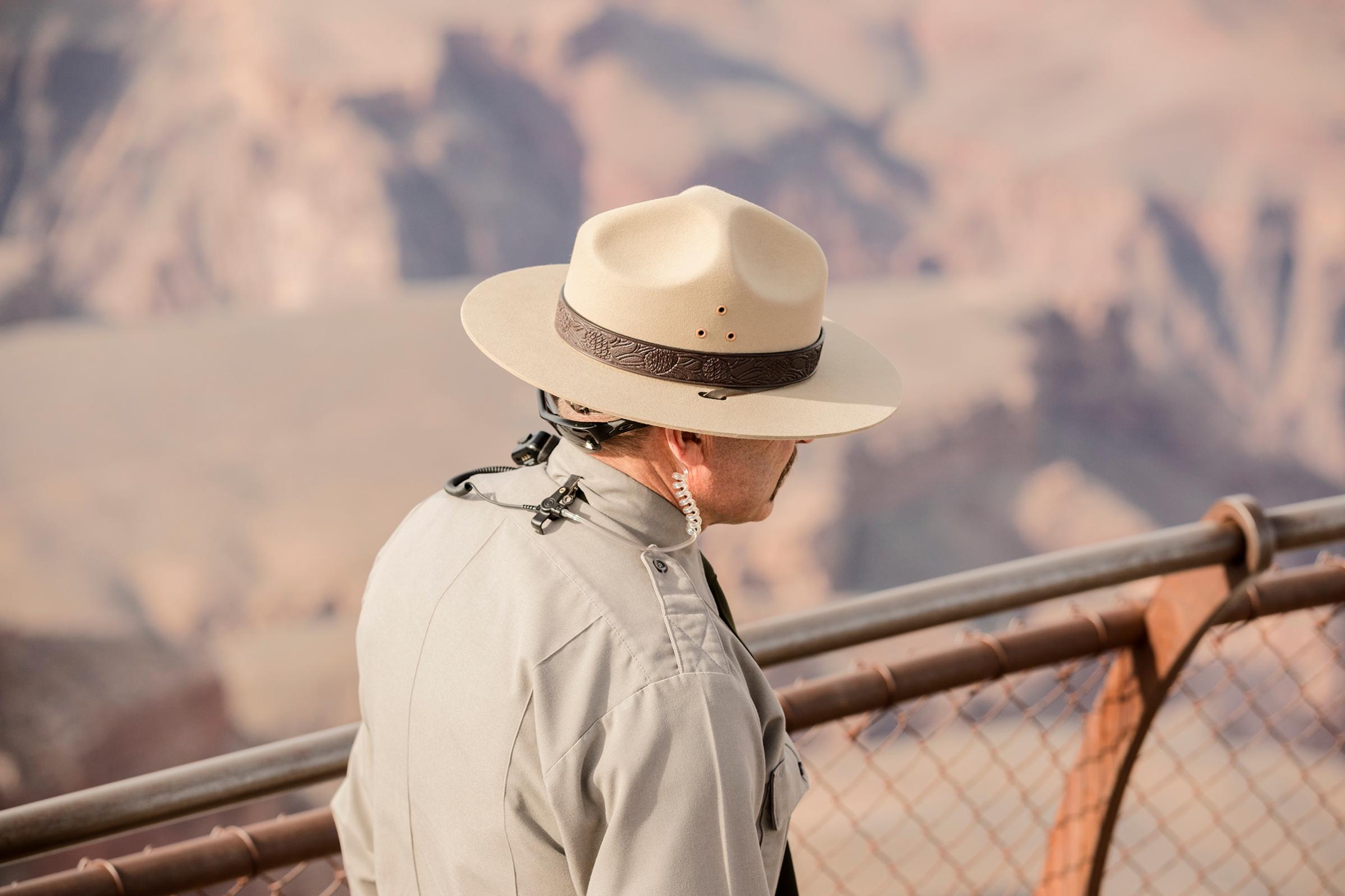

If you want strangers to ask to take a photo with you, walk around in a park ranger’s uniform. As chief ranger at Grand Canyon National Park, Matthew Vandzura knows this well. Even on a winter day, with snow on the ground and only a few dozen tourists at the popular Mather Point outlook, the jovial keeper of the canyon is in high demand. Hardy juniper clings to the ancient rock, a blue-black raven soars above the majestic chasm, and selfie sticks point like fingers toward the open Arizona skies as Vandzura, 51, smiles for snap after snap. On busier days, it’s normal for a line to form.

His celebrity may be local, but that spotlight has been shining a little more brightly lately, with the centennial celebration of the Feb. 26, 1919, signing of the act that created Grand Canyon National Park. Of course, the canyon itself is much older–to the tune of maybe 6 million years–so a hundred might sound small. But its place as a national institution is grounded in that moment, and what it looks like after the next 100 years is, in part, in the hands of people like Vandzura, who care for the land America has decided is most worth caring for.

