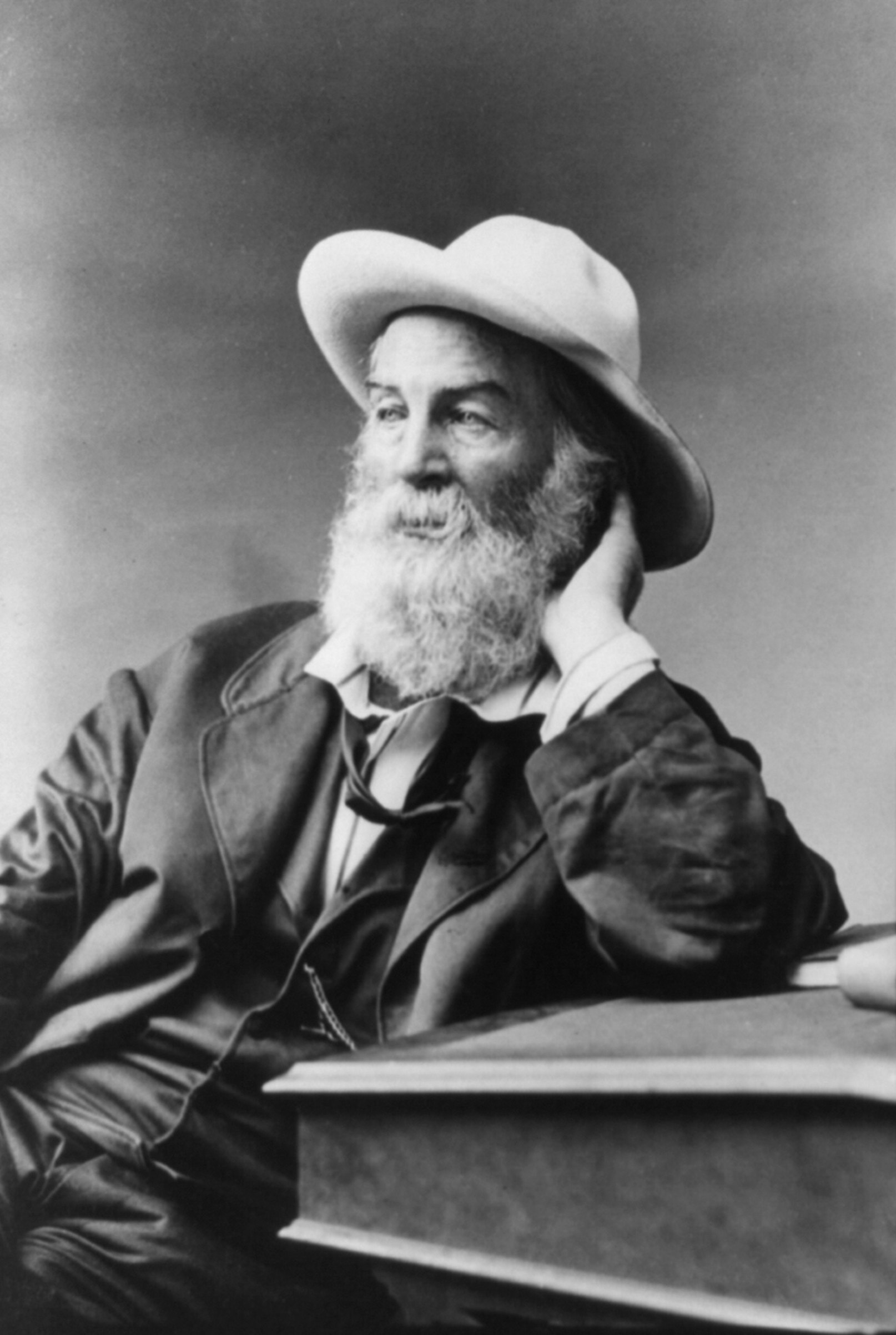

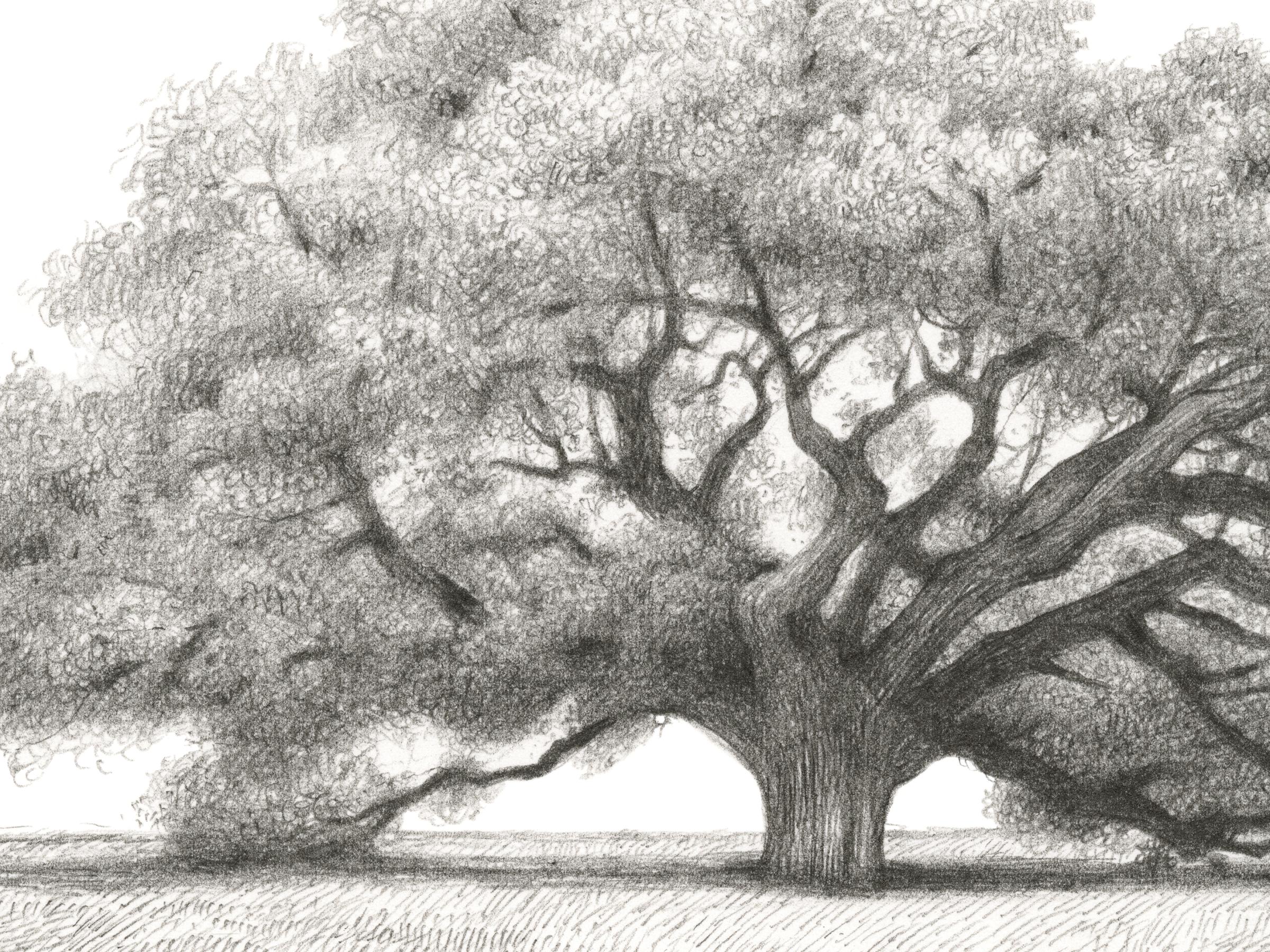

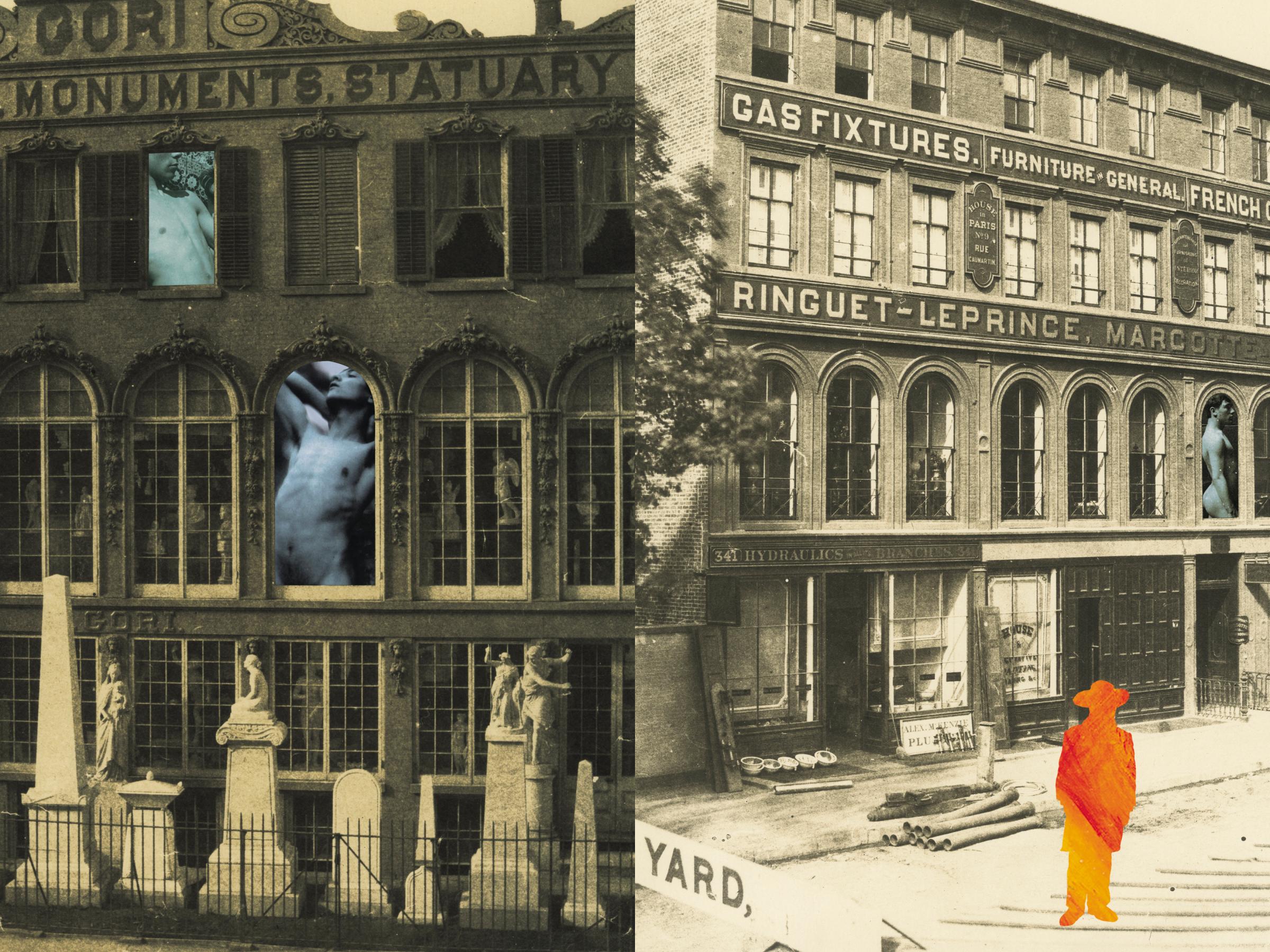

In the following selection from the afterword to a new edition of Live Oak, with Moss, a set of Walt Whitman poems rediscovered in the 1950s and now presented with illustrations by Caldecott Award-winning illustrator Brian Selznick — two of which are seen here, with two of the poems from the cycle — scholar Karen Karbiener explains the enduring puzzle of this forgotten work by one of America’s most famous poets:

As he was turning 40, Walt Whitman worked on 12 poems in a small handmade notebook he entitled “Live Oak, with Moss.” He later took the book apart, edited these poems and intermixed them with 33 new poems to create the “Calamus” cluster of the third edition of Leaves of Grass. Whitman never published the “Live Oak, with Moss” poems as he had written them in his notebook, and there is no record of his mention of them to even his closest friends.

