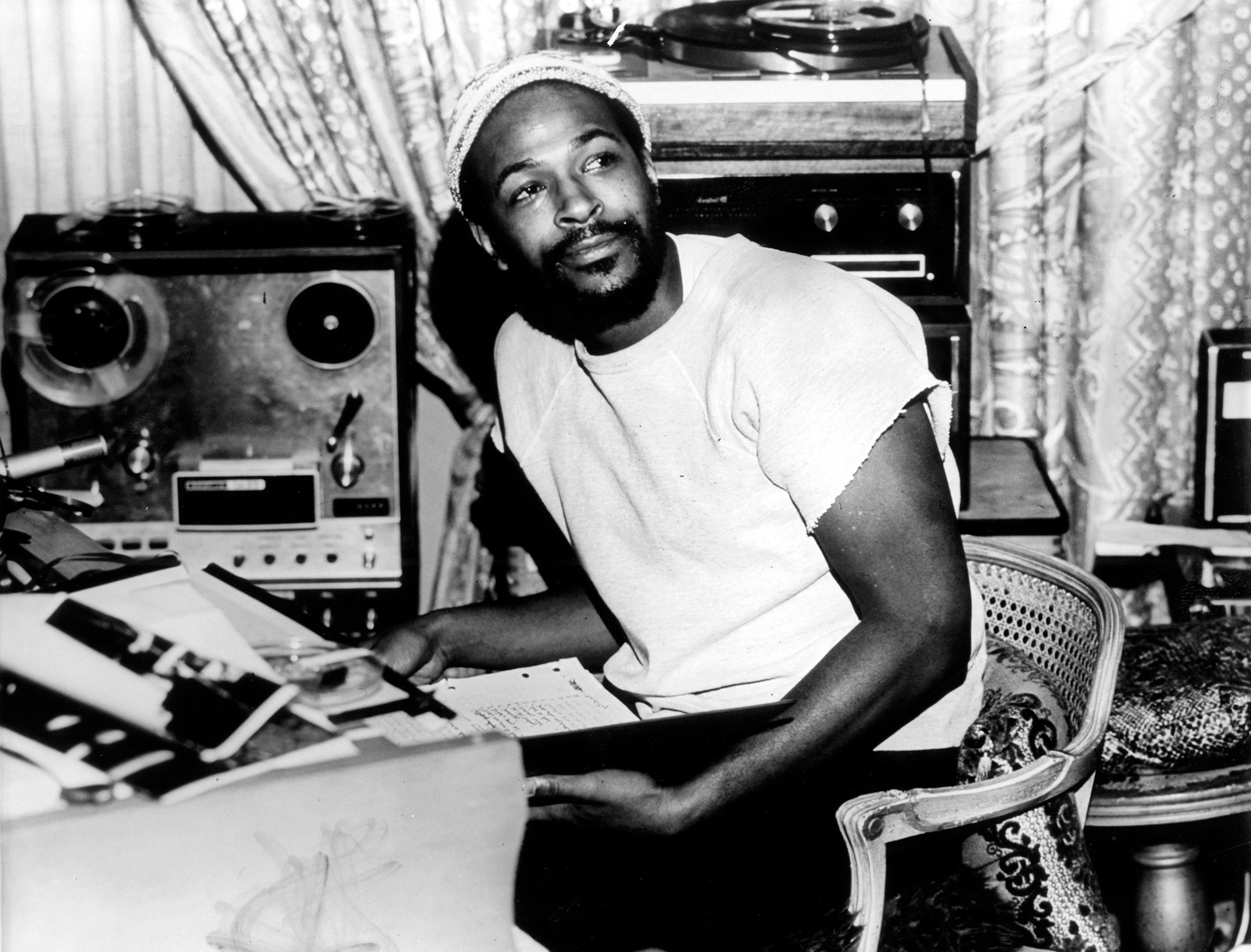

In 1972, Marvin Gaye seemed to be at the peak of his career. A year earlier he had released his album What’s Going On, a subversive, era-defining masterpiece. A year later he would release his next album, Let’s Get It On, the future gold standard for slow jams. But in between those creative pinnacles, Gaye, 32, fell apart. His marriage had crumbled, he was feuding with Motown, and he spent much of his time alone in Detroit, depressed and high. When his single “You’re the Man” tanked on the pop charts, Gaye’s confidence–and Motown’s confidence in him–went with it. The songs he recorded for a 1972 album were scrapped and never released as a whole.

