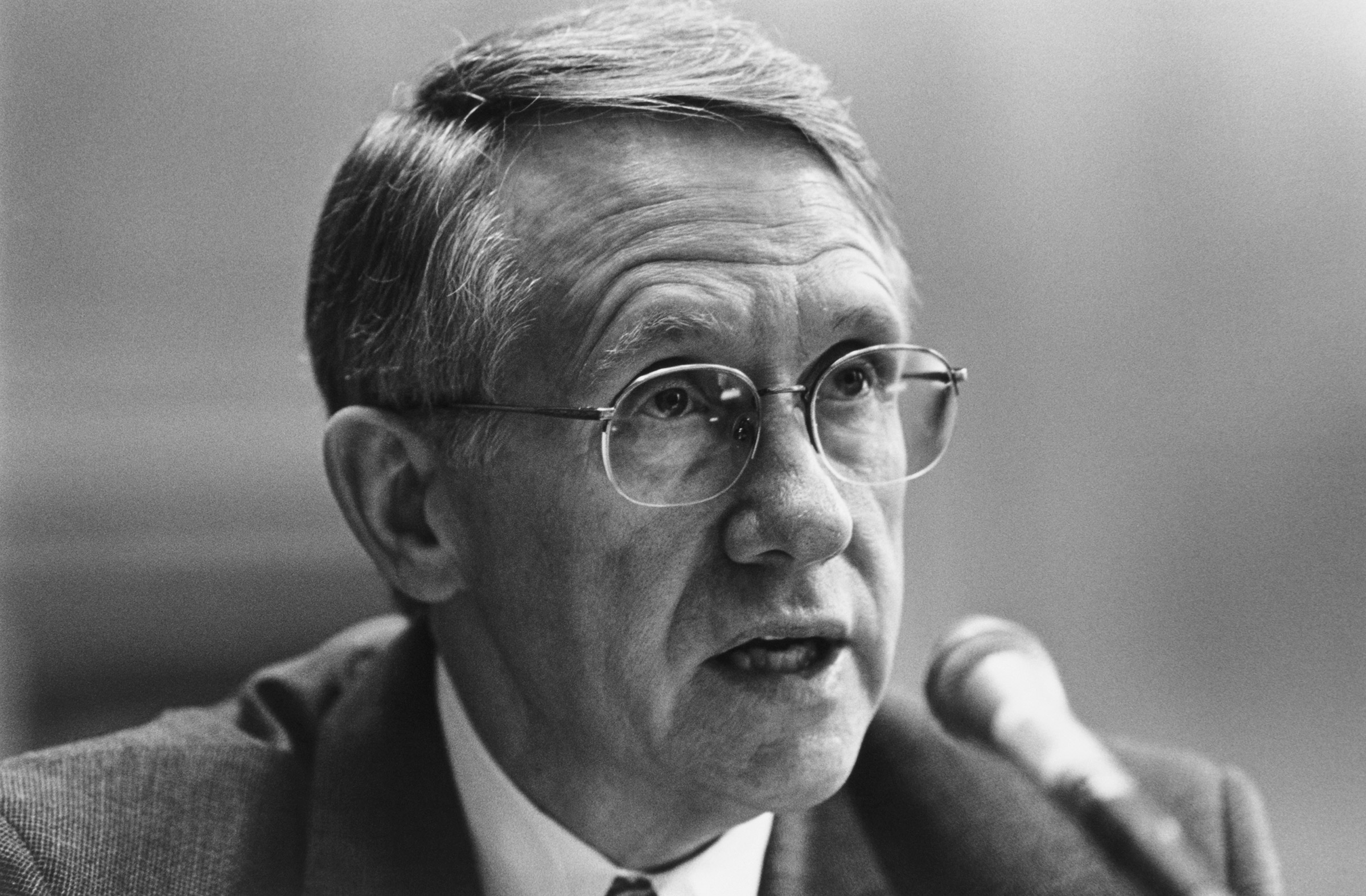

Harry Reid rose from hardscrabble roots to the heights of American politics, his canny temperament and underdog’s grit taking him from a one-room shack in Searchlight, Nev., to the office of U.S. Senate Majority Leader. The former Democratic senator from Nevada reshaped the U.S. Senate and transformed his home state’s political culture, earning a reputation as a master dealmaker despite his laconic demeanor. He steered his party through the tumult of the Bush and Obama eras, turning against the Iraq War, cheerleading President Barack Obama’s historic rise and shepherding the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

Reid died Tuesday at 82 at his home in Henderson, Nev. The cause was not immediately disclosed. He had previously battled pancreatic cancer, but said last summer that it was in remission.

“He was tough-as-nails strong, but caring and compassionate, and always went out of his way quietly to help people who needed help,” the current Senate Majority Leader, Chuck Schumer, said in a statement Tuesday. “He was a boxer who came from humble origins, but he never forgot where he came from and used those boxing instincts to fearlessly fight those who were hurting the poor and the middle class.”

