It’s the voice you notice first. In person, David Attenborough speaks in the same awestruck hush he has used in dozens of nature documentaries, a crisp half whisper that is often mimicked but seldom matched. Ninety-two years of use may have softened its edges, but still it carries the command of authority. Sitting in his home in the Richmond neighborhood of west London for one in a series of conversations, I feel compelled to drink a second cup of tea when he offers. It somehow seems wrong to say no.

In his native U.K., Attenborough is held in the kind of esteem usually reserved for royalty. Over decades–first as a television executive, then as a wildlife filmmaker and recently as a kind of elder statesman for the planet–he has achieved near beatific status. He was knighted by the Queen in 1985 and is usually referred to as Sir David. As he walked into the Royal Botanic Gardens for TIME’s portrait shoot on the day of our interview, the mere sight of him caused members of the public and staff alike to break into goofy smiles.

Attenborough pioneered a style of wildlife filmmaking that brought viewers to remote landscapes and gave them an intimate perspective on the wonders of nature. Frans de Waal, the renowned Dutch primatologist, says he regularly uses clips from Attenborough’s shows in lectures. “He has shaped the views of millions of people about nature,” he says. “Always respectful, always knowledgeable, he takes us by the hand to show us what is left of the nature around us.”

In the autumn of his life, Attenborough has largely retreated from filmmaking on location but lends his storytelling abilities to wildlife documentaries in collaboration with filmmakers he has mentored. His most famous work, the 2006 BBC series Planet Earth, set a benchmark in the use of high-definition cameras and had a budget equal to that of a Hollywood movie. Among its highlights was the first footage of a snow leopard, the impossibly rare Asian wildcat that hunts high in the Himalayas. More than a decade after its initial release, Planet Earth remains among the all-time best-selling nonfiction DVDs.

Now Attenborough is putting his voice and the weight of authority he has accumulated to greater moral purpose. In recent months he has stood in front of powerful audiences at the 2018 U.N. climate talks in Katowice, Poland, and the 2019 World Economic Forum at Davos, in Switzerland, to urge them into action on climate change. These kinds of events are not his chosen habitat, Attenborough tells TIME. “I would much prefer not to be a placard-carrying conservationist. My life is the natural world. But I can’t not carry a placard if I see what’s happening.”

Attenborough and his frequent collaborators, filmmakers Alastair Fothergill and Keith Scholey, will attempt to show the world exactly what is happening on April 5, when Netflix launches Our Planet–a new, blockbuster eight-part documentary series that aims not just to present the majesty of the world around us but also raise awareness of what the changing climate is doing to it.

Filmed across every continent over four years, the show takes viewers from remote steppes to lush rain forest to the ocean floor. It has vertiginous ambitions in both its scope and intent. “The idea was not just to make another landmark show, but also to move the dial,” says Scholey, who served as an executive producer. “Not only do we engage a large audience but also actually get to the point of changing policy that would lead to global change.”

It’s a show perfectly timed for a global moment in which politicians are prioritizing climate change as never before, students are skipping school to attend climate marches, and governments are attempting to rein in carbon emissions to meet Paris Agreement targets. Although he has been criticized for not speaking up earlier, Attenborough now says that if he has the opportunity to speak truth to power, he has to take it. “It is important, and it is true, and it is happening, and it is an impending disaster,” he says.

