On Sunday, the 2019 awards season will reach its peak with the 91st Academy Awards, crowning last year’s film royalty. These celebrities will trot along the walkway that we know as the red carpet, a symbol of Hollywood’s glitz and glamor.

But the history of the red carpet is more complex than rolling one out for an event might be.

Still, over the span of multiple centuries, this carpet has found its way around the world and into American cultural conscience as a symbol of royalty and high status. Here’s how we can trace the history of this crimson carpet through time — and how it landed in Hollywood.

A Greek Tradition… Or Not?

A line in Agamemnon, the 458 B.C. play by Greek writer Aeschylus, is the first known reference to the glamorous practice of rolling out a red carpet. Because of this, scholars, historians and reporters have long pointed to it as the custom’s rightful origin. However, though the play describes a king (the eponymous mythical character Agamemnon) returning home after winning a battle upon a “crimson path,” this wasn’t actually a custom in Aeschylus’ world, according to Richard Martin, a professor of classics at Stanford University.

The line positions the red carpet as a means of transporting someone royal from the chariot to the home. “Now my beloved, step down from your chariot, and let not your foot, my lord, touch the Earth,” the play reads. “Servants, let there be spread before the house he never expected to see … a crimson path.”

It might not sound different from the vision of transporting a star from limo to theater, but carpets played no role in contemporaneous Greek culture, according to Gregory Crane, a classics professor at Tufts University. The idea may have been introduced to Aeschylus from someplace else. “‘Rolling out the red carpet for royalty’ seems to have been an old custom in the Near East,” Crane wrote in “Politics of Consumption and Generosity in the Carpet Scene of the Agamemnon.”

But Agamemnon is afraid to step on that red carpet, says Jeanne Gutierrez, a senior fellow in women’s history at the New York Historical Society. Red was such a special color, in fact, that it was almost deemed inappropriate for a mere mortal to stand on it. “He was hesitant to step upon it because red in ancient Greece was considered a divine color,” Gutierrez tells TIME. “Even though he was about as triumphant as a mortal man can get at that moment, he was still very concerned to step on this crimson path because it was considered for the gods only.”

Crane and Martin’s claims raise a question: Why would Aeschylus roll out the red carpet in his play? Scholars posit that the iconic red shade was more important than the carpet part — though it set off a custom that would spread throughout centuries and continents.

Red Is Royal

The Greeks weren’t the only ones who revered the color red as something belonging to royalty. Red has been the color of royalty for ages, according to Gutierrez. At the end of the 1200s, the Pope decreed that only cardinals, the highest-ranking men of the Catholic church, could wear red. Political figures took on their own version of this idea around the same time and leaders throughout Europe started incorporating red into their wardrobes. “They also start to wear red robes as a sign of their high status,” Gutierrez says. Beyond Europe, the Aztec and Inca cultures of Mesoamerica considered red “a color that would only be worn by the elite, the aristocracy,” Gutierrez says.

The association had one practical reason at its core: the price of red dyes before the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century. “Prior to the invention of synthetic dyes,” she explains, “red is an extremely difficult and expensive dye stock, and so red textiles are incredibly expensive, and they’re a sign of very high status because only a certain number of people can afford to wear them.”

In fact, in the 15th century Italian silk industry, both Venice and Florence passed laws to prevent sellers from deceiving customers by using cheaper dyes to feign more expensive fabric.

It’s not just expensive fabric, though. The shade also has religious connotations, and has long symbolized martyrdom and sacrifice in the Catholic church, Gutierrez says.

An Industrial Revolution For Red (and Carpets)

The price of red dye began to decrease in the 16th century after Spain conquered what is now Central and South America, Gutierrez explains. The Spanish took red dyes — made by the crushing of female cochineal insects — and sold them across Europe. “Eventually, it becomes such a valuable commodity that competitors start to get into the market,” Gutierrez says. Other colonial powers began to produce these insects to sell the dye.

Once the red dye was acquired, the carpets themselves were pretty expensive, too, needing to be hand-woven.

