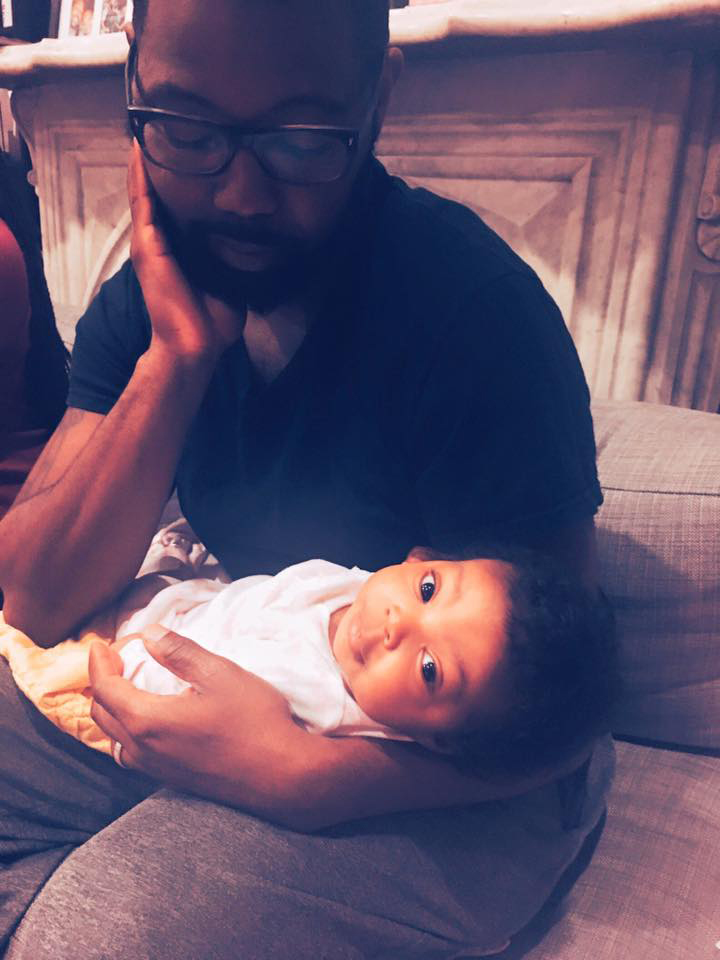

It was more than a year and a half after our daughter was born that I finally shared with my wife my thoughts from our first week as parents. After driving back from Home Depot, Alecia and I sat in the car for an hour so Zoe could keep napping in her car seat.

“You know, that first week, I was scared. I felt…I felt like…like she didn’t belong to us. Like ‘What are we supposed to do with her?’ I just didn’t feel like my life was worthy of taking care of hers. I felt…unqualified.”

While I waited for her to acknowledge me, it started raining. I was reminded of how, in High Fidelity, Rob Gordon was caught in the rain so often that it began to defy reason. Did he just chase torrential downpours for opportunities to emote?

And this is why, I thought, things like marriage and parenthood will always be uphill battles for me. Here we are, in the middle of this intimate moment, and I’m daydreaming about the moisture-retentive properties of John Cusack’s hair. Why can’t I just exist in the now? Even now – literally right now – I’m stressing over existing in the now instead of just existing in the now.

“Me too.”

“What?”

“I felt the same way. I was terrified. I think most new parents are, though.”

Throughout my life, the myriad anxieties and neuroses I carried would converge, aligning with each other to conspire against my common sense. And it usually worked. They’d convince me that I was the only one who experienced the doubt and angst I lugged around, tricking me into believing that my self-consciousness and the familiar diffidence it cultivated were singular. Because I’m black and male I’m not supposed to feel anxiety. I’m not supposed to feel doubt. I’m supposed to be cool, and that cool should be as effortless as Tracy McGrady jaunting back on D after hitting a hesi and laying a lefty jelly. I’d allow myself to feel — not believe, but feel — that I wasn’t who I was supposed to be.

I’ve grown progressively more confident that I am exactly who I’m supposed to be, but the belief that I’m somehow defective unmasks itself at inopportune times. Sitting in my car that day with my wife and sleeping daughter, I wondered how much better that first year and a half of being a parent would have been if I’d allowed myself to remember that other people are scared too. Although it would be wonderful if all the world’s angst and nervousness and restlessness and situationally inappropriate daydreams existed in one person, I am just not that special.

