When the Myanmar military unleashed its campaign of rapes, arson and murder against the Rohingya Muslims in 2016, members of the persecuted minority’s diaspora were swift to act. They documented the violence. They petitioned the international community. And they helped spotlight the unfolding humanitarian catastrophe as more than 700,000 refugees fled to neighboring Bangladesh. Yet in the fight to hold Myanmar accountable, the Rohingya diaspora is too often overlooked.

Historically, the pursuit of justice for human rights violations has been strengthened by the diaspora’s participation. From Rwanda, to Cambodia, to Armenia, mobilizing the diaspora can be a powerful way to engage the community and translate local context. Despite this, our team at Fortify Rights has routinely encountered diplomats, donors and others who dismiss the Rohingya diaspora as disconnected and irrelevant.

In reality, as dispersed populations that maintain a sense of collective identity, diasporas provide a vital link between their host countries and their homelands. The Rohingya are no different.

Today, more Rohingya reside outside Myanmar than inside the country. The diaspora initially comprised Rohingya uprooted by decades of violence and institutionalized discrimination — including sporadic military campaigns and a denial of citizenship. This longstanding exodus has established outposts around the globe, including refugee camps in Bangladesh, as well as communities resettled in America, Europe and Australia.

A second, newer group consists of the Rohingya who fled Myanmar’s most recent waves of violence in 2016 and 2017 in the fastest refugee outflow since the Rwandan genocide.

The Rohingya, Burma's Forgotten Muslims by James Nachtwey

Now more than ever, the international community needs to work with both arms of the Rohingya diaspora to push for accountability and justice.

No one knows this better than the Rohingya themselves — they are the witnesses, the survivors, the people who remain with these issues long after international attention fades.

Myanmar has a long history of diasporas leading change, especially during the nearly 50 years of direct military rule that lasted until 2011. Exiled women’s organizations, such as the Burmese Women’s Union and the Women’s League of Burma, documented human rights violations when the nation was still closed off to the outside world. They lobbied international governments and pressured Myanmar to end impunity for military attacks against civilians.

Similarly, Rohingya advocates are working to ensure an end to the ongoing genocide of their people.

Read more: Myanmar’s Attempt to Destroy the Rohingya Muslims

For example, Rohingya-led news sites like the Kaladan Press Network, established in Bangladesh, and Rohingya Blogger, established in Germany, regularly report on violations perpetrated against the community in Myanmar and Bangladesh.

Members of the Rohingya diaspora have pressured the U.N. and international governments to respond to the spiraling humanitarian crisis. Consider Razia Sultana, a Rohingya human rights lawyer who grew up in Bangladesh and founded the Rohingya Women Welfare Society. After working with Fortify Rights and with her own team to document the accounts of Rohingya women and girls who suffered sexual violence, she testified before the U.N. Security Council in April 2018.

In December, Dr. Ambia Perveen, the vice chair of the European Rohingya Council, informed the International Criminal Court of atrocities committed in Myanmar and the post-traumatic stress many Rohingya survivors face. Tun Khin, the President of the Burmese Rohingya Organization U.K., has spent more than a decade testifying before Congress, the U.K. Parliament and elsewhere. And from Europe, Nay San Lwin regularly provides updates on the Rohingya’s violence-wracked homeland.

Members of the diaspora are also the champions and defenders of their community. Take for instance Sharifah Shakirah, founder of the Malaysia-based Rohingya Women Development Network, which lobbies for better protections for Rohingya refugees.

