You don’t have to be a botany expert to decipher what it means when somebody sends you a rose. Every year on Feb. 14, millions of people exchange the flower to express their love — and upwards of 250 million are produced annually for Valentine’s Day, as of 2018, according to the Society of American Florists.

But the rose’s life as a symbol didn’t begin with romance.

In Victorian England, women’s roles in society were limited by custom and norms. Within those strictures, learning the language of flowers — the notion that each and every flower has its own meaning — was one activity deemed domestically appropriate for them. And for ladies in that situation, its communicative possibilities also held an appeal that other domestic arts lacked; “the possibility that some women sought methods of covert communication and expression exists,” Mary Brooks wrote in “Silent Needles, Speaking Flowers.”

The early popularization of this practice is credited to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of a British ambassador to Turkey in the 18th century. Enthralled by a Turkish version of flower language, Lady Montagu wrote a series of letters home to England in 1716. She described the Turkish tradition as a way of assigning meaning to objects in order to send secret love letters. Montagu’s letters, published in 1763, wrote of her perceptions of this practice: “There is no colour, no flower, no weed, no fruit, herb, pebble, or feather that has not a verse belonging to it: and you may quarrel, reproach, or send letters of passion, friendship, or civility, or even of news, without ever inking your fingers,” she wrote.

But the Lady was actually incorrect in her interpretation.

As Beverly Seaton explains in The Language of Flowers: a History, the Turkish flower language sélam (which means “hello” in Arabic) did not function the way Montagu understood. In sélam, “the significance of the objects is not symbolic, but relates to words that rhyme with the object’s name,” Seaton explained. There was no sentimentality surrounding the flowers themselves.

In spite of Montagu’s misunderstanding, word of the concept spread. Langage des fleurs, a dictionary for the language of flowers by Charlotte de Latour, was published in France in 1819, a century after Montagu’s discovery. Nine editions of the English translation of the book, which alphabetically defined each flower, were printed within three decades of its publication, according to The Culture of Flowers by Jack Goody. De Latour’s translated Language of Flowers covered most popular flowers we buy, sell and give today, from the mistletoe’s importance during Christmas to the musk rose’s symbolization of “capricious beauty.”

In de Latour’s chapter on the rose, the flower is not only defined as meaning “love,” but the plant itself is romanticized. “Who that ever could sing has not sung the Rose! The poets have not exaggerated its beauty, or completed its panegyric,” she wrote. Not that that stopped de Latour from attempting to add to the panegyric of the rose herself: “Nature seems to have exhausted all her skill in the freshness, the beauty of form, the fragrance, the delicate colour, and the gracefulness which she has bestowed upon the Rose,” she wrote.

