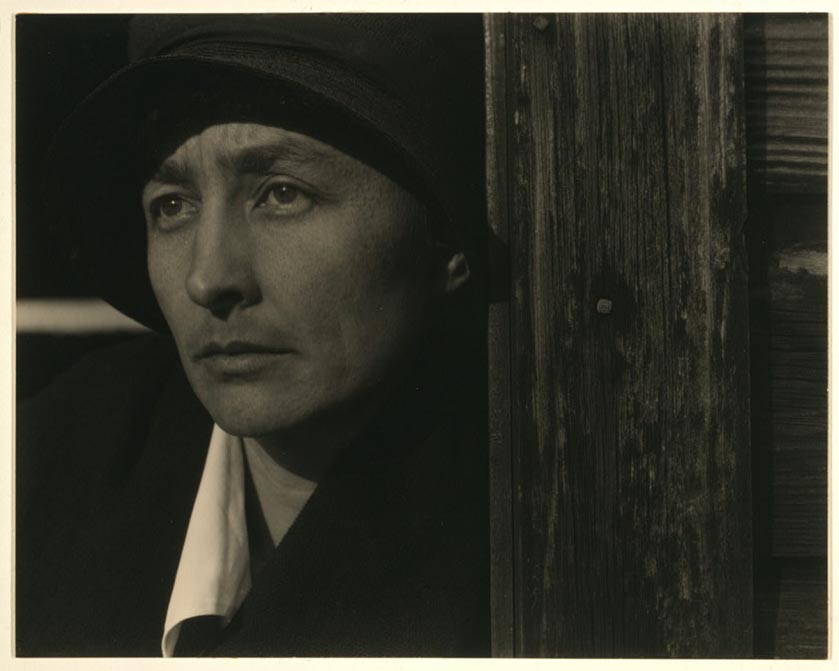

A never-before-seen collection of letters from American artist Georgia O’Keeffe and her husband, photographer and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz, sheds light on her artistic process, her quest for independence and her poetic observations about New York City and New Mexico — which became central to her iconic paintings.

The Library of Congress announced Thursday that it had acquired the collection of letters, written from 1929 to 1947, to the couple’s friend, filmmaker Henwar Rodakiewicz, making them public for the first time.

Barbara Bair, a curator in the library’s Manuscript Division, says the letters were written during a period in O’Keeffe’s life when she was spending more time in New Mexico, seeking out independence in her work and her marriage.

“We get both the exuberant Georgia, where she’s excited by the desert and starting to paint new things, like the skulls of cattle. She’s responding so well to the beautiful reds and oranges of the desert,” Bair says. “We get a lot of the feeling of expansiveness that she’s experiencing, that she’s broken free.”

O’Keeffe spent the summer of 1929 in New Mexico, establishing herself in a community of artists, painting the landscape and learning to drive in the desert. But the letters also reveal a more vulnerable side during the early 1930s, when O’Keeffe had a breakdown and was hospitalized for psychoneurosis.

“It’s also about self care,” Bair says. “When she is broken, what does she do to regain herself? She goes to beautiful places and feeds herself on the landscape and recovers.”

In a 1944 letter, O’Keeffe described the flat-topped Pedernal mountain in New Mexico that served as an inspiration for many of her paintings.

“It is hazy — and my mountain floats out light blue in the distance — like a dream,” she wrote, according to the Library of Congress.

She often claimed the mountain as her own, and her ashes were scattered there when she died in 1986. “It’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it,” she once said.

“Yesterday, you could see every tree on it and last night — I thought to myself — it is the most beautiful night of the world — with the moon almost full — and everything so very still,” O’Keeffe wrote in the 1944 letter.

O’Keeffe, a pioneer in modern art, became known for her vivid, large-scale paintings of flowers and bones in the desert landscape of New Mexico.