The disbanded leaves of the 12 original “Live Oak, with Moss” poems were discovered by scholar Fredson Bowers, who published their contents in the scholarly journal Studies in Bibliography in 1953. But the poems did not gain serious critical attention from academics until the 1990s. Even now, more than 160 years after Whitman conceived the idea of “Live Oak, with Moss,” this revolutionary, extraordinarily beautiful and passionate cluster of poems remains largely unknown to the general public.

Yet they have immediate and powerful relevance for every reader who opens this book. For Whitman these poems were his first intense, sustained reflections on the love and attraction he felt for other men. For scholars they represent a new chapter in literary and social history: In these dozen poems, Whitman attempts to establish a definition of same-sex love decades before the word “homosexual” was in common parlance, and he dreams of a supportive community of lovers more than 100 years before today’s LGBTQ rights movement. Whether or not you know him and his work, whatever your sexual orientation and gender, you will find in these poems the timeless and courageous voice of a person attempting to be true to himself, body and soul. As we push open doors and start up conversations in this earnest, if conflicted, era, Whitman’s reassembled and newly interpreted “Live Oak, with Moss” serves as a personal guidebook and a source of inspiration.

The second of eight children born to barely literate, financially unstable parents, Walter Whitman Jr. was a grammar school dropout who learned to love language while setting type for Brooklyn’s booming print industry. The “signal event of my life up to that time,” he writes in his prose memoir, Specimen Days, was gaining access to the Brooklyn Apprentice’s Library, the city’s first free circulating library. Whitman must have felt at home in its collection of classic literature, travel and geography books: in the library’s tenth year and Whitman’s 16th, he was recorded as “acting librarian” of its 1,200 volumes. His self-led great books curriculum gave the budding poet something to shout about. “While living in Brooklyn, (1836–’50),” he continues in Specimen Days, “I went regularly every week in the mild seasons down to Coney island [sic], at that time a long, bare unfrequented shore, which I had all to myself, and where I loved, after bathing, to race up and down the hard sand, and declaim Homer or Shakspere [sic] to the surf and sea-gulls by the hour.” When the Brooklyn boy visited Manhattan, he delighted in opera and the theater, particularly “all Shakspere’s [sic] acting dramas, played wonderfully well.”

Whitman’s collection of poetry entitled Leaves of Grass is now recognized as America’s cultural declaration of independence, and he is regarded as America’s greatest poet and most original voice. It seems counterintuitive, even un-American, to think of him or his work as inspired by older European ideas of greatness. And yet the influence of Shakespeare stayed with him—not just for what the bard wrote but how he lived and worked. Preparing the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855, Whitman counted the number of words on a typical page of Shakespeare’s writings and strove to make his own word counts match. Whitman also took notes on Shakespeare’s biography, paying close attention to the parallels between them. He was intrigued that Shakespeare, like himself, was one of eight children, that he was a “handsome and well-shaped man,” and that by age 27 he “was already the father of three children—never seems to have amoured his wife afterward—nor did they live together.” His notebooks include descriptions of Shakespeare—“bargained, was thrifty, borrowed money, loaned money had lawsuits”; “did right and wrong . . . committed follies, debaucheries, crimes”—that seem to be echoed by the confessional narrator of “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” who “Blabbed, blushed, resented, lied, stole, grudged,/Had guile, anger, lust, hot wishes I dared not speak.”

