The vast majority of cancers do not have one obvious cause, making them complex both to understand and treat. Cervical cancer is one of the few exceptions: “Virtually all” cases are caused by human papillomaviruses (HPV), according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Armed with this knowledge, experts have for decades stressed the importance of regular cervical cancer screenings, which can catch HPV infections and related abnormalities before they develop into deadly disease. And yet many women still don’t get tested as much as they should.

The screening rate isn’t entirely clear. A study published last year found that, as of 2014, screening adherence ranged from a low of about 60% for women ages 50 to 65 to a high of 77% for women in their 30s. Meanwhile, a January Mayo Clinic report found that in one Minnesota county representative of many in the Midwest, cervical cancer screening rates were “unacceptably low,” hovering around 54% of women ages 21 to 29 and 65% of women ages 30 to 65.

“Most of the cervical cancer cases in our country are either women that have never been screened previously, or that haven’t been screened regularly or that haven’t had follow-up [care] for abnormal results,” says Dr. Kathy MacLaughlin, a family-medicine physician at the Mayo Clinic who co-authored the new report.

But why aren’t women getting screenings that could save their lives?

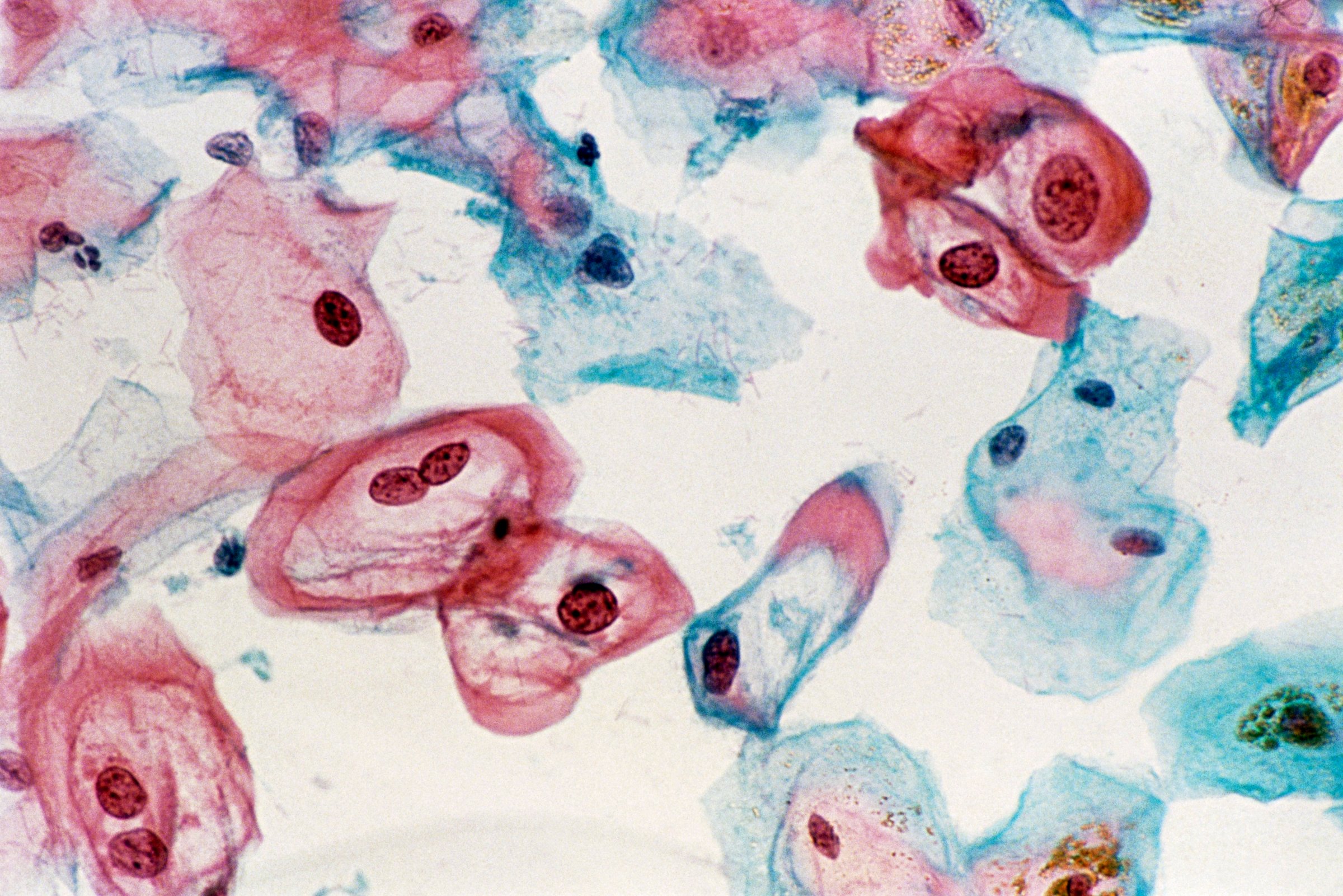

Shifting guidelines are part of the problem, MacLaughlin says. For decades, women were advised to get a yearly Pap smear, a test that involves sampling cervical cells and examining them under a microscope. Then, in 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), one of the country’s leading preventative medicine authorities, began officially recommending waiting three years between tests. And in 2018, the USPSTF changed its recommendations again to say that most women ages 30 to 65 can get an HPV test — which looks for common viral strains directly — every five years, if they prefer that to a Pap smear every three; they can also get a combination of the two tests every five years. (Women ages 21 to 29 should still get a Pap smear every three years rather than an HPV test, according to the USPSTF.)