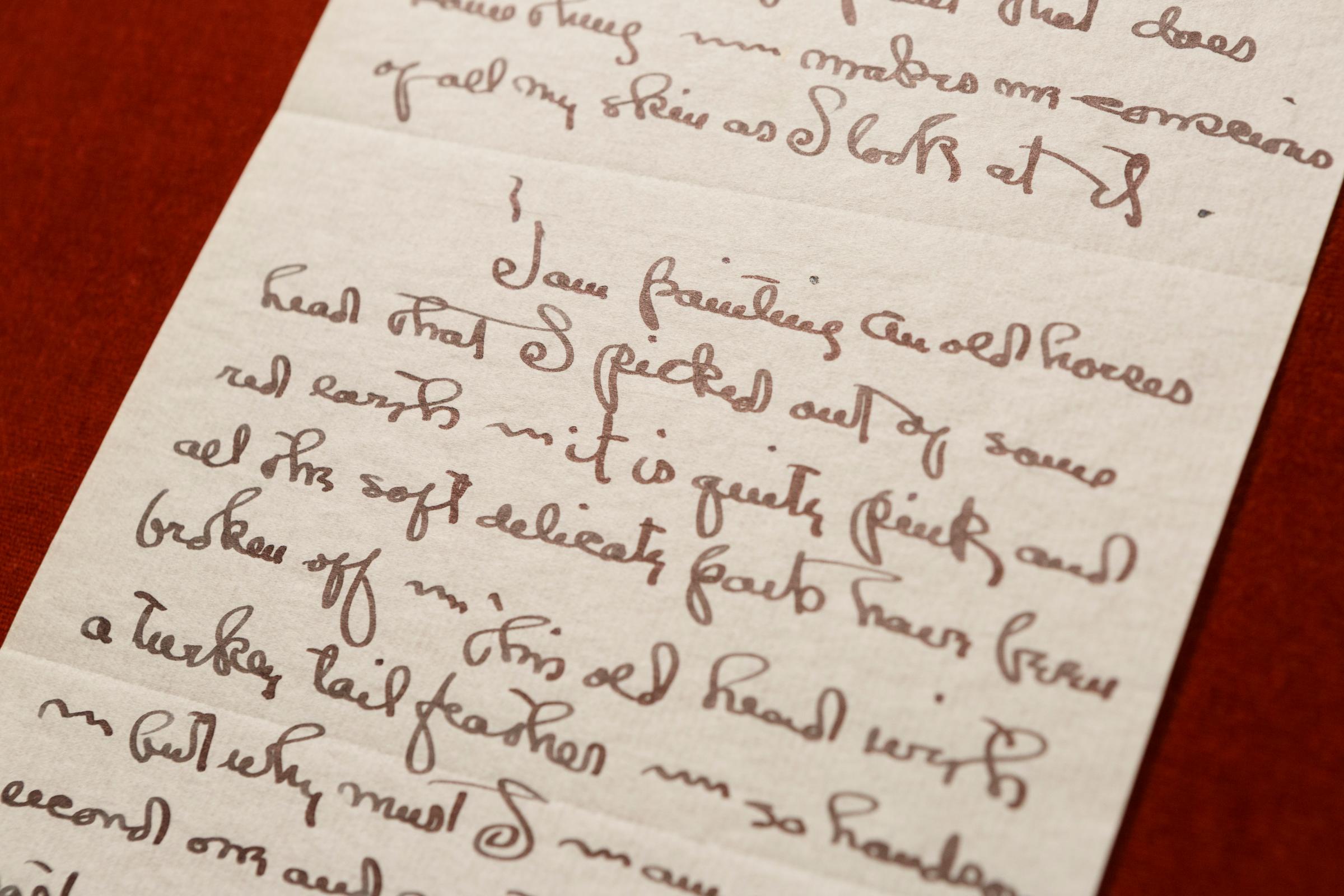

“I am painting an old [horse’s] head that I picked out of some red earth,” she wrote to Rodakiewicz from New Mexico during the summer of 1936, pictured below. “It is quite pink and all the soft delicate parts have been broken off — this old head with a turkey tail feather — so handsome — but why must I — am on my second one and must do it again at least once more.”

It is not clear which painting she was referring to in that letter, though several of her paintings depict the skulls of horses or cattle.