Whitman saw in Shakespeare a model for a literary life, for better and for worse. Even more unusually, the so-called father of free verse was impressed by Shakespeare’s use of the sonnet’s restrictive form. “For superb finish, style, beauty, I know of nothing in all literature to come up to these sonnets,” he told his friend Horace Traubel. “They have been a great worry to the fellows, and to me too—a puzzle, the sonnets being of one character, the plays another.” Though he owned few books, he possessed an 1847 copy of The Poems of William Shakespeare that included the entire sonnet sequence and “The Rape of Lucrece,” prefaced with a passionate note from Shakespeare to the Earl of Southampton (“The love I dedicate to your Lordship is without end”). “Shakespeare wrote his ‘sugar’d sonnets’ early—probably soon after his appearance in London,” Whitman noted, adding that “the beautiful young man so passionately treated, and so subtly the thread of the sonnets is without doubt the Earl of Southampton.” He was impressed that the Earl “made Shakespere [sic] the magnificent gift of a thousand pounds—Southampton was nine years the youngest— the ancient Greek friendship, seems to have existed between the two.” Whitman’s enduring interest in the culture of ancient Greece inspired his use of a time-honored code word for same-sex love.

Caught up in the craze for identifying the real person behind the “Fair Youth” of Shakespeare’s sonnets, Whitman would surely understand our interest in finding him in his own writings. Is “Live Oak, with Moss” about Whitman’s affectionate and erotic relationships with his own versions of the “Fair Youth”? Is the narrator Whitman himself, as Walt and so many others have speculated of Shakespeare in his sonnets? It is difficult to not imagine Whitman himself as the voice of these intimate, impassioned expressions of self, and his secrecy about the poems invites us to consider his motivations for being so guarded. The narrator is, after all, a man (IV’s “brethren,” VII’s “his,” and VIII’s “other men” confirm it), a poet (II, V, VI, VII, XI) who, like Whitman, saw live oak trees in Louisiana (II). Yet it’s always a tricky business to con ate the author with his characters. Attempting a pure autobiographical reading of “Live Oak, with Moss” is as futile as trying to pin down Shakespeare as the “I” of his sonnets. Each and all of these poems resist straight- forward explications, defy our attempts to map out real relationships, and encourage ambiguity rather than resolution. Whitman seems to have followed Shakespeare’s lead in making a “puzzle” of his poems.

Selections From Walt Whitman’s Live Oak, with Moss

II.

I saw in Louisiana a live-oak growing,

All alone stood it, and the moss hung down from

the branches,

Without any companion it grew there, glistening

out with joyous leaves of dark green,

And its look, rude, unbending, lusty, made me think

of myself;

But I wondered how it could utter joyous leaves,

standing alone there without its friend, its

lover—For I knew I could not;

And I plucked a twig with a certain number of

leaves upon it, and twined around it a little

moss, and brought it away—And I have

placed it in sight in my room,

It is not needed to remind me as of my friends, (for

I believe lately I think of little else than of

them,)

Yet it remains to me a curious token—I write these

pieces, and name them after it;

For all that, and though the live oak glistens there

in Louisiana, solitary in a wide at space,

uttering joyous leaves all its life, without

a friend, a lover, near—I know very well I

could not.

VII.

You bards of ages hence! when you refer to me,

mind not so much my poems,

Nor speak of me that I prophesied of The States and

led them the way of their glories,

But come, I will inform you who I was underneath

that impassive exterior—I will tell you what

to say of me,

Publish my name and hang up my picture as that of

the tenderest lover,

The friend, the lover’s portrait, of whom his friend,

his lover, was fondest,

Who was not proud of his songs, but of the

measureless ocean of love within him—and

freely poured it forth,

Who often walked lonesome walks thinking of his

dearest friends, his lovers,

Who pensive, away from one he loved, often lay

sleepless and dissatisfied at night,

Who, dreading lest the one he loved might after all

be indifferent to him, felt the sick feeling—

O sick! sick!

Whose happiest days were those, far away through

fields, in woods, on hills, he and another,

wandering hand in hand, they twain, apart

from other men.

Who ever, as he sauntered the streets, curved with

his arm the manly shoulder of his friend—

while the curving arm of his friend rested

upon him also.

Adapted from Live Oak, With Moss by Walt Whitman, illustrated by Brian Selznick and featuring an afterword by Karen Karbiener © Abrams ComicArts, 2019.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com