When she saw an official-looking blue car pull up in her driveway on April 24, 1967, Helene Knapp knew the news could not be good. Her doorbell rang and an Air Force Colonel and an enlisted woman entered her home. Helene listened with her stomach in knots. Her husband, Air Force pilot Major Herman “Herm” Knapp, had been shot down over Vietnam where he was fighting in the American air war against the North Vietnamese Communists.

Helene was told her husband might still be alive and that he was classified for the time being as an “MIA” or a “missing in action” serviceman. She was cautioned that she must say nothing at all about his situation to anyone but her closest family members. Her immediate thought was of how ludicrous that request was. How does one live a daily life keeping such a life-changing situation a secret?

This was Helene’s initiation into a “reluctant sorority” of MIA and POW wives — a club no one wanted to belong to.

One of the universal experiences shared by all the women in this group was the American government’s admonition to keep quiet about their husbands’ perilous scenarios. If the women dared to discuss it, their government warned them, the men might be badly treated or even executed. With this heavy burden to bear, the women were supposed to go about their daily existence, telling no one what they were up against. Supposedly this would help bring the men home safely. This policy had been applied to prisoners and missing troops in previous wars and was one President Lyndon B. Johnson would also adhere to during the Vietnam War. The U.S. government tried to use its well-worn template of “quiet diplomacy” to reason with the North Vietnamese.

But this approach didn’t work. In fact, it turned out that silence on the part of the American government allowed the North Vietnamese to avoid an accurate accounting of missing American servicemen indefinitely.

The POW and MIA wives ultimately realized that they knew more than anyone else about the situation. Many of the women were coding secret letters to their husbands right under the noses of the U.S. military and receiving replies detailing the prisoners’ desperate plight. They could not stand by anymore and listen to the inept dictates of their government. Even worse, LBJ and his ambassador in charge of POW matters, Averell Harriman, both knew of widespread torture among the POWs but chose to cover it up, not wanting to draw more attention to an already unpopular war or embarrass the North Vietnamese during negotiations. So the wives turned against all their training as conservative 1960s military wives, rejected the “keep quiet” protocol and followed their own rulebooks.

What the women suspected might work instead of the traditional diplomatic tactics was to use the world media to help shame the North Vietnamese into compliance. Sybil Stockdale, the wife of the highest-ranking naval POW, Jim Stockdale, was the first to go public with her husband’s plight, in October of 1968.

With Sybil as its first National Coordinator, the National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia was incorporated in D.C. on May 28, 1970.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The group used letter-writing campaigns, bumper stickers, brochures, public speeches and, most of all, television to get their message across. They had done what so-called “Wise Men” like Harriman and “Whiz Kids” like Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara couldn’t seem to do: put the North Vietnamese on the defensive by raising international awareness of the torture of American POWs and the extensive violations of the Geneva Conventions of War regularly occurring in Vietnamese prison camps.

Soon after Richard Nixon was elected President in 1968, the American government’s attitude changed dramatically. New Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird urged the administration to officially drop the “keep quiet” order and to allow the POW-MIA families to speak out with the American government’s support. After some initial resistance to this idea, the new Nixon administration agreed to support the policy change. Nixon soon came to understand the public relations value the POW-MIA women could provide. Helping American POWs and MIAs was a unifying cause for the entire country — something citizens from across the political spectrum could agree upon. This alignment of goals and values between Nixon and the POW-MIA wives spotlighted the cause even more, further empowering the National League.

In 2016, Senator John McCain told me in an interview that the POW-MIA wives’ “go public” approach had made a notable and immediate difference in the treatment of the POWs in the prison camps starting in 1969. “Our treatment changed dramatically. It went from bad — in my case, solitary confinement–to being with 25 others…it was a decision made by the Politburo. It was not gradual.” McCain went on to say of his fellow prisoners, “some of us may not have been alive had it not been for that change in treatment.” When I asked if “Keep Quiet” had been the wrong call, he nodded his head emphatically.