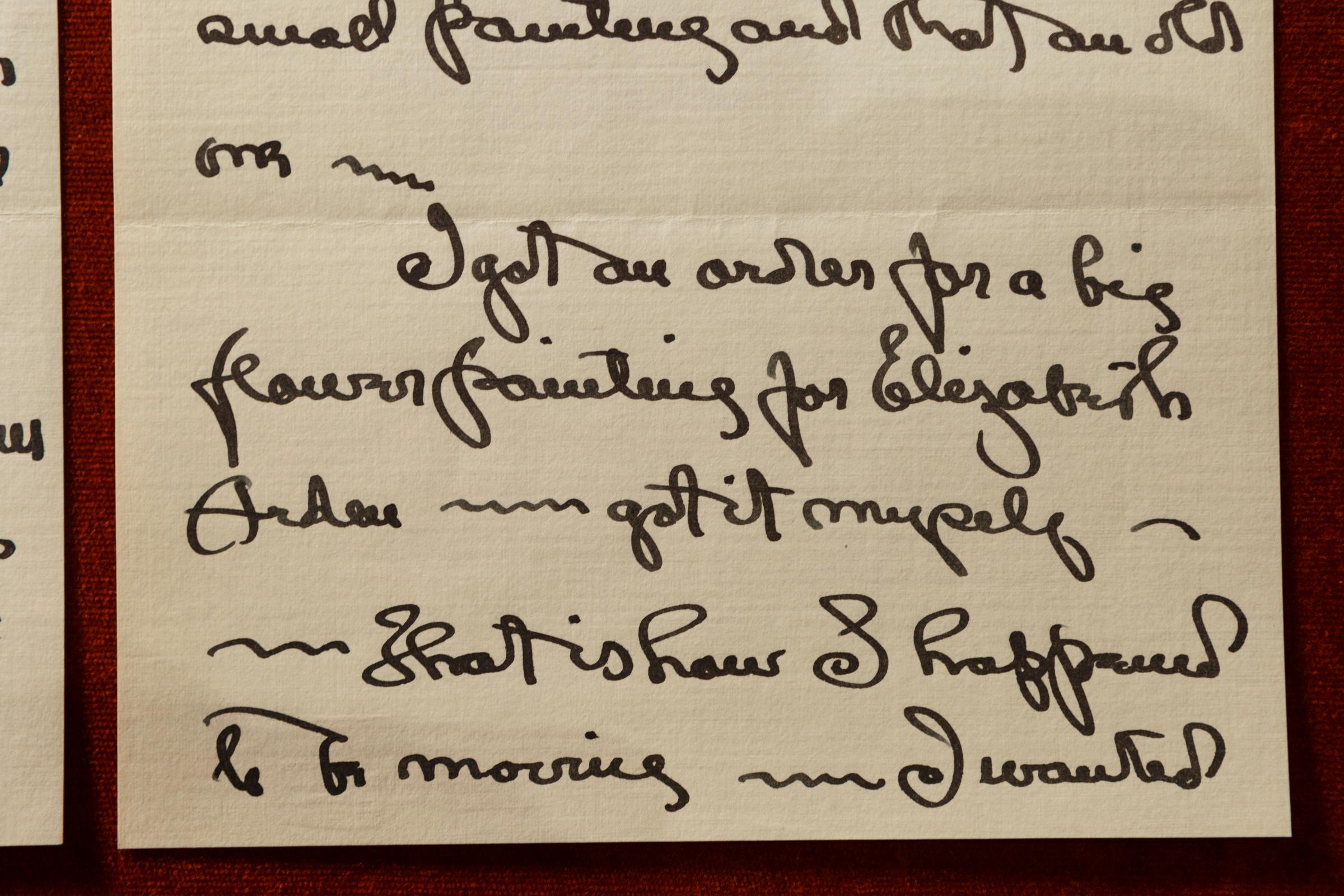

“I have moved to such a lovely place . . . all feeling free and open,” she wrote from New York in a 1936 letter to Rodakiewicz, pictured below. “I got very good notices for my show — sold only one small painting . . . I got an order for a big flower painting for Elizabeth Arden — got it myself.”

That 1936 painting, “Jimson Weed,” was commissioned by Arden, the beauty entrepreneur, for the exercise room of her salon in New York and is now on display in the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

At the time, Bair says, O’Keeffe was working hard to get her own commissions in order to gain more independence and separate her work from Stieglitz.

“Now I’ve got to get the painting done,” O’Keeffe wrote in the letter to Rodakiewicz. “Maybe I’ve been absurd about wanting to do a big flower painting, but I’ve wanted to do it and that is that. I’m going to try. Wish me luck.”

O’Keeffe returned again and again to “big flower paintings.” “When Georgia O’Keeffe paints flowers, she does not paint fifty flowers stuffed into a dish,” TIME wrote about her in 1928. “On most of her canvases there appeared one gigantic bloom, its huge feathery petals furled into some astonishing pattern of color and shade and line.”

In 2014, O’Keeffe set a new auction record for the most expensive work of art by a woman, when her 1932 painting, “Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1,” sold for $44.4 million.

