different benchmarks for what they consider harassment, or what makes them uncomfortable. The onus may be—as always—on women to speak clearly about what they want from men, but also to listen to other women, without judgment, who may have different benchmarks.

Our personal comfort zones are personal for a reason: they’re specific to each of us. How are we, as women, supposed to respond when a man violates another woman’s personal space—a violation that’s personal for her but not for us? Are we supposed to respond with a unibrain rallying cry of support? And if we’re uncomfortable with that kind of blanket defense, are we traitors to the idea of believing women? The Me Too movement has provided a vital gateway for women to stand up to abusive men. But it has divided women too, in ways that aren’t always easy to talk about. We might believe a woman’s account, yet also feel some sympathy for the object of her complaint. In these gray areas, who decides which degree of gray is acceptable? Maybe women, as well as men, have something to learn from the Joe Biden fracas—not about men, but about each other.

If we give Biden the benefit of the doubt and assume his touching is just inappropriately expressed exuberance, then he’s the perfect example of the Clueless Older Guy who just doesn’t know any better. We talked about this guy a lot in the early days of Me Too: What were we supposed to do with men who’d been in the workplace (or the world) for a long time and who grew up with different rules for what kind of behavior is acceptable? How quickly were they supposed to change? Was it our job to help change them? And if so, ugh! Didn’t we already have enough work to do?

These are things many of us have been thinking about for years, even before the hashtag went viral. And our uncertainty about what, exactly, to do with the Clueless Older Guy may explain why relatively few women are ready to damn Biden outright—though for many on the left, the inappropriate-touching controversy has opened a channel to express frustrations with him as a potential candidate. “Just so pissed at Joe Biden,” political writer Ana Marie Cox tweeted on April 3, five days after the appearance of Flores’ essay, a blurt of exasperation that felt reflective of the free-floating irritation many women were feeling at the time.

Many seem to be angry with Biden less for his transgression of personal boundaries specifically and more for what they see as a larger pattern of disrespectful behavior, stemming, at least in part, from his poor handling of Anita Hill’s testimony in 1991. We’ve also gotten mixed signals from Biden: The same guy who sponsored, and continues to support, the 1994 Violence Against Women Act, and who was one of the architects of It’s On Us, an initiative to educate the public about sexual assault, doesn’t automatically understand how wrong—or even just how weird—it is to kiss the back of a woman politician’s head during an event? (And that happened in 2014, the same year Biden helped launch It’s On Us.) After Flores’ essay ran, Biden issued a video statement in which he vowed to be more mindful of others’ personal boundaries going forward; some see this “apology” as inadequate. In The Atlantic, in early April, Megan Garber likened Biden’s statement to what she sees as the non-apology Biden has offered Hill; the day Biden announced his candidacy, Amber Phillips expressed similar reservations in the Washington Post. (Addressing the audience at the Biden Courage Awards on March 26, Biden praised Hill for speaking out about the harassment she suffered at the hands of Clarence Thomas, and also said, “To this day, I regret I couldn’t come up with a way to get her the kind of hearing she deserved, given the courage she showed by reaching out to us.”) And Flores continues to stress the importance of talking about Biden-style invasions of personal space in the context of Me Too. “It should include the entire spectrum of when our spaces, our bodies, are violated without our consent,” she said in an April 6 interview with Teen Vogue.

Even so, Biden isn’t a clear-cut villain here. Many women seem to accept where, as an older guy, he’s coming from, even if they can’t condone his behavior, or can’t fully square that behavior with, say, his involvement in establishing VAWA. In an early-April article on Elle.com, human-resources expert Lucy Adams noted that, based on her experience, she’d guess that Biden was feeling “a little bit bruised and embarrassed” after being called out on his behavior—and said that when you talk to a man about something he’s gotten wrong, “what you usually see is a period of reflection, if he’s a decent human being.” She also set out a three-step approach to dealing with the clueless older guy in the workplace, the first of which is to address the behavior outright, using humor if possible, followed by speaking out more directly and firmly. The third step, going to HR, is applicable only in the workplace, but the overall tone of Adams’ approach seems healthy: If crossed signals are the problem, the first thing is to try to uncross them.

Adams’ sympathy for Biden reflects what many felt when the whole controversy began. As dumb as it may sound, some men just don’t know any better, and if nothing else, the allegations against Biden have at least set some guidelines for them. Attention, dudes, especially older ones with a tendency to be physically demonstrative! Take better care not to invade a woman’s space. Don’t treat her like she’s adorable. Don’t put your hand on her knee. Don’t move in close, as if to rub noses. You may not need to be told to do any of these things—but if you’re ever moved to do them, think twice.

If nothing else, the Biden mess at least gives us a reference point for our own personal threshold of what’s acceptable. Younger women, especially, seem to be exasperated that we have to educate men at all, but the reality is that men learn a lot from women. There are just some things we notice about the way men behave—things they have done for years without thinking, simply because no one has called them out. There’s no magic formula that will make all men behave properly, but talking to them directly about what bugs us is a start.

It’s just as well we’ve already started having this discussion as it pertains to Biden: We’re going to be seeing a lot more of him in the months ahead. How does his behavior measure up to his promises, and against his stated policies? And in the context of larger political upheaval and division, is Biden’s touchy-feeliness such a big deal? We have the right to ask those questions. But the worst thing we can do is to let our resentment harden into a culture of punishment, where accusations fly but nobody strives to understand anyone else. We live in a complicated, sometimes dangerous world, where men and women have to get along whether they like it or not. The gray zones hold all the stuff we don’t really want to talk about. But it’s the gray zones that may be our salvation.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com