I am, however, terrified for Zoe.

I presume that as she grows older, the parts of me that are in her may grow more noticeable. I am also hopeful that her journey to accept and appreciate herself doesn’t last as long as mine did. But I don’t know how to pass on the good things without also passing on the bad. I want her to be observant and thoughtful, but not so thoughtful that she gives herself, as I have, acid reflux from the stress and anxiety that come from overthinking. I want her to regard new things with a healthy and safe skepticism that allows her to stay true to her convictions and not be as susceptible to peer pressure as many of her classmates might be. It’s an attribute that has served me well. But sometimes this reluctance to ignore my reservations and worries paralyzed (and still sometimes paralyzes) me, where my reticence and doubt congealed (and still sometimes congeals) into a lack of assertiveness and I ended (and still sometimes end) up not doing things I wanted (and still sometimes want) to do because I just couldn’t (and still sometimes can’t) find the will to be fearless. I want her to be too empathic to bully and humiliate people she’s bigger or smarter or cooler than, but if she ever has to compete — in sports, in school, wherever — I want her to possess the killer instinct that her dad never had. I want her to continue to be able to entertain herself and make herself laugh. But I don’t want her to be so lost in her thoughts and herself that she forgets to experience the now.

She’s also a little black girl and will eventually be a black woman in a world that is more dangerous for her than it has been for me. Alecia and I have already begun to think about how we’re going to teach her about race and racism and whiteness and white supremacy and racial profiling and police brutality and implicit bias. She will know what redlining and gerrymandering mean. She will be taught about how the lynching of black Americans was once such a mundane function of her country’s ecosystem that not only were postcards made depicting lynchings but they were sold during other lynchings. She will know that 1839 is both the date of the Amistad slave revolt and the home address (1839 Wylie Avenue) of Aunt Ester, the iconic matriarch in August Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean. She will know who Ruby Bridges was, and she will be taught before she is a teen that four little black girls not much older than her were killed in 1963 when their church was bombed by a racist. And if she ever attempts to discount that sort of racial violence as something from the distant past, she will be reminded that five months before she was born a terrifying 21-year-old white man sauntered into a South Carolina church and executed nine of its members.

Her hair is kinky and thick and nappy, and she will know that, if someone ever says those things about her hair, the proper response will be 'Thank you!'

She will also be exposed to Toni Morrison and Beyoncé. To bell hooks and Black Panther. To Octavia Butler and Ava DuVernay and Moonlight and Alex Haley and Chinua Achebe and Love Jones and Wu-Tang and Ruth Carter and Kara Walker and LaToya Ruby Frazier and both Smokey’s and D’Angelo’s “Cruisin’.” Just as our house is and will continue to be a living and breathing paean to black culture, black art, black language, black history, black food, black joy, black love and black people, her bedrooms will be museums of carefully curated blackness, brimming with black dolls and black figurines and books by black authors about black people, with little black girls like her on the covers. Her hair is kinky and thick and nappy, and she will know that, if someone ever says those things about her hair, the proper response will be “Thank you!”

She will know why there’s a small broom on the wall underneath a picture of Alecia’s and my wedding day, and she will know what “jumping the broom” means and where that act originated. She will be able to code switch, but she will never be pressured by her parents to do so. She will be taught the third verse of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which I didn’t even know existed until a year before she was born. She will eat (healthy-ish) soul food. I haven’t quite decided when an appropriate age for her to use nigga would be. But I want her to be comfortable with that word. I want her to eventually be a veteran nigga user. I desired meeting and marrying a woman I could nigga banter with. Now that I’ve found that, I look forward to providing nigga-use mentorship for our daughter. She will also know that her grade of blackness cannot be determined by how quickly she takes to Spades, how easily she learns to Wobble, or how interested she is in rap music. She will know that there’s no such thing as grades of blackness. She will know that she was born black, and there’s nothing she can do to not be black, and that if she chooses to do or be a thing — anything — that thing is officially “black enough” by virtue of her deciding to do or be it.