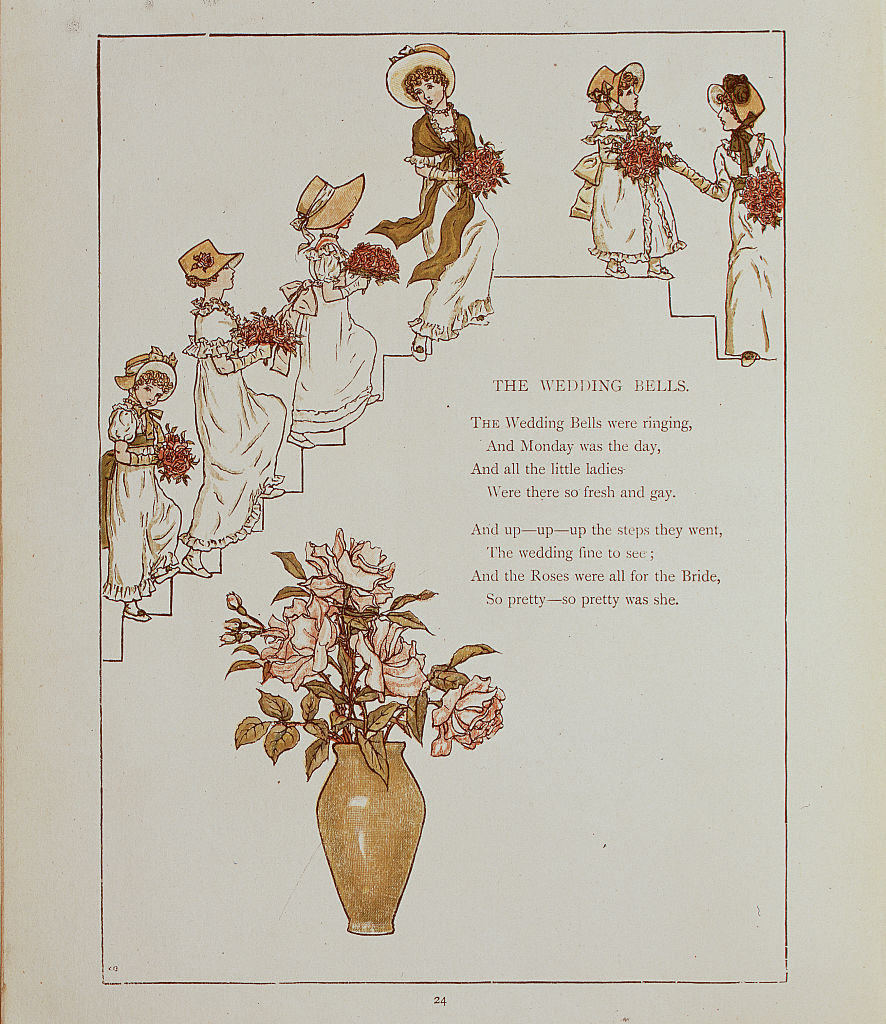

Throughout the 19th century, books about the language of flowers circulated throughout England. Prolific illustrator Kate Greenaway’s book, published in 1884, accompanies Latour’s definitions with drawings for children.

The trend took on a life of its own, spurring stories and poetry that pointed to the flower’s lasting emotional power.

Charlotte Elizabeth’s Floral biography: or, Chapters on flowers (1848) was a meditation on the way the author’s life could be categorized, in a way, by experiences with flowers. Elizabeth wrote of the way a rose brought her happiness during one New Year’s celebration: “I know that, when our glasses were replenished, with orange wine, to drink a happy new-year all round, the Christmas rose which I held in my hand formed a portion of my new-year’s happiness, by no means inconsiderable.”

Meanwhile, sales of roses skyrocketed. Botanists throughout Victorian England and France worked to develop new kinds of roses in the 19th century, says Stephen Scanniello, curator of the Peggy Rockefeller Rose Garden at the New York Botanical Garden. In the northeastern U.S., the American Beauty rose was spreading. This cultivar was reportedly shipped from New Jersey to Queen Victoria herself, Scanniello tells TIME. The American Beauty, dubbed the “millionaire’s rose” for its expensive price point in the 1800s, is the variety of the flower we often purchase and send for Valentine’s Day today.

Though it had been the Victorians who ingrained the rose’s meaning into modern society, they weren’t the first in history to assign symbolic meaning to objects found in nature. The language of flowers is merely one aspect of this larger phenomenon, says Amy King, an associate professor of English at St. John’s University. “It’s part of a yearning, I believe, to give language to the phenomenal world,” King told TIME in an email. Today, this desire has not gone to the wayside. Though most of us are not fluent in the language of flowers, we still blush when we’re sent a bouquet of roses.

To match a feeling of desire, the striking aesthetic beauty of the flower makes it an obvious choice, King posits: “Parts of nature that can so readily arrest our mental attention, one might argue, are particularly suited to the expression of romance.”

Beyond this fascination, the color of the traditional rose may play an important role in its enduring relationship with love, argues Arielle Eckstut, the author of The Secret Language of Color. A blush brings redness to the face in moments of attraction and desire. Connected to both sexuality and status, the power of the red is not exclusive to romance — it’s also the color of the Chinese New Year and green’s companion on Christmas. It’s the “most fundamental of colors,” Eckstut tells TIME. Along with its red color, the rose’s shape and fragrance contribute to its beauty, Scanniello says.

Throughout the long history of floral definitions — and despite Lady Montagu’s misinterpretation — one thing is certain. People from the archaic period to today have viewed flowers through a romantic lens. Even Greeks and Romans between the 4th and 5th Century BC, Scanniello explains, adorned themselves in rose garlands during wedding ceremonies.

But can we blame them?

“The beauty of the flower,” Scanniello says, “definitely has created all the attention that the rose gets.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Rachel E. Greenspan at rachel.greenspan@time.com