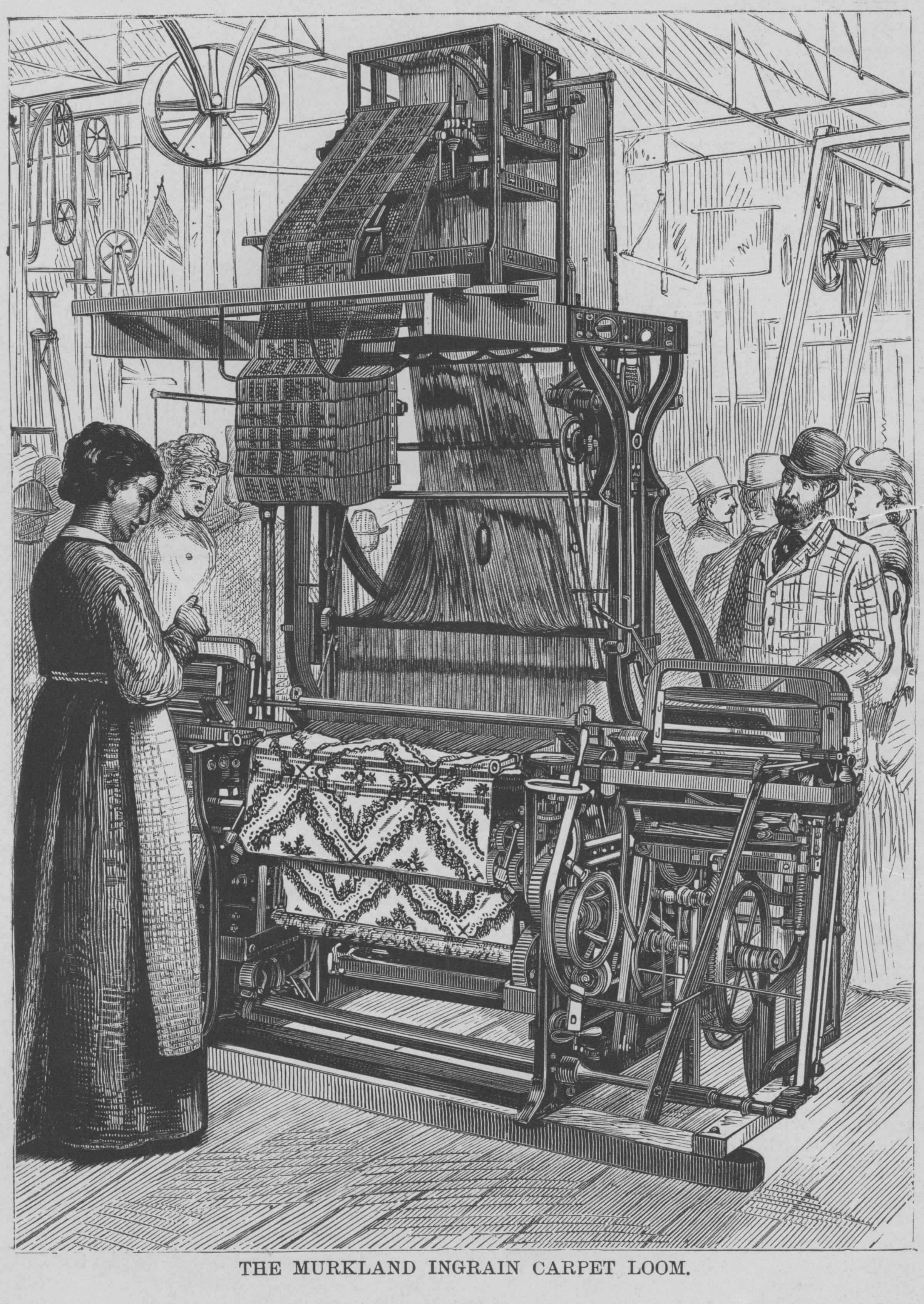

But then came the Industrial Revolution and its innovations, which included synthetic chemical dye and automated carpet weaving. Synthetic dye was invented in the late 18th century, and became more widespread over the 19th century. At the same time, carpet mills began functioning throughout the U.S. by the start of the 19th century, according to the Carpet and Rug Institute, the North American carpet industry’s trade association.

Suddenly, by the mid-1800s, you didn’t need to be part of an elite social class to afford red fabrics. “They become more and more accessible to common people,” Gutierrez says. The red carpet was already viewed as something only for the rich, but now, anyone could go buy one.

