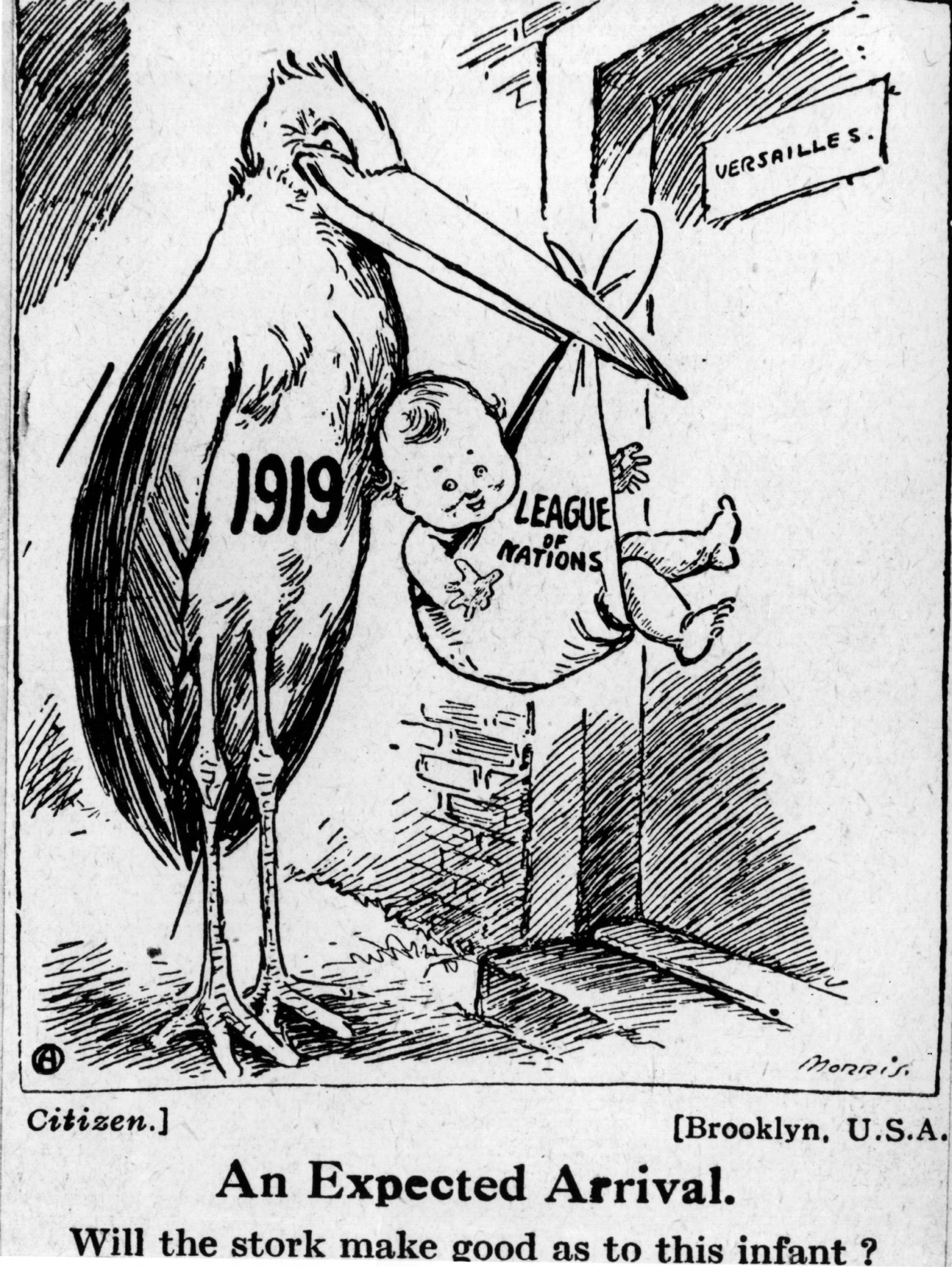

A century ago Friday, on Jan. 25, 1919, nearly 30 countries approved a proposal to create a commission to establish the League of Nations. Meant to keep the peace in the aftermath of World War I, the League—championed by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson—was approved at the Paris Peace Conference and went into effect a year later. Though it only functioned until April 1946, it is considered a forerunner to the United Nations and its impact can still be seen today.

TIME spoke to Stewart M. Patrick, senior fellow in global governance and director of the International Institutions and Global Governance (IIGG) Program at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), for answers to some basic questions about the League’s legacy:

TIME: What did the League of Nations do right?

PATRICK: There had been many plans throughout history, since the days of Immanuel Kant, to come up with a permanent institution to help create perpetual peace or reduce the prospects of war. The League of Nations is significant because, even though it failed, it was the first time a bunch of sovereign nations got together and said, ‘We’re sovereign nations, but we’re going to try to combine our power to try to keep the peace.’ It also had some modest successes particularly dealing with certain territorial disputes. The League was not in vain if you consider that there were lessons learned from its failings.

Why did the League of Nations fail?

There had to be unanimity for decisions that were taken. Unanimity made it really hard for the League to do anything. The League suffered big time from the absence of major powers — Germany, Japan, Italy ultimately left — and the lack of U.S. participation.

Henry Cabot Lodge, the chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, was worried involvement in the League would hamstring the U.S. from determining its own fate and demanded all these reservations to U.S. membership. The biggest issue was Article X, which said League members are committed to protecting the independence and territorial integrity of other countries around the world, and Lodge interpreted that as an automatic decision that if a country was invaded or faced aggression, the U.S. would have to come to [its] aid. The reality was it was more moral than an iron-clad legal commitment. And as a result the Senate rejected U.S. membership in the League of Nations.

What kind of role did the League of Nations play in World War II?

Maybe the U.S. could have helped prevent the Second World War if it hadn’t, in a sense, abdicated its role in the world. During and immediately after the Second World War, there was a recognition that we really blew it and we need to be a part of the United Nations. The U.N. Security Council did have more teeth, its decisions were legally binding and didn’t have to be unanimous.

The League showed the inherent limitations of collective security, which is basically an “all for one and one for all” ethos; countries have to treat the outbreak of war anywhere as worrisome and a threat and we have to respond to it. The reality is [that doctrine] doesn’t take into account countries’ other interests or the context. For instance, when Italy invaded Ethiopia in the mid-1930s, Britain and France who needed Italy as it was cozying up to Nazi Germany, chose to appease. Same thing when Hitler started gobbling up little bits of nearby countries.

What was going on in the rest of the world while the League of Nations was functioning?

It was a period of hyper-nationalism at the end of the First World War. It was a period of extraordinary economic turbulence and turmoil when there was mistrust over whether the global economy could bring prosperity to people. There was quite a lot of populism and authoritarian strongmen coming to the fore, which helped give rise to, on the far right, Nazism and Fascism, and on the left, Marxist-Leninism. The U.S. had entered the First World War decisively to restore the global balance of power, but then it decided, Nah. In a sense, it stood idly by during the 1920s. That was okay when the economy ended up doing pretty well for a while, but then the Great Depression happens and countries start being more territorially aggressive and the old European balance and Asian balance starts to go south.

Do you see any parallels between that world and today’s world?

In many ways, debates going on now are a total throwback to debates over the U.S. role in the world [following World War I]. In some ways, Trump, in my view, has a pre-1941 mindset. He would be quite comfortable going back to that era in which the U.S. didn’t have to exercise these global responsibilities. Contexts are always different, though there’s that saying, history never repeats itself but it often rhymes.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com