Rep. Ilhan Omar faced calls from Republicans to resign from the House Foreign Affairs committee this week, following comments she made over U.S. politicians’ motivations for supporting Israel. After apologizing for evoking anti-Semitic stereotypes, the freshman Democrat indicated on Wednesday she has no intention of keeping a low profile on the committee.

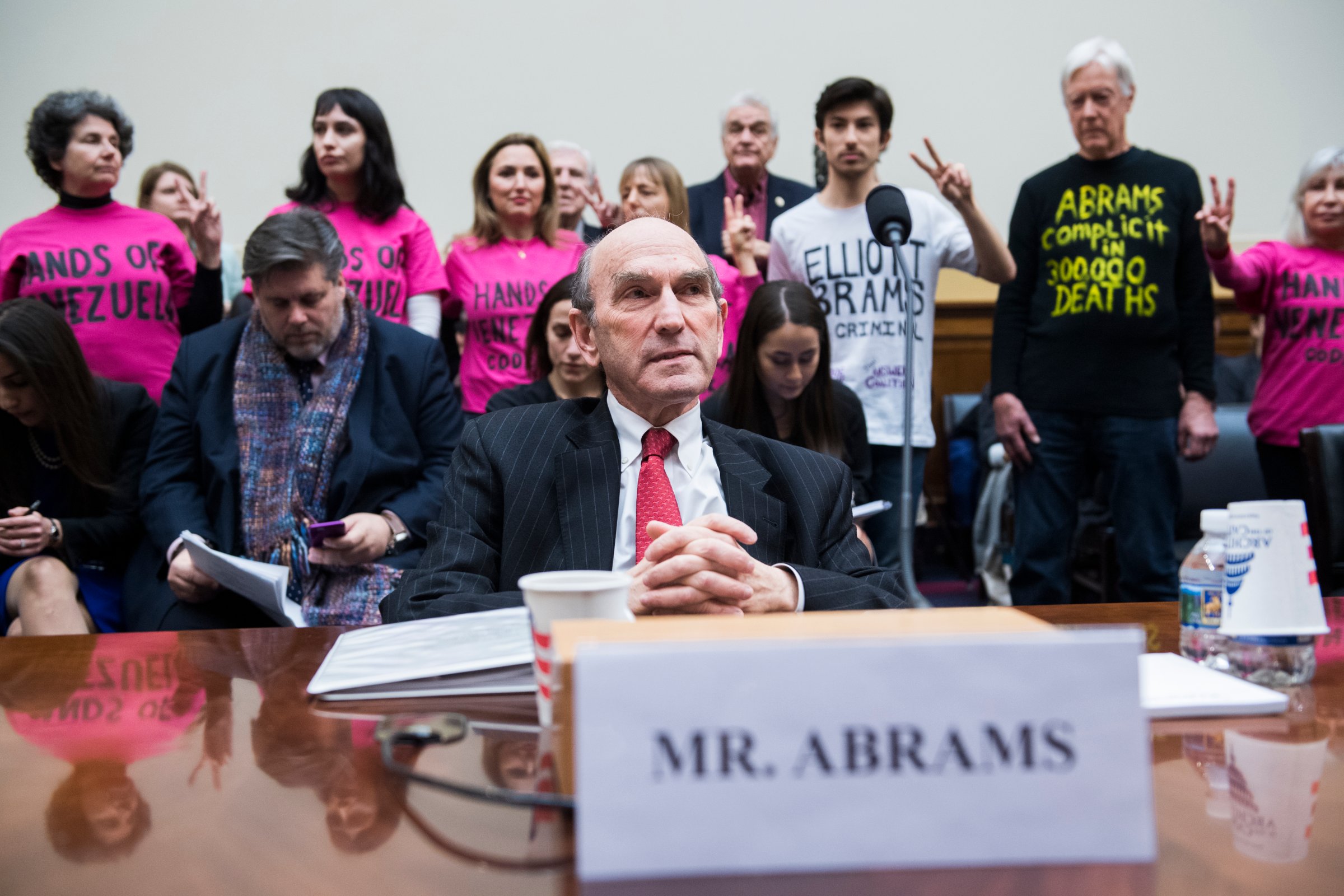

At a committee hearing on the crisis in Venezuela, where authoritarian president Nicolás Maduro has refused to step down amid a sprawling economic and humanitarian crisis, Omar entered into a heated exchange with Elliott Abrams. President Donald Trump appointed Abrams in January as special envoy for Venezuela. Omar spoke frankly about the diplomat’s controversial record in Latin America. Here’s the history behind her claims:

Who is Elliott Abrams and what happened when he testified at the Venezuela hearing?

Abrams, a longstanding neoconservative diplomat, served in the State Department during the Reagan Administration and played a key role in U.S. interventions in El Salvador, Nicaragua and Guatemala in the 1980s. He later joined the New York-based think tank, the Council on Foreign Relations, as a senior fellow. His appointment to oversee the U.S.’s response to the situation in Venezuela, where Trump has refused to rule out “a military option,” led many to raise concerns over his past dealings in the region, including his entanglement in the notorious Iran-Contra scandal. Omar confronted him with those concerns at the hearing.

“Mr. Abrams, in 1991 you pleaded guilty to two counts of withholding information from Congress regarding the Iran-Contra affair, for which you were later pardoned by President George H.W. Bush,” she said. “I fail to understand why members of this committee or the American people should find any testimony you give today to be truthful.”

Omar then brought up El Salvador’s 1981 El Mozote massacre, one of the darkest chapters in U.S. intervention in Latin America, accusing Abrams of having dismissed the massacre and pressing him to reconcile it with his previous characterization of U.S. policy in El Salvador as “a fabulous achievement.”