But, though the price of the red carpet decreased, its significance certainly didn’t lose any value. Evidence of that dynamic can be seen in one of the more widely known pre-Hollywood red carpet anecdotes, Gutierrez says, which is that the people of Georgetown, S.C., allegedly rolled one out for a visit from President James Monroe in 1821 — a 19th-century version of the path taken by the powerful Agamemnon to return home in Aeschylus’ play.

“Red-Carpet Treatment”

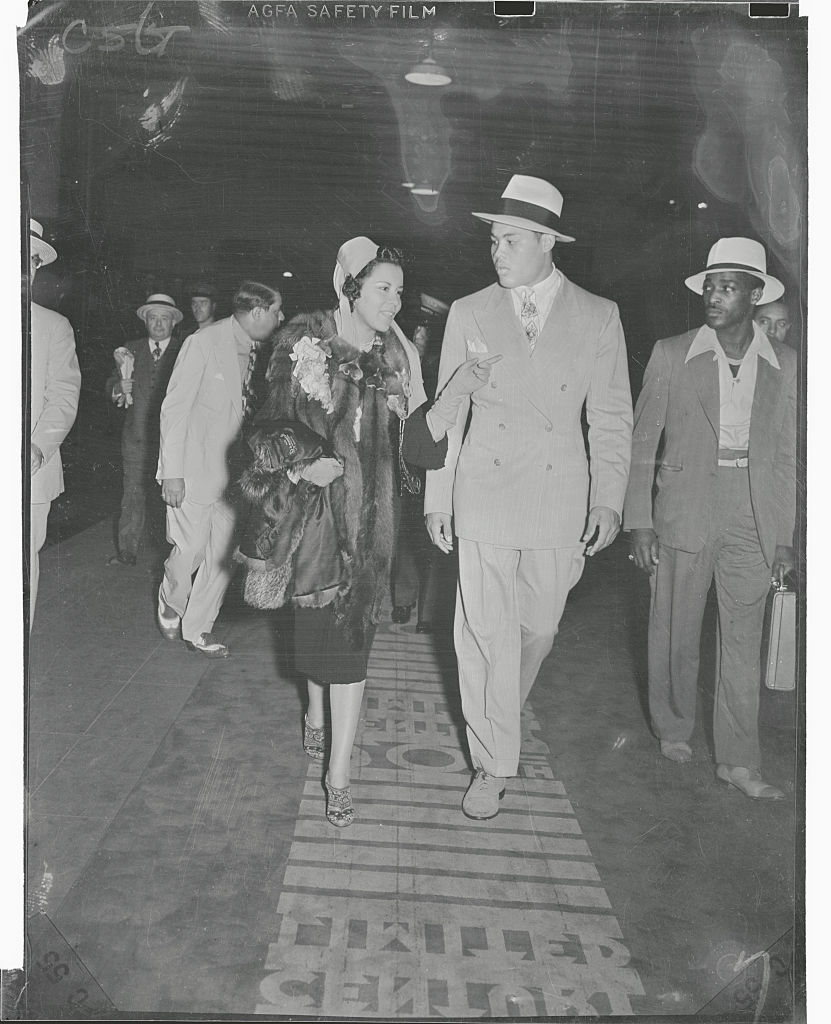

The phrase “red-carpet treatment” didn’t begin with Hollywood; rather, it began with a train station. The iconic 20th Century Limited Express on the New York Central Railroad, which ran from 1902 to 1967, could take people from New York to Chicago hours faster than any previous trains could. Gutierrez says that the advertising for the train upheld its speed as a measure of class and royalty — so naturally, a red carpet was rolled out in Grand Central Station for passengers making their way to that particular train.

This advertising added “red-carpet treatment” to the vernacular, and further established the narrative of the red carpet itself, according to Gutierrez. The carpet was designed in Art Deco style, and the allure didn’t end there. Once aboard the train, passengers enjoyed luxurious treatment.

“[The red carpet] keeps its sort of ‘special occasion’ cache, even as it becomes more and more democratic,” Gutierrez says. “You don’t actually have to be royal to walk on the red carpet to this train. You just have to be able to afford tickets.”

