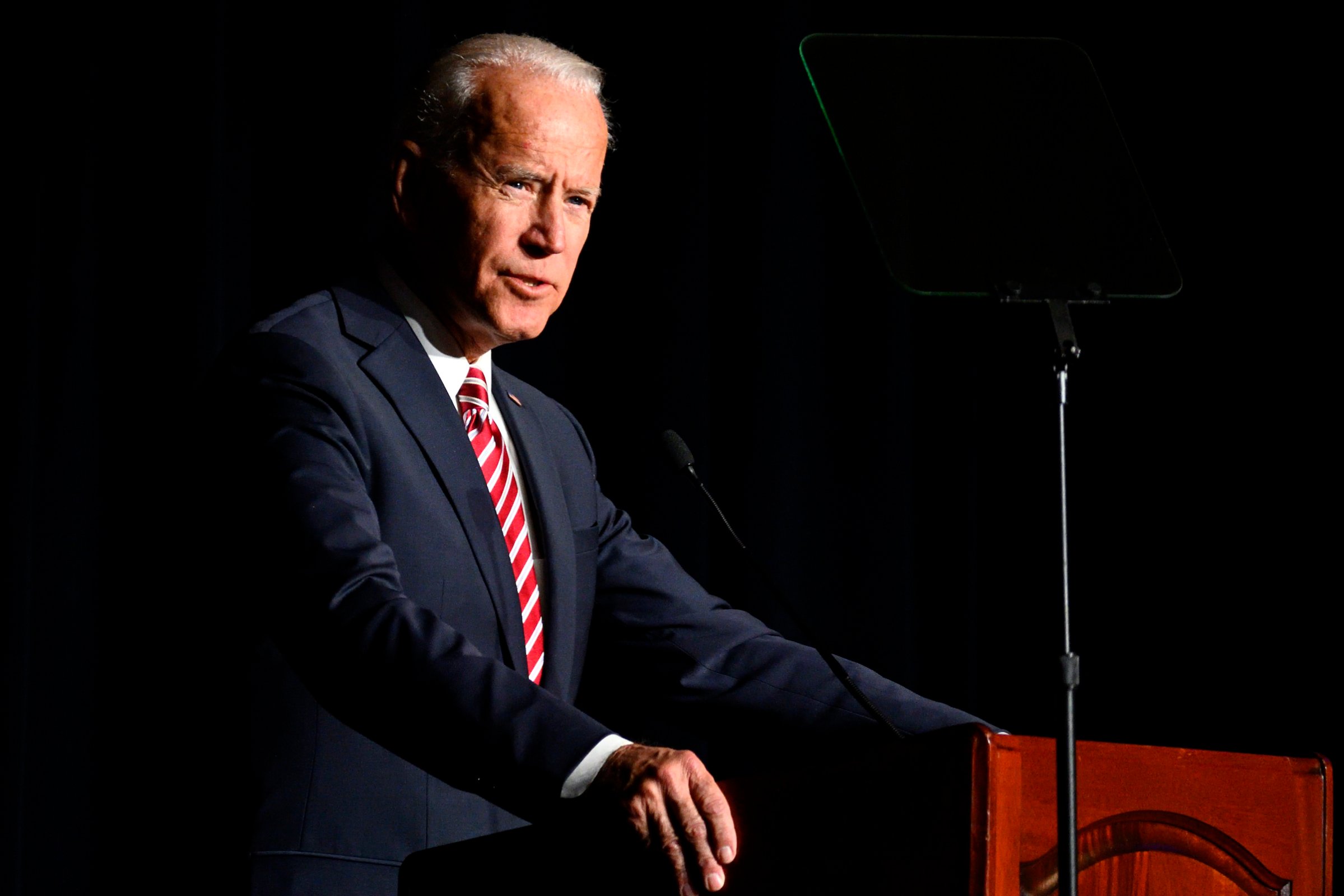

Capping off months of speculation and concern, the 47th Vice President of the United States Joseph R. Biden announced Thursday morning that he will join the 2020 race for the Democratic Party nomination for President. He thus joins a small club of people who have held the role of VP and made a run for the top.

And if Joe Biden is successful, he’ll join an even smaller club: So far in American history, Richard Nixon has been the only example of a Vice President successfully running for President after time has passed since he was Vice President.

Here’s what to know about where Biden’s run fits into that history — and how being VP can help and hurt a candidate — from an expert on the history of the vice presidency. Joel K. Goldstein is the author of The Modern American Vice Presidency: The Transformation of a Political Institution and The White House Vice Presidency: The Path to Significance, Mondale to Biden. He spoke to TIME in advance of Biden’s announcement.

TIME: What kind of historical parallels does Biden running for President in 2020 bring to mind?

GOLDSTEIN: I don’t really see a precise historical parallel. Nixon had run as a sitting VP in 1960 and almost beat Kennedy; then he runs for California Governor and loses. Then he makes a comeback and defeats a sitting Vice President, Hubert Humphrey. In 1984, Walter Mondale ran against a popular President [Reagan] who has much broader appeal than Trump did and Mondale had the baggage, the perception of 21% interest rates during the Carter administration. Then you have Dan Quayle who had abbreviated runs in 1996 and in 2000; in one instance he was sidelined by health problems but he really wasn’t getting much traction. But he and Bush had lost in ’92, so Quayle wasn’t perceived in the same way Biden is.