“Our primary responsibility is preservation of the park in a way that allows people to enjoy it,” Vandzura says, paraphrasing the 1916 law that established the National Park Service (NPS). They provide opportunities for recreation, he says, “but in a manner that preserves things for future generations.” At the canyon, those current and future generations are a lot bigger than Teddy Roosevelt could have imagined when he issued his 1903 plea to “keep this great wonder of nature as it now is.” A record 6.38 million people visited last year. “It’s well known that Americans love their national parks,” Vandzura says. “We’re a culture that likes the idea of wide-open spaces.” But that appeal presents a challenge: how to keep natural beauty intact, and visitors in awe, even amid the crowds.

Vandzura doesn’t have a distinct memory of the first time he saw the canyon. But he was 15, on a family road trip, and he remembers the “immensity” of it. It was on that vacation that he decided to be a backcountry ranger, a goal that took him from a summer gig at a campground in 1988 to jobs including a stint as a seasonal firefighter at Arkansas’ Buffalo National River to a period in urban law enforcement at the St. Louis arch. He landed at Grand Canyon, for the second time, in late 2015.

Here, he faces the question of how to modernize an ancient natural wonder. An education campaign about safe hiking has already reduced the need for search-and-rescue missions. A smart parking system is being designed, a major advance for a village that was built for wagons. Vandzura wants to work even more closely with the Native American communities that call the area home, and convey to tourists that they can take their dollars to the reservations too. An app to reach visitors with such information is in development, though cell service in the park is limited; possibly bringing fiber optic to Grand Canyon Village is also being considered.

The staff is “dedicated to trying as many things as we can before we limit visitation,” Vandzura says. But they do talk about it, “when it’s August and all the parking spaces are filled and people are literally just driving in circles.”

And all this is only what Vandzura says constitute micro-level problems. The macro challenges for the next 100 years include everything from uranium mining in the region to management of the dam that controls the flow of the Colorado River through the park. Scientists predict that national parks will, on average, see the impact of climate change more severely than the rest of the U.S. And as the American Southwest faces water shortages, the question of how to both nurture and make use of the river will only become more urgent.

The Grand Canyon exists on the scale of deep time, and little we humans do can change it; the Grand Canyon exists today and the choices people make will affect its future. Reconciling these two truths can be difficult. But this is a place that has always tested the mind’s perspective. That’s why the park offers visitors mirrored panels called reflectoscopes, used by landscape artists to focus on just a slice at a time of an overwhelming vista. Without some remove, the view is unfathomable. “The common reaction from friends and family,” Vandzura says, “is that it doesn’t look real.”

But the mile-deep canyon is very real. And in many ways, taking care of it is just like any job. Back at headquarters, in his spacious but utilitarian office, Vandzura acknowledges that problems facing other industries face the park too. That includes a reckoning with workplace sexual harassment: a shattering 2016 report exposed abuses among park staff who worked the river at Grand Canyon. In the years since, NPS has reworked its antiharassment policy. Separately, park superintendent Christine Lehnertz, who has been seen as a champion of antiharassment measures, was recently investigated for accusations of “bullying and retaliatory behavior,” particularly toward men. A March 5 inspector general’s report found “no evidence” supporting the claims against her.

Vandzura is proud of the progress made, although he knows there’s still work to be done. “Our people are more important than our resources,” Vandzura says. “If you have to decide, you take care of people so you can take care of the mission.” Taking care of people doesn’t just mean worrying about the rangers on his crew. About 3,000 people live between the South Rim and the nearby town of Tusayan–Vandzura and his wife, a retired nurse, included–and the NPS is essentially their only government. That means being chief ranger is like being a small-town police chief. “We have the same problems in our community that any small town in America has,” Vandzura says, although those problems are filtered through the thin air of the canyon, where isolation means a lack of formal support systems.

That duty to the community was apparent during the recent partial government shutdown–the sixth Vandzura has weathered. The park itself stayed open; Arizona law allows the state to donate money to ensure as much, in recognition of its vital economic role. Vandzura says that, because he’s required to have funds in hand before keeping operations going, a member of Arizona Governor Doug Ducey’s staff drove out to meet him on a Saturday with a physical check. Even so, he estimates that more than two-thirds of staff stayed home, and a local pantry distributed 30,000 lb. of food while it lasted. Toilet-paper consumption was used to figure out that more people than usual visited during that time, but rangers couldn’t welcome them, scientific studies paused and maintenance lagged.

So, like any job, work here can sometimes feel like a slog. The difference is the cure. When it stops feeling like “the adventure they promised me in the back of the Boys’ Life magazine,” Vandzura just spends some time admiring the scenery he’s there to protect. Unsurprisingly, the Grand Canyon can make a person’s problems seem small. You see that, given enough time, even rocks and rivers change.

“We are a little blip in geologic time. You still need to do good work for the people who surround you, but it helps put things in perspective,” he says. “Even though it’s empty space, you can still sort of feel it when you’re by yourself out on the edge.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com