Hollywood Royalty

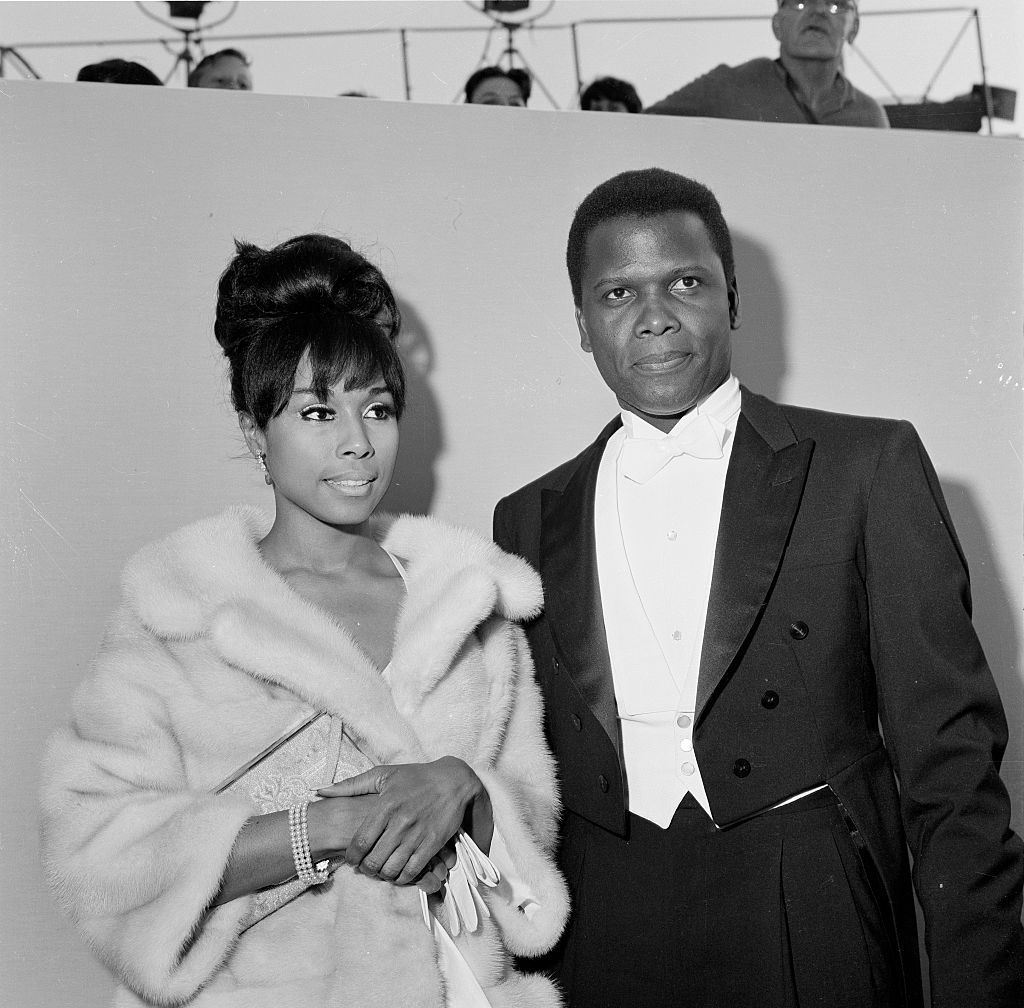

It was soon after the train’s use of the red carpet that its popularity traveled to California from New York. Legendary theater owner Sid Grauman is credited with bringing the custom to Hollywood for the 1922 premiere of Robin Hood at the Egyptian Theatre. Douglas Fairbanks, the star of the film and the “first king of Hollywood,” was one of the first stars to walk the red carpet as he arrived to the premiere.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences later adopted the tradition for their Academy Awards in 1961, when the pre-ceremony red carpet was first broadcast on television. But it wasn’t until 1964, when the carpet and ceremony were both broadcast in color, that the country could see the pop of red beneath stars’ feet. “It’s accessible to a mass audience after it’s broadcast on TV,” Gutierrez explains.

The red carpet as we know it — a path for the stars — has evolved over centuries. But those who now walk upon it serve a similar purpose in modern culture as they always did. “Movie stars,” Gutierrez says, “are sort of the modern-day royalty.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Rachel E. Greenspan at rachel.greenspan@time.com