It took courageous women like Sybil Stockdale and her League of Wives to speak to truth to power — and to rescue the men that the Johnson administration had all but abandoned.

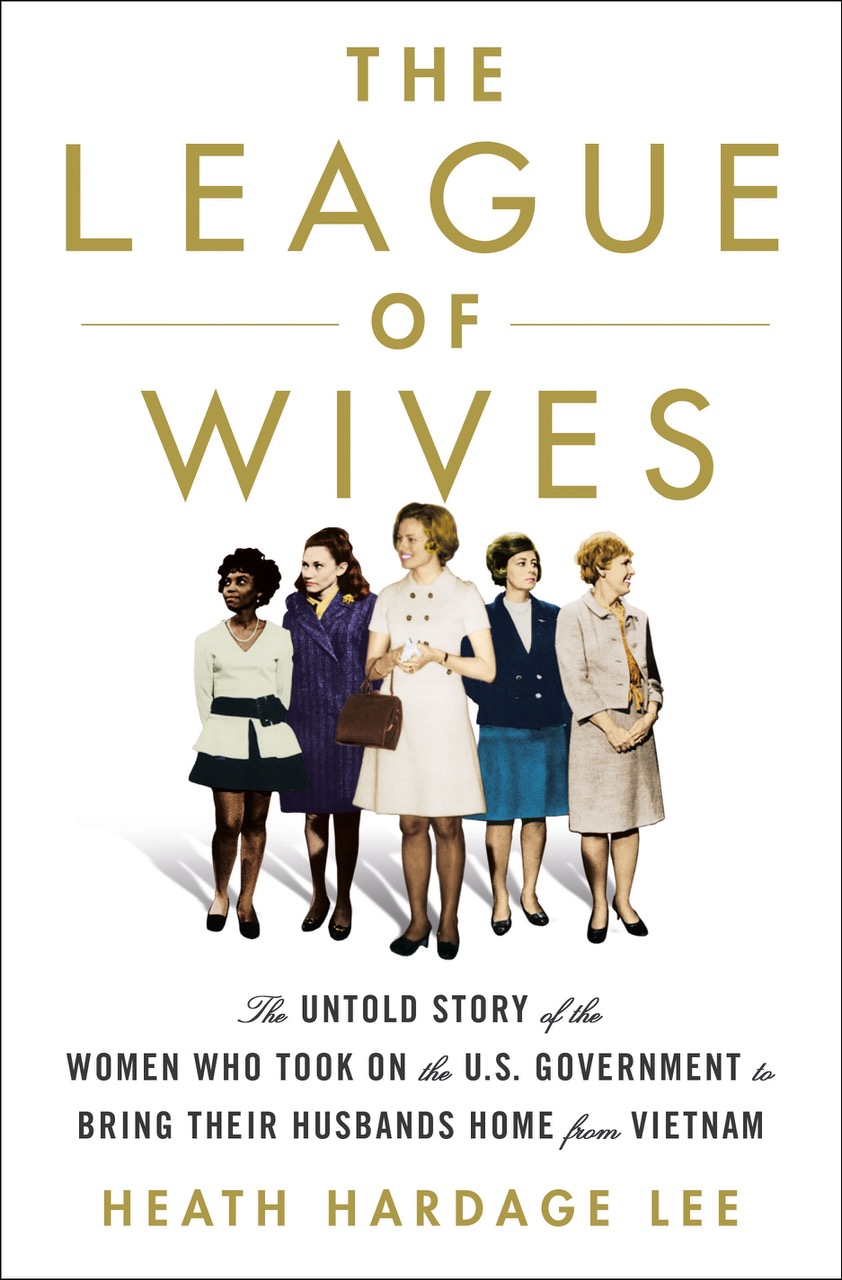

Heath Hardage Lee is the author of The League of Wives: The Untold Story of the Women Who Took on the U.S. Government to Bring Their Husbands Home, available from St. Martin’s Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com