The letters included in the Library of Congress collection reveal more about her friendship with Rodakiewicz, who kept the letters until he died in 1976. They were found years later in a house once occupied by his third wife.

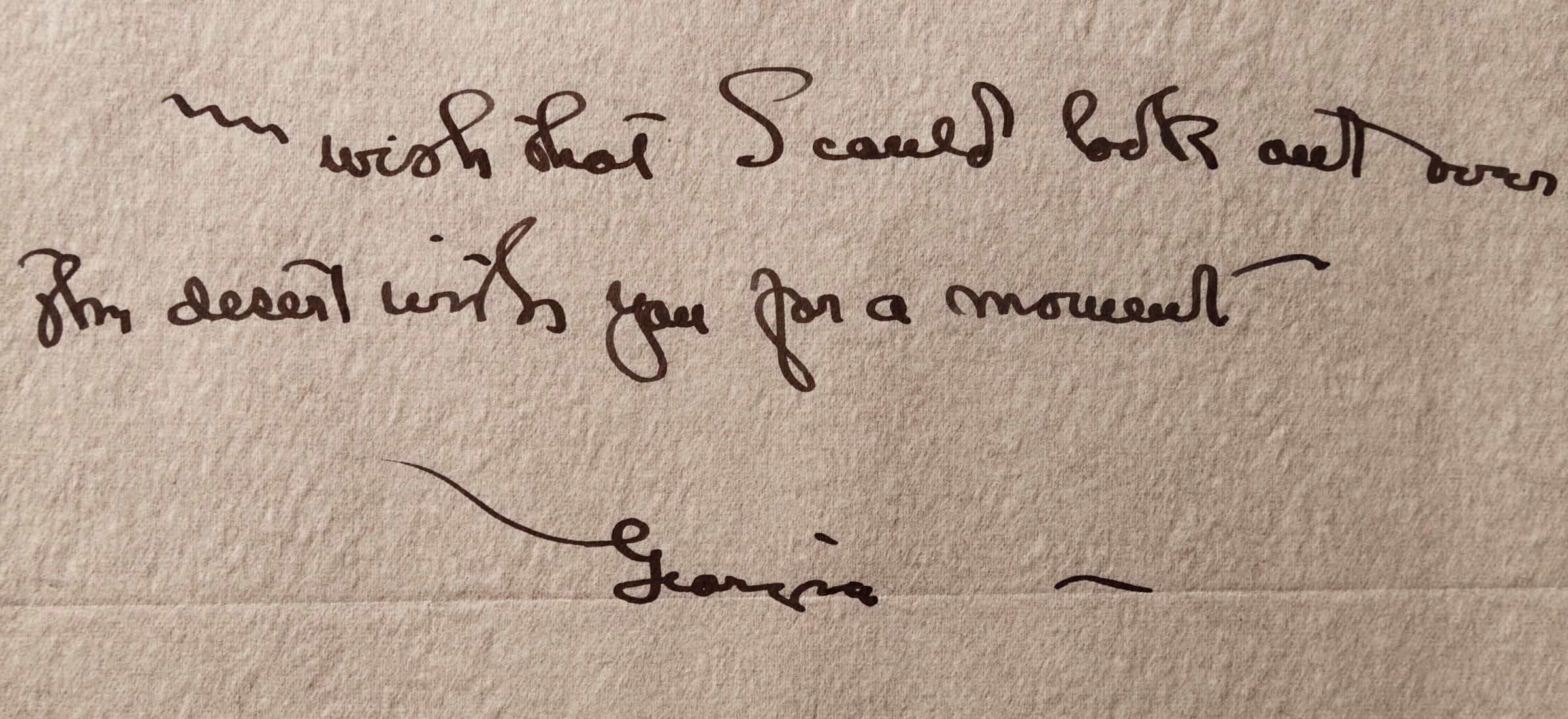

Bair says it’s not clear if O’Keeffe ever had a romantic relationship with Rodakiewicz. While she expresses love in the letters, she was often affectionate in correspondence with other people as well.

“It’s all in how you read them,” Bair says. “It’s difficult to know if it was actually consummated, but certainly they were very close, and she trusted him.”

“I’ve been a long time resting myself,” O’Keeffe wrote from New Mexico in a letter dated Dec. 1, 1939. “Wish that I could look out over the desert with you for a moment.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at Katie.Reilly@time.com