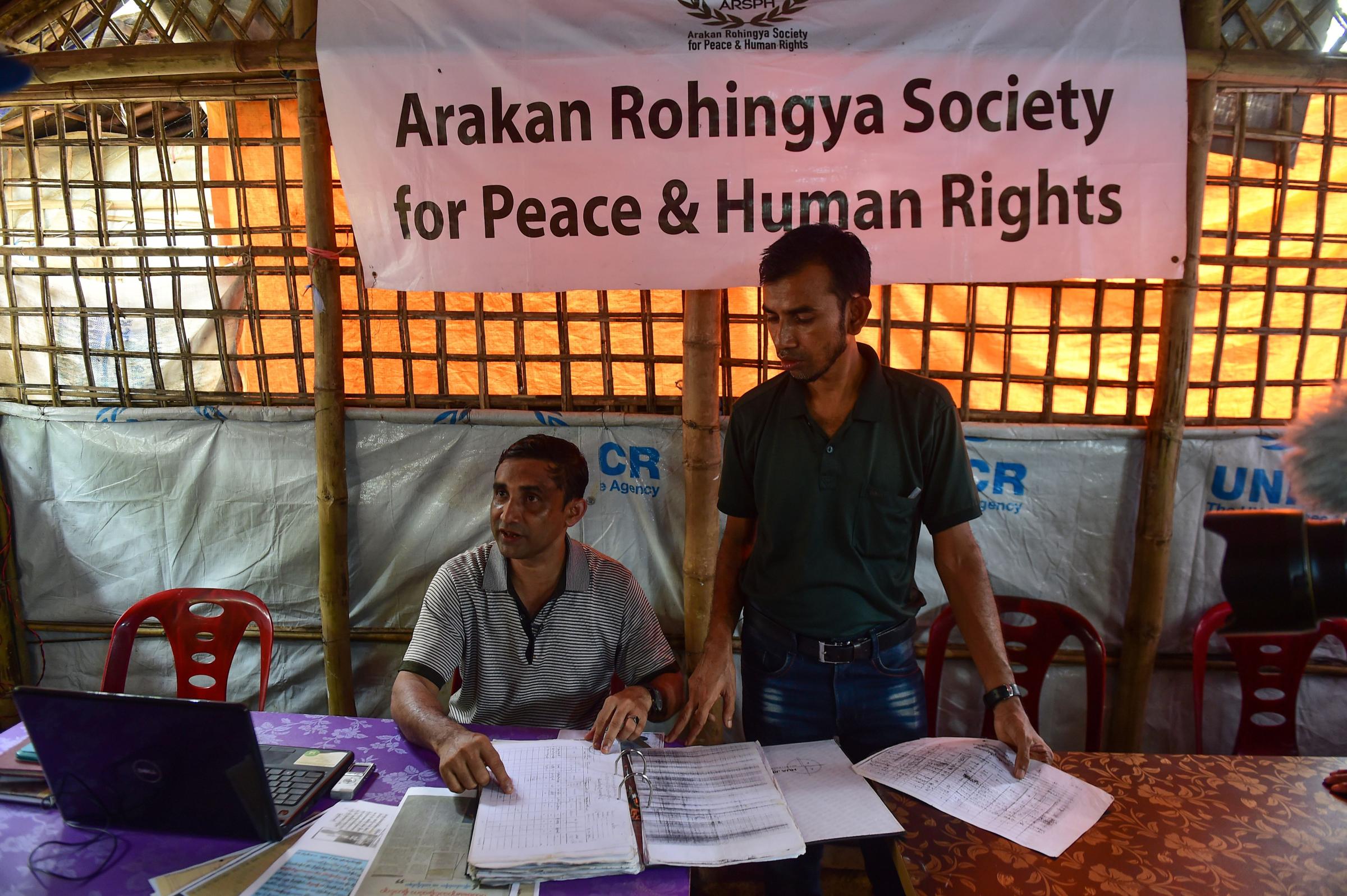

The new Rohingya diaspora also has its own movements, groups like the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights, which advocates, among other things, for more Rohingya involvement in running the camps in Bangladesh.

Rohingya groups around the world have also been crucial in the push to accurately label the situation in Myanmar a genocide. In December 2018, 23 Rohingya-led organizations issued a joint statement calling on the U.S. government to make a genocide determination and compel tougher punitive action against Myanmar, which denies atrocities. Later that same month, the House of Representatives passed a resolution declaring the ongoing persecution a “genocide,” even as the Trump administration continues to avoid the term.

On this issue and others, the Rohingya diaspora is already acting as a transnational link between their homeland and their host countries. They have local knowledge, as well as an understanding of the history and context in Myanmar that can uniquely assist in finding solutions for accountability and restoring citizenship to the mostly stateless group.

The international community would benefit by making the Rohingya diaspora a part of these processes. For starters, non-governmental organizations should involve Rohingya in program designs and implementation, and policymakers should provide them with seats at the table.

Some argue that diasporas can fuel conflict and extremism. However, in our team’s experience, the Rohingya diaspora overwhelmingly supports nonviolent action.

The fact is, the Rohingya diaspora is integral to international justice and accountability.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com