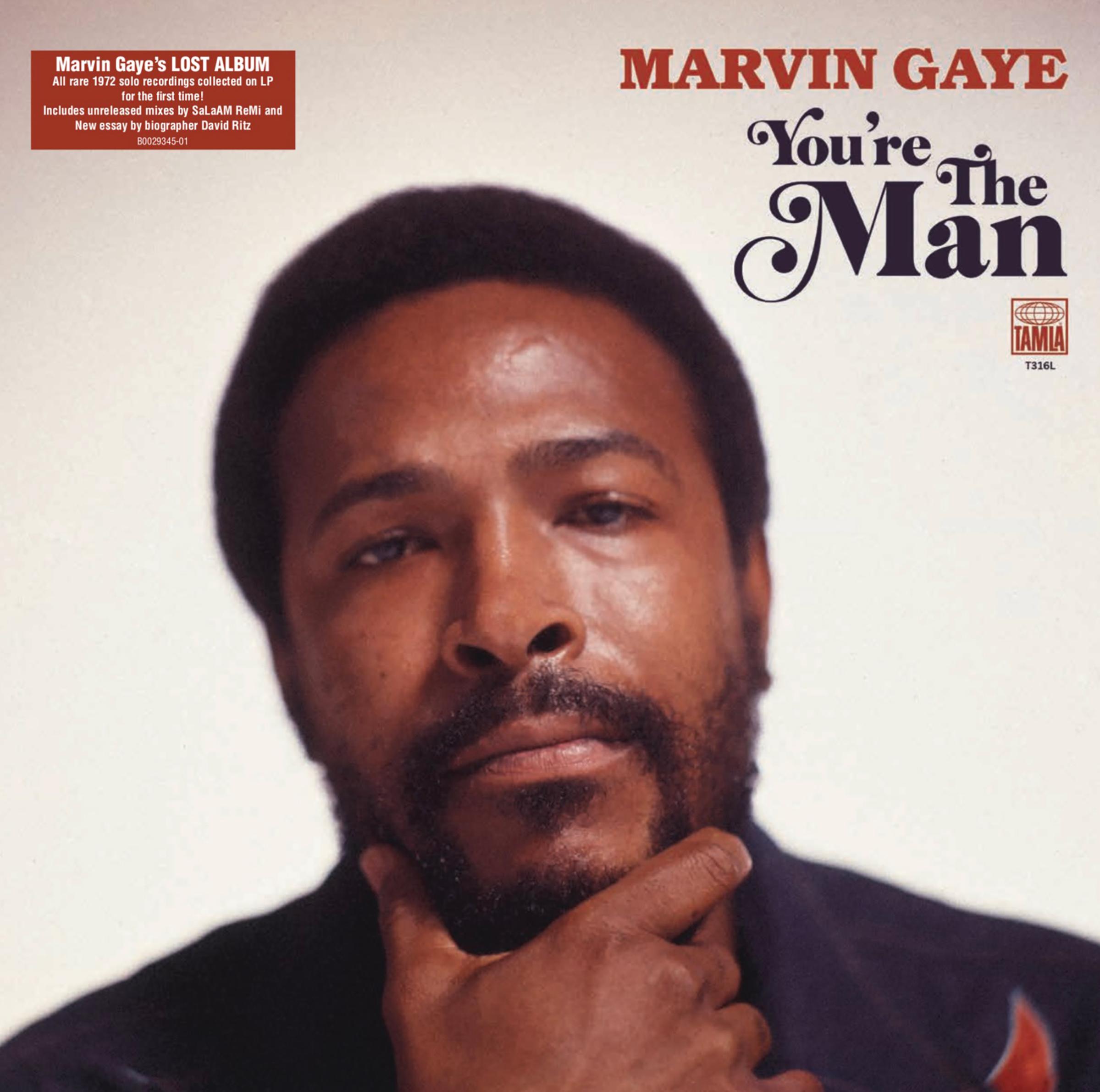

Until now. On March 29, Motown will release You’re the Man, which includes 17 songs mostly recorded during that chaotic year. The project shows a brilliant and tormented artist exploring themes that still resonate today, and reveals a potential dual path that Gaye would mostly abandon, in which he might have been both a symbol of sex and an advocate for protest, rather than doubling down on the former.

What’s Going On was a contemplative album that reckoned with inner-city poverty, environmentalism and war. Despite Motown president Berry Gordy’s hatred of the title track–and its stark departure from the label’s R&B-lite formula–it was a huge hit, captivating a counterculture pining for peace and equality. Critics began to treat Gaye as a serious artist.

Gaye was gratified by the success of What’s Going On but nervous about replicating it–he wanted to be more political on his next record. Unlike the lulling “What’s Going On,” “You’re the Man” demands policy changes over hard-charging funk. In the song, Gaye calls for a presidential candidate who would address desegregation busing, inflation and unemployment in the black community.

Leroy Emmanuel, who played guitar on the song and says he knew Gaye growing up, tells TIME that Gaye’s political evolution caused conflict with Motown. “He didn’t have a lot of people to talk about politics with,” he says. “Marvin was in another world, and a lot of his growth was stunted.” But the song performed well on the R&B charts, leading Motown to schedule an album. On the songs Gaye recorded for that release, he doesn’t back down: he gets existential about a country filled with “sidewalk sleepers” in “Where Are We Going” and sings “I Want to Come Home for Christmas” from the perspective of a somber Vietnam War POW.

As Gaye explored protest and advocacy, he also pivoted toward the erotic themes and funk aesthetics that would dominate his next wave of music. Trembling guitars and a cascading Moog keyboard propel ballads that call for sexual freedom. On “Piece of Clay,” he laments both carnal and geopolitical exploitation, placing them within the same struggle for liberation.

But while Gaye was fulfilled in the studio, the rest of his life was far messier. Motown was moving to Los Angeles, leaving Gaye feeling stranded. “You’re the Man” failed to cross over to white audiences. The album was called off. Various songs would end up on box sets and bonus editions. And instead of continuing to be a political messenger, Gaye mostly turned to themes of romance and heartbreak in his music until he was killed by his father in 1984.

It’s impossible to know whether Gaye would have wanted this work released posthumously. “He never wanted to discuss his death,” David Ritz, who interviewed Gaye for a 1985 biography, tells TIME. But this album complicates the narrative that Gaye forged a clean linear break between the political and the personal. You’re the Man is a snapshot of an artist in flux, commingling both with powerful results.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com