Harry Mason Reid was born in 1939 in a gold-rush ghost town separated from Las Vegas by 50 miles of empty desert. The family lived in a shack made of stuccoed-in railroad ties with no running water; Reid learned to swim at one of the brothels that were the town’s main amenity. His father, a miner, was a brooding, silent drunk who would later end his own life with a shotgun to the head. Reid, nicknamed “Pinky,” hitchhiked 45 miles each way to the nearest high school, in the Las Vegas suburb of Henderson.

It was the fight in Reid that provided an escape from his tough circumstances. In high school, he met the man who would become his mentor, Mike O’Callaghan, a one-legged Korean War veteran who taught Reid to box and would go on to serve two terms as governor. It was also in high school that Reid met and wooed Landra Gould, a Jewish girl whose parents were so suspicious of his motives that he once punched her father in the face to take her out on a date. The couple eloped to Utah, where Reid had, with O’Callaghan’s help, gotten a scholarship to a junior college.

There had been no religion in Reid’s upbringing — the closest thing to faith, he wrote in his 2008 memoir, was an F.D.R. quotation pinned to the wall: “We can. We will. We must.” But in Utah, impressed by the generosity of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Harry and Landra Reid converted to Mormonism together. Reid moved to Washington to attend law school at George Washington University, working nights as a Capitol Police officer to pay the bills.

As a young lawyer in Las Vegas, Reid prided himself on taking the cases of society’s underdogs, such as prostitutes and cocktail waitresses. He served on the state’s gaming commission during Las Vegas’ early days as a mecca for gambling (and organized crime). At one point, Reid wore a wire for an FBI sting of a would-be casino operator; after the agents burst into the room, Reid put the man in a chokehold and hollered, “You son of a bitch, you tried to bribe me!” On other FBI wiretaps, a mobster boasted that he had “Cleanface”—Reid—in his pocket. Reid was investigated, but never implicated in mob activity. Near the end of his tenure on the commission, Landra found a bomb wired to the engine of the family station wagon.

As a politician, Reid was, by his own admission, uninspiring. After serving in the state legislature and as lieutenant governor, he lost a long-shot Senate race, then successfully ran for the House of Representatives and U.S. Senate. His voice was quiet and high-pitched, and he had a tendency for malapropisms. He wasn’t much for glad-handing and kissing babies. It took intense focus to get from Searchlight to the Senate, and perhaps for that reason, he disdained what he viewed as time-wasting niceties—from Christmas cards to state dinners. Typical phone calls would begin without small talk and end as soon as he believed the conversation was finished—he even hung up on President Barack Obama. Reid’s staff was close-knit and fiercely loyal, but he prided himself on not being managed by them. His press secretaries lived in a perpetual state of high anxiety, awaiting his latest unscripted flub.

Reid began his career as a conservative Democrat from a rugged, mostly rural state. He was anti-abortion, pro-gun and hawkish on legal and illegal immigration. Reid was the first Democrat to come out in favor of the first Gulf War, under President George H.W. Bush, and voted in favor of the Iraq War in 2003. But his politics evolved alongside his native state. Nevada in the 1990s experienced vertiginous growth, as gambling and tourism fueled the rapid growth of an increasingly diverse population and a housing boom. By the end of his career, Reid was an avowed environmentalist, a pro-gay-marriage ally of Planned Parenthood who championed (unsuccessfully) immigration and gun-safety reform. He viewed the vote for the Iraq War as his greatest regret.