She will be taught that while black people have been victims of oppression, subjugation, bias and hate — and while we’ve faced these things for the hundreds of years we’ve been in America — blackness itself is not the problem. Her blackness is not a problem. It’s not her skin. It’s not her hair. It’s not the way she talks. It’s not the blood coursing through her veins. It’s none of the trillions of particles and elements that decided, through divine providence, to comprise her. She will be taught that whiteness needs blackness in order to possess and retain its value. She will learn that whiteness requires something it can claim itself to be better than. She will know that it needs that whipping boy and that bedtime story and that cautionary tale in order to sleep and to find a reason for waking. She will be told that the man who was elected president in 2016 was anointed because of whiteness’s urgent desire to preserve its supremacy.

Since whiteness was invented, blackness has been positioned as unseemly and uncivilized and demented and dirty. Blackness is to whiteness the puddle you attempt to avoid when crossing the street. And, if whiteness is feeling particularly ambitious that day, blackness is the puddle you place a jacket over so that other whites can step across it without being muddied. Perhaps, after learning this, she will be compelled to believe that blackness is the antithesis of whiteness. After nearly a half millennium of the nimble propaganda of white supremacy, it is natural and freeing and vindicating and deliciously petty to believe that whiteness is the source of all evil and blackness is the light. However tempting this is, I will remind her that while humanity can be sublime, if you are human, you are capable of evil. You are capable of oppressing. You are capable of everything the invention of whiteness has done to the people who have not been deemed white, and everything that inventing whiteness has done to the people deemed white.

Blackness forces you to love harder...It forces your hugs and your kisses and your daps to be tighter and longer, like a book you read ever so slowly because you’re not quite ready for it to end.

But she will also be taught that, because of this ceaseless racial antagonism, blackness allows her humanity to be amplified and evolved in a way both those who oppress and those who have benefited from oppression aren’t able to experience. Blackness forces you to love harder. It forces you to entertain the concept of forgiveness and choose whether it’s a thing you’re interested in possessing. It forces your hugs and your kisses and your daps to be tighter and longer, like a book you read ever so slowly because you’re not quite ready for it to end. It forces improvisation to be an immutable function of life. It forces you to seek solace and respite and community wherever they can be found, which makes you more cognizant of the world’s crevices and margins and ellipses and any other space where those twinkles of colony might be stashed. She will be taught, above all else, that she can be whoever and whatever she wants to be.

And this is where I have to stop, because this is where I’m stuck.

This is where, if she retains the things I will teach her, and if she continues to be as curious and as thoughtful and as intuitive and as quick and as skeptical as she currently is, she might eventually ask, “How?” How can she be whoever and whatever she wants to be if there’s a hulking and devious 500-year-old force constructed specifically to prevent her from doing that? How can she have a limitless future in the same America that killed the grandmother who died two years before she was born? How can all of those great things about her potential be possible — be true — if they exist at the same time this other thing, the other thing, does?

And I will have no choice but to be honest. “I don’t know.”

I don’t know how my little black girl can be all she can be when she can bounce in the lap of her grandfather, my dad, a man who is so much wittier and kinder and worldlier than so many of the white men who have been my teachers and lawyers and doctors and accountants and college basketball coaches but has never and will never experience the success and the status and the privilege that has come to them. Dad is 68 years older than Zoe, and the America he was born into is different from the one she was. This is true. The ceiling that lurked above him has been punctured.

But the ceiling is still there.

She is still in danger. She is still thought to be a threat. She will still have people assume she’s older and stronger and tougher than she actually is. She will still encounter nurses and doctors who’ll assume she doesn’t experience pain the same way little white girls do. She will still have her intelligence doubted, as if it’s not possible to be that black and also be that sharp. She will still have to watch racism and sexism join forces and attempt to pathologize her. She will still contend with the Chinese water torture of racial microaggressions. She will still exist in the same country, in the same state, in the same city, in the same neighborhood, and in the same classroom as people who will look at her sweet and brown and perfect little round face and see nothing but a nigger.

“I don’t know,” I will tell my daughter if she asks me how it’s possible to be all of the things I’ve told her she can be if America is all the things I’ve told her it can be. “But I know it happens, Zoe. I know it’s possible. I know you can and will be those things I said you can be.”

