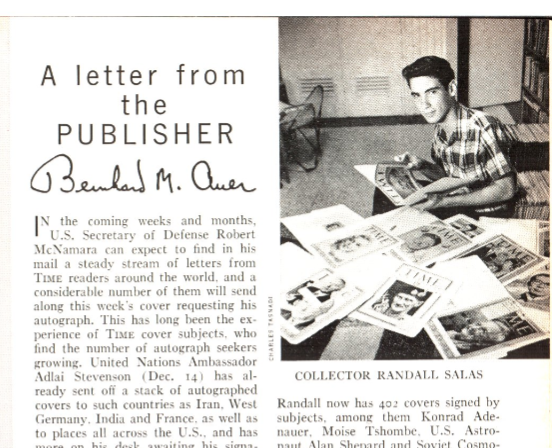

In a note in the Feb. 15, 1963, issue, then-TIME publisher Bernhard M. Auer introduced readers to a few particularly dedicated subscribers who had made a habit of sending away their copies of TIME to their respective cover subjects for their autographs. One of those collectors was a 17-year-old from Caracas named Randall Salas.

“Randall, who was born in Curaçao and speaks English, Spanish, Dutch and Papiamento (a Caribbean lingua franca), started his collection only in 1959. But he had a head start: his father, an insurance broker, has been reading TIME since 1935, and had saved many back copies,” Auer explained. “Randall now has 402 covers signed by subjects, among them Konrad Adenauer, Moise Tshombe, U.S. Astronaut Alan Shepard and Soviet Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, Marilyn Monroe (who signed in red ink), J. Paul Getty (who signed in black), and Tibet’s Dalai Lama. Some of the signers send more than their autograph: John F. Kennedy enclosed an autographed picture with one of the two covers he signed; Abdul Karim Kassem (whose signature is a collector’s item now), sent a copy of a speech he had just made; J. Edgar Hoover added some FBI pamphlets, and Soviet Defense Minister Malinovsky scribbled some propaganda right on his face: ‘We struggle for peace all over the world.'”

Not everyone said yes, the note acknowledged. Winston Churchill didn’t have time for autographs, a prison warden said that convicted criminal Caryl Chessman was not permitted to give them, and U.S. Navy Admiral Hyman Rickover apparently had a personal rule that he didn’t sign anything for people he didn’t know. Salas tried to get around that by sending Rickover a photo of himself, but that didn’t work either.

Despite the occasional setback, Salas kept collecting.

Now, 56 years after that little profile of the collector appeared in the magazine, the 73-year-old retiree’s collection includes about 1,500 autographed issues of TIME — but he has stopped adding to the group, and now intends to look for a way to sell or donate what he has.

And the reason for stopping, he told TIME by phone and during a recent sit-down in Caracas, is a window into how the world has changed in the last half-century.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In the early days of the collection, Salas says, the research was hard but the returns were high. It all started when an uncle visited Cuba and got Fidel Castro’s autograph on an issue of TIME. The uncle gave the magazine as a gift to then-13-year-old Randy, whose father encouraged him to keep it going. Though the choice of TIME was mostly a coincidence — his father happened to have kept years’ worth of back issues, and it was easy to come by in Caracas — the collection soon became a passion. And though some addresses were easy to find, such as those for Senators and astronauts, others took serious research, even more of a feat in the pre-Internet era. Still, he estimates that in the first decades of his collecting, about 80% of the magazines he sent out were successfully returned. (That’s including special situations such as that of Libyan strongman Muammar Gaddafi, who sent an autographed photograph but apparently didn’t want to endorse TIME’s depiction of him by actually signing the magazine.) Salas’ appearance in the magazine helped too, as readers around the world began to send him older issues they held onto.

The autographs were an invitation to learn more about the people influencing world events. A magazine signed by Mother Teresa felt like touching hands with a saint.

“Every time that I received a poster it felt that I had direct contact with someone who signed it,” he says.

More recently, however, he estimates that only about 10% of the magazines he sent out would come back with an autograph. It had become harder to find TIME on newsstands in Caracas — a city that was, the week of this interview, in an active state of crisis — and the mail was less reliable. Addresses were harder to find, and TIME covers more frequently illustrated news topics rather than featuring portraits of individuals. Perhaps most importantly, he guesses that celebrities had become jaded by their knowledge of the autograph resale market, and didn’t want to send something to someone who would turn around and sell it. And Salas’ two daughters, neither of whom live in Venezuela, have encouraged him to use his retirement as a time to travel instead of waiting for the world to come to him.

That little bit of connection between the person changing the world and the person living in it has faded. Despite celebrity collectors like Judd Apatow keeping the hobby in the spotlight, the golden age of the autograph has perhaps ended. But, at least for Salas, its impact lingers.

“The collection is part of my life. I feel proud, satisfied, I feel that it has educated me and I have learned so much,” he says. “I practically know the story of the 1,500 people here. I can assure you that if I ask any of you here who these people are, you could not tell me every single one. Having the cover autographed makes me feel like a part of that person, that’s what’s most important to me.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com