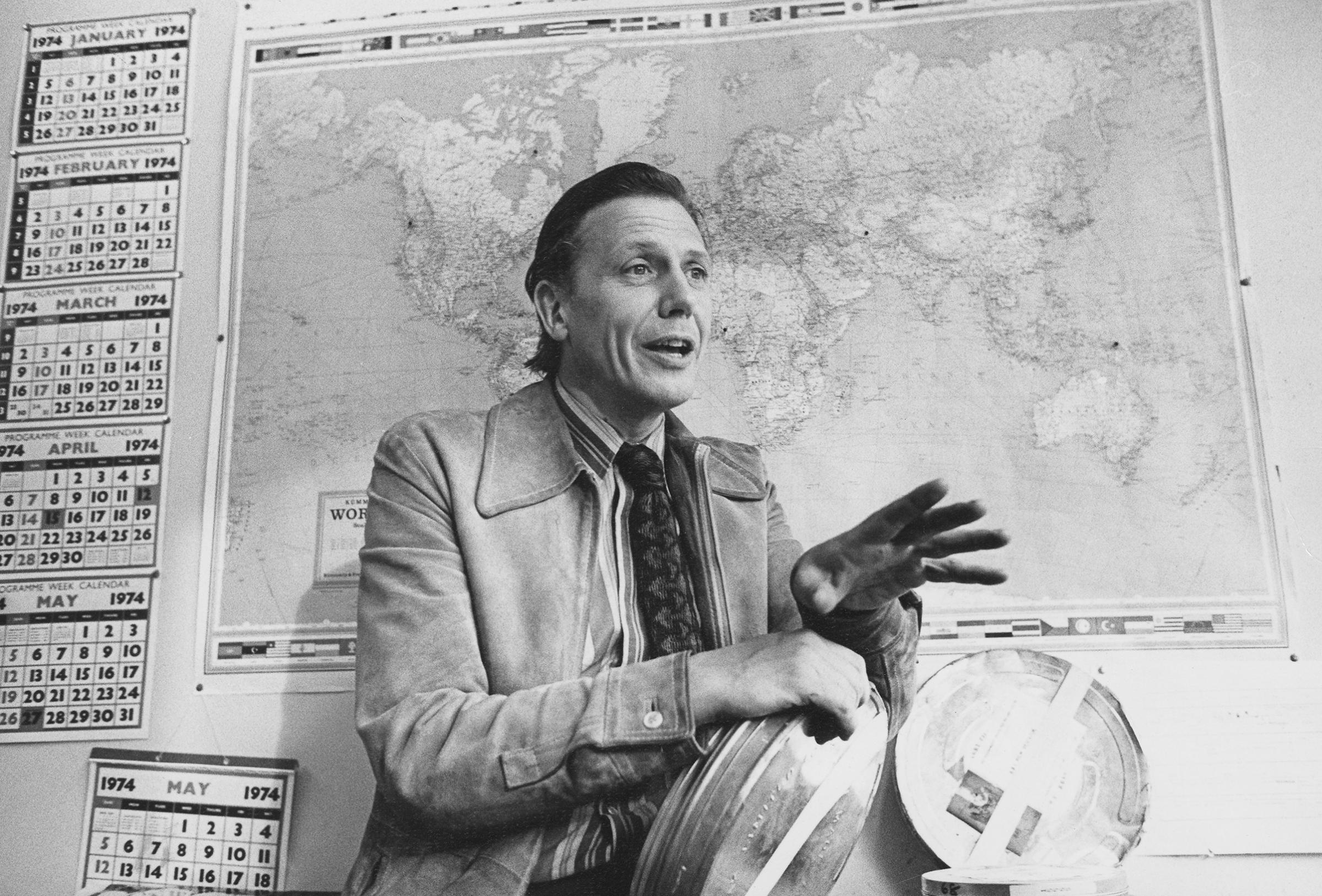

Long before he was a world-famous documentarian, Attenborough was a trailblazer in the medium of television. He went from being a junior producer at the BBC in the 1950s, making programs about “gardening and cooking and knitting,” he says, to becoming one of the first controllers of BBC Two, the corporation’s eclectic second flagship channel. Among his commissions was a quirky comedy-sketch show called Monty Python’s Flying Circus. He was prouder, he recalls, of commissioning an opera by the composer Benjamin Britten.

Having studied natural sciences at the University of Cambridge, Attenborough juggled his TV duties with making wildlife films every few months; his series Zoo Quest, which ran from 1954 to 1963, followed the London Zoo’s attempts to gather rare animals for its menagerie from West Africa, South America and Southeast Asia. “I’d go away for three months and make some programs, which was lovely,” he says. “But in between, I had to do all these other things … politics and finance and engineering, which was never my bag.”

In the early 1970s, he resigned from the BBC to dedicate himself full time to wildlife filmmaking. He soon began work on Life on Earth, the seminal 1979 series that traced the arc of evolution from primordial ooze to Homo sapiens. The 13-part broadcast took viewers around the world, bringing them into close contact with a range of animals and using then cutting-edge filming techniques like the slow-motion capture of animal movements. Its most famous sequence shows Attenborough cavorting with a family of mountain gorillas in Rwanda.

But while Attenborough’s filmography made him a household name in the U.K., his fame didn’t immediately transfer stateside. He remembers being in a pitch session with a major U.S. network trying to describe Life on Earth to an executive. “I remember saying, ‘We’re going to start from the very beginning of the primordial oceans and see when life begins to appear.’ And he said, ‘You mean the first program’s all about green slime?’ I said, ‘Well, yes.’ ‘No, thank you,’ he said.”

This skepticism about his appeal would last for decades. When the Discovery Channel decided to broadcast Planet Earth in 2007, his voice-over was replaced with one by the actor Sigourney Weaver. Yet the incredible popularity of the DVD collection–carrying Attenborough’s narration, it sold 2.6 million copies in its first year of release–won him a narrow yet fervent U.S. fan base. Among his admirers was President Barack Obama, who invited him to the White House in 2015 to discuss the threat of climate change in a televised interview.