If the conversation goes anything like the conversations we have now, she will ponder what I said, nod her head and leave to go find another adventure to lose herself in. I will watch her scurry away, this miracle, and I will see Alecia. I will see Dad. I will see Mom. I will see me. And I will smile.

And then I will hope, and I will wish, and I will dream, and I will pray to God that she believed me.

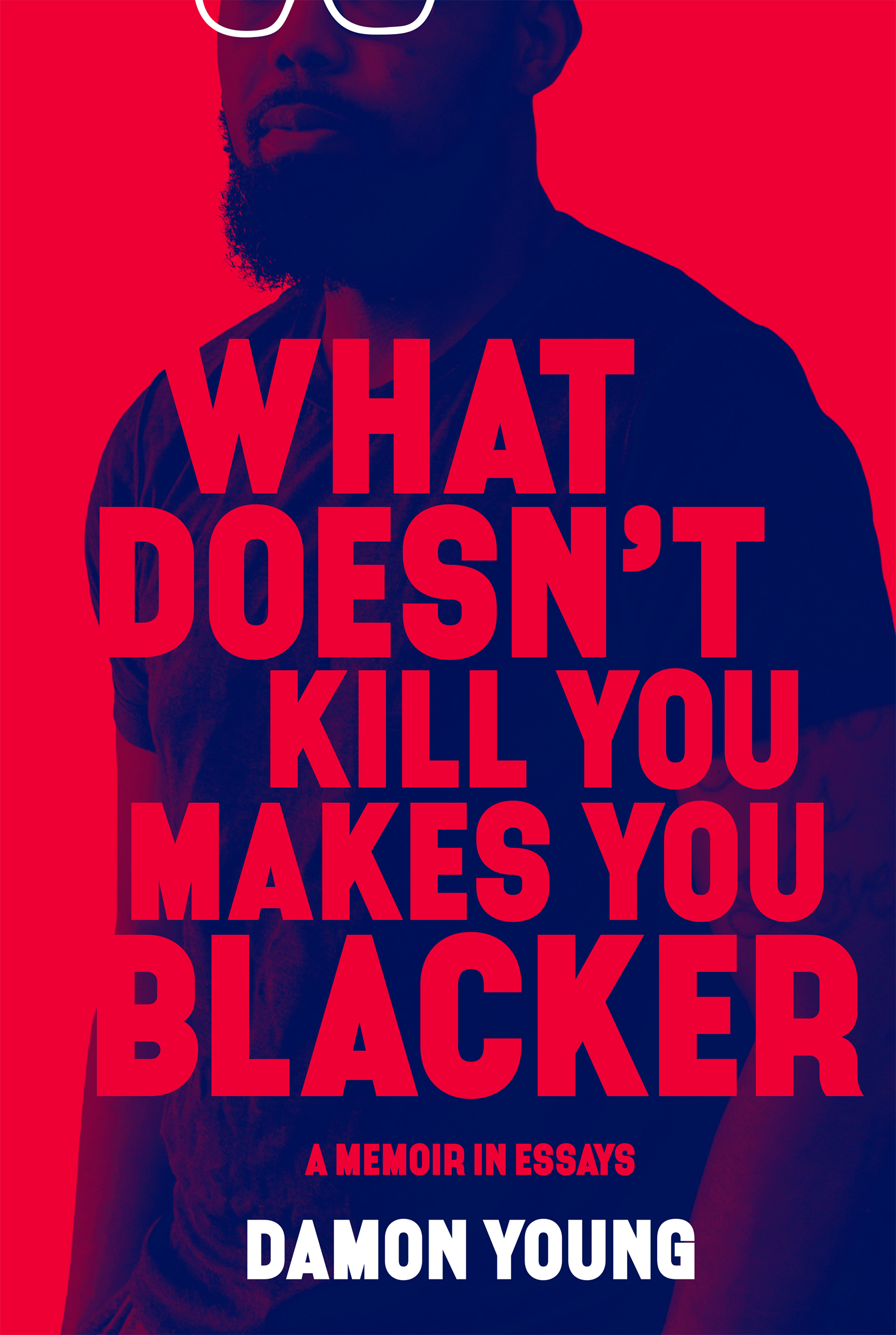

From the forthcoming book What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker: A Memoir in Essays by Damon Young. Copyright © 2019 by Damon Young. To be published on March 26, 2019 by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com