Biden is a former Vice President who served with a popular President — one who leaves office as a popular President — doesn’t run, and then runs four years later. And he has the unusual situation of his son’s illness and death, and the way he persevered. In modern times, if the President is popular, and even if he isn’t, the Vice Presidency tends to be a stepping stone. It was for Nixon, though that was a different nominating system.

How did the change in the process for nominating presidential candidates impact a former Vice President’s ability to run for President?

Before 1972, the nominations on both sides were pretty much controlled by party leaders. So in the world in which Nixon ran in ’60 or Humphrey in ’68, they were nominated not because they did well in the primaries or the caucuses, but because they were popular among party leaders who controlled state delegations. But that whole system changed in ’72, so it makes the Vice President more challengeable.

It sounds as if you’re saying the distance between Nixon’s time as Vice President and the time he was elected President in 1968 may have helped him.

I think that was one of the things that was helpful for Nixon, having the time [so] he can present himself as not just Eisenhower’s number two. But the Julie [Nixon]-David [Eisenhower] romance during the campaign brought back the Eisenhower ties in a way that was probably helpful to Nixon. And then there’s the disaster of the Vietnam War, and the fact that the Republican party is sort of split and Nixon runs as a centrist who can unite the party.

It’s hard for a party to win three straight times, a problem faced when a Vice President is running immediately to succeed the President he or she serves with. You’re limited. You can’t very well criticize, or it’s hard to set yourself apart from the President, hard to position yourself as a leader. When a former Vice President runs after a gap during which the party has been thrown out of office, like Mondale in ’84 and Quayle in ’96, there’s a certain amount of baggage since the administration is viewed negatively. Biden doesn’t have that problem since he and Obama left office very popular and Biden never sacrificed his brand as Vice President.

How do Vice Presidents who run for President typically fare?

The office has changed so much [since] Chester Arthur and Garret Hobart. If you ask how do [vice presidents’ presidential campaigns] normally turn out in history, well, then the statistic is that 14 Vice Presidents have become President. Nine became President by succession — eight after the deaths of Presidents, and one after a President resigned — and four sitting Vice Presidents were elected [John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Martin Van Buren and George H.W. Bush]. Nixon was a non-sitting Vice President who got elected.

If you combine the four sitting vice presidents who were elected president and Richard Nixon in 1968, a former vice president who was also elected, five vice presidents first became president through election in addition to the nine who succeeded to the office following the death or, in one case, resignation of their predecessor. In addition, in recent times three other sitting vice presidents — Nixon in 1960, Hubert Humphrey in 1968 and Al Gore in 2000 — lost in very close races.

The statistic that only four out of 47 vice presidents ran and were elected when they were sitting vice presidents is really misleading because a bunch of vice presidents die and a bunch get blocked by incumbent presidents who ran for re-election and lost, so it wasn’t really possible for the sitting VP to be elected, [for example] Hoover-Curtis, Carter-Mondale, Bush-Quayle. (With Pence, there have been 48 vice presidents, although he hasn’t had a chance to run.) So it’s not really fair to say a lot of sitting Vice Presidents don’t get elected because a lot of times they don’t really have a chance to run. I think the Vice Presidency is the best stepping stone, but it’s not a guarantee.

What qualities of the vice presidency make it easier or harder for someone in that position to run for President?

The office has changed a lot. Vice Presidents are doing a lot of political events, traveling over the country, all over the world, and becoming really involved in national security matters. The political role comes with visibility. You look at when Biden’s a Senator — the number of people who don’t have an opinion or don’t know anything about him is pretty high. Nixon in the 1950s saw the Vice Presidency as a way he could move forward. Eisenhower wanted to be above politics, so Nixon was the political guy who really leveraged it. Since Mondale became part of presidential decision-making and a close presidential advisor, Vice Presidents have gotten used to dealing with policy and making choices in a pretty serious way.

If a Vice President serves with an unpopular president, they inherit the baggage of that term. That’s a problem Hubert Humphrey had in ’68 [over the Vietnam War] and that Mondale had in ’84. Ronald Reagan could run against Mondale and blame him for 21% interest rates under Jimmy Carter and for the Iran hostage crisis. The other problem of being a sitting Vice President who runs for President is you’re perceived as the number two. When people look for a Presidential candidate, they want to see a number one.

Emerging from the shadows isn’t as much of a problem for a former Vice President. Vice Presidents go from being number two to the President, to being the leading figure of party who is eligible to run next time. Nixon runs in ’68 with experience as a statesman other people didn’t have.

Are there any myths or misconceptions about the vice presidency’s impact on a candidate’s chances?

People will say, “Biden has run twice before and he hasn’t done well.” But that’s true of a lot of people. Lyndon Johnson lost the race for the Democratic nomination for president in 1960. Then he [is picked to be John F. Kennedy’s Vice President and] becomes President by succession and wins in a landslide in 1964. The springboard benefit of being VP is really considerable. I imagine if you asked the Democratic presidential candidates whether they would rather be running as a former Vice President or a Senator or former Governor or former member of Congress or a former mayor, I think probably every one of them would say the Vice President.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com