Abrams pushed back, refusing to answer what he deemed a “personal attack” and labeling Omar’s line of enquiry “a ridiculous question.”

Omar’s questioning riled many in the foreign policy establishment, who defended Abrams as a human rights advocate and devoted public servant. But others, particularly on the left, praised the congresswoman for a rare honest discussion of the more sinister effects of U.S. foreign policy.

What was the Iran-Contra scandal and how was Abrams involved?

Like most 20th century U.S. interventions in Latin America, the Iran-Contra affair began with Washington’s desire to prevent the spread of communism. In 1979, a left-wing movement, the Sandinista National Liberation Front, overthrew a right-wing dictatorship in Nicaragua, and began governing the country according to Marxist principles, including nationalizing private assets and unionizing workers. When Ronald Reagan entered the White House in 1981, he feared that Nicaragua’s government could encourage more leftist movements in Central America and potentially lead to a network of Communist states in Washington’s backyard.

The Reagan Administration — in which Abrams served first as Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs and then Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor — wanted to destabilize the Nicaraguan government. So the U.S. began funding right-wing rebel militias in the country, known as Contras. The Contras waged a decade of violent struggle against the government and committed widespread human rights abuses against civilians, according to human rights groups.

Congressional support for backing the rebels waned as media reports of the conflict in Nicaragua circulated, with liberal members of Congress calling it immoral and others fearing it could spark a dangerous confrontation with the Soviets. From 1982 to 1984, Congress passed a series of amendments limiting the CIA and the Department of Defense from helping the Contras to overthrow the Nicaraguan government. By 1984, all aid of any kind from the U.S. to the Contras was banned.

Reagan’s Administration, though, was undeterred. While the President reassured Congress and the public that he had stopped attempting to overthrow the Nicaraguan government, his Administration looked for covert ways to continue. The National Security Council sold arms to Iran to use in their war against Iraq — in contravention of a trade embargo on Iran — and then used $48 million of that money to fund the Contras. (Reagan maintained he himself did not know about the arms sales, a claim White House aide Oliver North denied—saying the President “knew of and approved a great deal of what went on with both the Iranian initiative and private efforts on behalf of the contras and he received regular, detailed briefings on both.”)

The Administration’s dealings became public in 1986, when Abrams was Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, and Congress began to investigate. Abrams pleaded guilty in 1991 to two misdemeanor charges for withholding information from two Congressional committees about the arms sales. The next year, President George H.W. Bush pardoned him.

What was the El Mozote massacre?

The next episode of U.S. history in Latin America that Omar brought up was the 1981 El Mozote massacre in El Salvador. She said Abrams had “dismissed ‘as communist propaganda [an episode in which] more than 800 civilians, including children as young as 2 years old, were brutally murdered by U.S.-trained troops.”

The El Mozote massacre was the worst massacre of civilians in modern Latin American history and came as the Reagan Administration attempted to bolster El Salvador’s right-wing government against leftist guerillas, called the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, or the FMLN.

Soon after he came to office in 1981, Reagan boosted military aid to the Salvadoran government and sent in U.S. forces to train Salvadoran troops to repress the rebellion. In December of that year, as those troops attempted to flush out the FMLN, they led a full scale aerial and ground assault on the eastern village of El Mozote, which they suspected of harboring guerillas. Over the course of four days, they murdered at least 900 residents of the village, including hundreds of children.

The following year, testifying before Congress as Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights, Abrams said the reports about El Mozote were “not credible.” Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, Reagan and Bush Administration officials defended Washington’s involvement in El Salvador, saying human rights were a priority in the campaign.

In March 1993, a U.N.-backed truth commission report concluded that, of 22,000 reports of human rights abuses (including extrajudicial killings, disappearances and torture) committed during the 12-year civil war, 85% were perpetrated by the U.S.-backed state forces. Responding to the report’s publication in 1993, Abrams said that “the Administration’s record in El Salvador is one of fabulous achievement,” and attacks on it were “a post-Cold War effort to rewrite history.”

Responding to Omar’s questions on Wednesday, Abrams cited the survival of democracy in El Salvador, which held its latest presidential elections in early February, as proof of Washington’s successful intervention, reiterating his claim that it’s “a fabulous achievement.”

How does the U.S.’ past involvement in Latin America relate to the current situation in Venezuela?

The Trump Administration, along with most Western democracies, has refused to recognize Maduro’s second term in office and on Jan. 23 officially recognized Juan Guaidó, an opposition leader who heads up Venezuela’s parliament, as interim president. Since then, speculation has mounted around a possible U.S. military intervention in the country to help Guaidó take power (Venezuela’s military continues to back Maduro as president.) Both Trump and Guaidó have refused to rule out that option.

There are key differences between the crisis in Venezuela today and the ideological battles in El Salvador, Nicaragua and elsewhere in the region in the 1980s. But Washington’s interest in ousting Venezuela’s socialist government has revived historical tensions. Maduro has blamed the U.S. for his country’s troubles on U.S. sanctions and warns his supporters about the historical threat of “Yankee imperialism.”

Some argue that the appointment of Abrams — who, according to reporting by The Guardian gave his tacit approval of a coup attempt against Maduro’s predecessor while working in George W. Bush’s administration in 2002 – to a key advisory role, has strained an already tense foreign policy situation. Others, such as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, think his expertise in the region makes him “a true asset” in the U.S.’ response to Venezuela. In any case, Wednesday’s confrontation between Omar and Abrams shows that Washington’s past in Latin America weighs heavily on the present.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Ciara Nugent at ciara.nugent@time.com