Attenborough initially assumed he would be the one interviewing Obama. But he was astonished to discover the President wanted it the other way round. “I thought, I mean apart from my work, what’s he doing talking to me?” he says. He desperately boned up on figures on climate change, even calling the U.K. environment ministry to check statistics.

His profile is evidently now high enough for Netflix to tout him as the narrator of Our Planet for English-speaking viewers (Penélope Cruz and Salma Hayek narrate for Spanish-language audiences), although he admits his creative role was mostly limited to the voice-over. He didn’t travel to remote locations for the new series, focusing his efforts instead on helping producers craft a script that would suit his signature narrative style while also fulfilling the show’s brief to sound the alarm about a changing planet. “In the old days I wrote every shot,” he says. “These days it’s a lot more … professional.”

Although Planet Earth, as well as his other acclaimed BBC series Blue Planet and Frozen Planet, did raise concerns among some viewers about the state of the environment, Our Planet is more explicit in its messaging. This is in part because the filmmakers, freed from the rigorous impartiality of the state-funded BBC, teamed up with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), a conservation NGO. In one jaw-dropping sequence, after thousands of Pacific walruses are forced by vanishing ice sheets to crowd on a rocky strip of land, hundreds leap off a cliff to their doom, a scene Attenborough says is “almost heartbreaking” to watch.

Yet there are also scenes of hope that remind viewers that at least some environmental damage can be reversed. We see that Chernobyl–the Ukrainian region depopulated after a nuclear disaster in the 1980s–now has seven times more wolves than the surrounding countryside. Drone-mounted cameras show us one of the largest gatherings of humpback whales ever filmed, illustrating how marine preservation has permitted the species to bounce back from near extinction. To accompany the series, the WWF has created an online information hub so viewers can learn more about how to get involved in such efforts.

And yet even as he tries to spur action, Attenborough confesses that he has trouble staying optimistic. “The question is, Are we going to be in time, and are we going to do enough? And the answer to both of those is no,” he says. “We won’t be able to do enough to mend everything. But we can make it a darn sight better than it would be if we didn’t do anything at all.”

The reality of our changing planet is something Attenborough, who has seen more of it than most people alive, has long been aware of. For decades, he has decried the tendency of human development to crowd out natural habitats. He was present at the founding of the WWF in 1961, he says, even though he was just a “junior pipsqueak” at the time.

But it wasn’t until relatively recently that Attenborough became certain of mankind’s role in climate change. It sounds surprising given his body of work, but as he tells it, he didn’t want to base his judgment on observation alone. “It’s very dangerous to take a worldwide phenomenon and think you’re going to find just one scene in one locality that will prove it’s actually happening,” he says.

It was a 2004 presentation by the late U.S. environmental scientist Ralph Cicerone that convinced him of what was happening. “He showed a series of graphs that showed, with no doubt whatsoever, how population growth and industrial affluence had sent the content of noxious gases in the upper atmosphere,” he says. “And I had no hesitation after that.”

Still, some critics have argued that Attenborough and his colleagues have not done enough in their films to show the devastating effect of climate change. In a column for the Guardian in November, for instance, the environmental writer George Monbiot attacked the veteran broadcaster for “his consistent failure to mount a coherent, truthful and effective defense of the living world he loves,” and said wildlife television “cultivates complacency, not action,” by focusing on beauty rather than destruction.

“What George does is preach to the converted,” Attenborough says in response. By contrast, he explains, television makers have to speak to a wider audience. “You cannot do every program saying the world is in danger. Because they’ll say, ‘O.K., O.K., we get the message’ and go back to listening to something else. But we can say that the natural world is a wonder and a thrill and an excitement. And that’s what we do.”

There’s evidence this approach is as capable of sparking change as outright activism. Blue Planet II, the 2017 BBC series that explored life deep below the ocean’s surface, inspired a groundswell of activity after its final episode showed in detail how plastics are getting into the marine food chain. At the show’s conclusion, Attenborough told the audience “the future of all life now depends on us.” The resulting public outcry helped pressure the British government to enact restrictions on single-use plastics.

“Blue Planet II moved the dial in this country more than anything I’ve ever seen,” says Fothergill, an executive producer on Our Planet. “For a long time, conservation and wildlife filmmaking was about pretty animals. Now it’s about saying that without this biodiversity there won’t be air to breathe or water to drink. It is about empowering people.”

At the age of 92, Attenborough remains committed to that mission. The BBC has announced new sequels to Planet Earth and Frozen Planet, and he says he was recently contacted about a show due to air in 2026, when he will turn 100. After seven decades in the business, Attenborough marvels at the life he’s still able to lead. “I’m very surprised I’m still employed,” he says. “But I’m just very grateful I am.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com