MacLaughlin says the science behind these guidelines is sound, but she fears they’re causing more women to put off appointments, simply because of human nature. “If you are told you should do something every year to take care of yourself, it often turns into every two years,” she says. “And if we’re saying every three to five, that turns into four, five, six, seven years.”

But an even larger issue, MacLaughlin says, is the barriers to access that prevent screening in the first place. Socioeconomic and geographic issues, like poverty or being unable to travel to or find time for appointments, can make it difficult for women to get in for testing — and those problems only compound if a screening uncovers abnormal results that needs follow-up care, which can be costly and inconvenient to schedule. Those obstacles partially explain why cervical cancer death rates are twice as high in low-income U.S. counties compared to affluent ones, according to a January American Cancer Society study.

“If you’re coming from a lower-resource setting, that can get in the way of coming in and getting that screening performed,” MacLaughlin says. “If women were in a setting where they could have regular screening, or if it were available to them and affordable in their own setting, I don’t think we would see those disparities.”

Past research has shown that strategies like one-on-one education, reminders and incentives from providers and media campaigns can help improve screening rates. Technology, however, has not traditionally been at the center of this effort.

A new, artificial intelligence-powered algorithm developed by NCI researchers could change that.

The algorithm works by analyzing cell-phone-quality images of a woman’s cervix and determining if it looks normal, precancerous or cancerous. Dr. Mark Schiffman, a member of NCI’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics and senior author of a new study about the innovation, says the tool is potentially powerful enough to halve global cervical cancer mortality among women ages 25 to 49, potentially within the next couple decades.

“To see something that dead-on works is just thrilling,” Schiffman says. “These new algorithms are scarily fantastic.”

Schiffman and his colleagues trained the algorithm using thousands of cervical images they’d collected over seven years of clinical research. They told the system whether each case had turned out to be normal, precancerous or cancerous. Once trained and presented with an array of cervical images, the algorithm was “capturing virtually all cases that turned into precancer or cancer — not just for that same day, but within the next seven years,” Schiffman says. It was so accurate, he says, that he “first looked at it and said, ‘This can’t be right.'”

The tool isn’t ready for deployment yet, but Schiffman says it likely will be within two to three years. And when it is, he says it could revolutionize cervical cancer screening, particularly in areas of the world that are still relying on low-tech and somewhat inaccurate methods like visual inspection with acetic acid, through which health workers apply acetic acid to the cervix and look for visual changes that could indicate disease.

The AI algorithm promises a precise and affordable solution that could be used not only by doctors, but also local health workers or personnel at traveling health fairs, Schiffman says. The tool is also fast-acting: If the algorithm finds abnormalities, a woman could near-instantaneously get treatment — which, for many early-stage cases, usually just entails freezing affected cells with a probe, just as one would a wart. In theory, screening and treatment could happen during the same visit, Schiffman says.

“We don’t need a doctor. We don’t need anybody but someone who can find the cervix,” Schiffman says. “Everything’s done right there, it’s instantaneous in terms of telling you what it is and the treatment is 45 seconds.”

Schiffman says the algorithm’s potential is largest for countries in the developing world, where cervical cancer is sometimes the leading cause of female cancer death. But Dr. Micael Lopez-Acevedo, a gynecologic oncologist at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences who was not involved in the study, says it also holds promise for the U.S., because it could reduce the number of necessary appointments.

That’s because Pap smears are not considered diagnostic tests in the U.S., Lopez-Acevedo explains. If one shows an abnormal result, a patient must come back in for more advanced testing and, if necessary, treatment. If an AI algorithm like Schiffman’s were accurate enough, it could feasibly streamline that multi-step process, Lopez-Acevedo says.

Lopez-Acevedo adds that existing technology could also raise screening rates, at least while AI solutions like Schiffman’s are fine-tuned. Communicating with patients via text messages or even social media, rather than letters or phone calls, could improve engagement rates and get more people to come in for care, he says. And MacLaughlin says making simple concessions to patients, like adding night and weekend hours to clinics, could make a huge difference.

And all of the experts agree that another opportunity lies in stopping HPV at its source by increasing vaccination rates. The CDC recommends that all children get vaccinated against HPV at age 11 or 12, but adherence rates continue to come in below targets. They are rising, though: As of 2017, according to the CDC, about 65% of teenagers had gotten at least one of two required doses, which are administered at least six months apart. (The vaccine was recently approved for adults as well.)

In an ideal world, Schiffman says, the use of tools like his would be combined with an effective one-dose vaccine, especially in developing areas where cervical cancer is common and deadly. Making that goal a reality, he says, should be a priority for the science community.

“This is a cancer that’s both terrible and preventable. This is the only cancer that we know that we can prevent,” Schiffman says. “We’re trying to get people now to do something that’s of undeniable good to everybody.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com