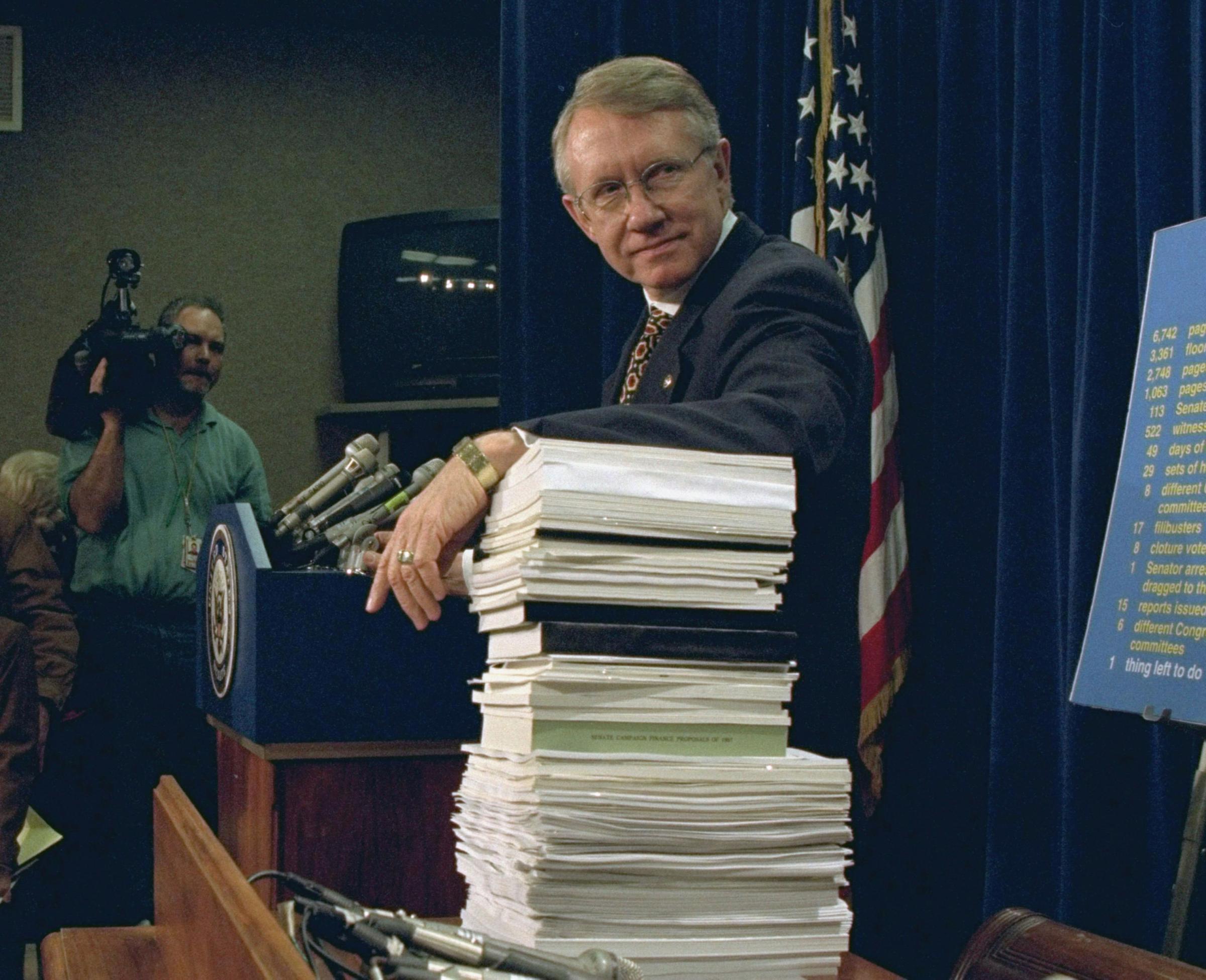

The self-aware Reid knew his greatest strength was not soaring rhetoric but the inside game. He had a photographic memory and a preternatural talent for favor-trading. These traits served him well as he rose in Democratic Senate leadership to become the party’s whip, or vote-counter: He kept a handwritten list in his jacket pocket listing each Democratic senator and what they wanted. Even on the other side of the aisle, he knew the pressure points: In 2001, he convinced Vermont Sen. Jim Jeffords, then a Republican, to switch parties and caucus with the Democrats by offering Jeffords the chairmanship of the environmental committee that Reid then held. Jeffords’ switch swung the Senate to the Democrats, the only time in history that a party switch shifted control of the chamber.

Reid’s ascent to majority leader was somewhat accidental. He became minority leader after South Dakota Sen. Tom Daschle was unexpectedly defeated in the 2004 election, and majority leader after the Democratic wave election of 2006. (Watching the returns roll in, the usually unsentimental Reid was so elated he kissed the television.) Early on, Reid saw promise in Obama, then a junior colleague, and encouraged him to run for president in 2008. After Obama was elected, Reid shepherded his major legislative accomplishments through the Senate, including the 2009 stimulus bill, the Dodd-Frank banking reforms and the Affordable Care Act.

Reid’s state was perhaps the hardest hit in the nation by the 2008 crash. Boom turned to bust practically overnight. The sudden evaporation of the housing market turned Las Vegas into a graveyard of half-built casinos and housing developments. When the casino company MGM was in danger of bankruptcy, Reid personally harangued and threatened its creditors and got them to pull back, he later admitted. For his 2010 reelection campaign, he built a formidable political machine to defeat the Tea Party darling Sharron Angle—despite his personal unpopularity and a national GOP wave. Reid played hardball, freezing out his own son when he ran for governor against his father’s wishes; he locked up the state’s donor establishment and powerful labor organizations and devoted unprecedented attention to mobilizing the growing Hispanic community.

The Reid machine is still cranking in the Silver State, a onetime GOP bastion that now boasts two Democratic senators and has gone blue in the last four presidential elections. Reid also took pride in boosting his state’s prominence on the national political stage. In 2008, he muscled Nevada onto the early presidential nominating calendar, after Iowa and New Hampshire, where it has remained ever since.

Reid’s tenure wasn’t a necessarily a happy time in the U.S. Senate. His relationship with his Republican counterpart, Mitch McConnell, was so poisonous that McConnell in later years would only negotiate with Biden, then the vice president. Reid blamed McConnell for abusing procedure to relentlessly block Obama’s appointments and agenda. (McConnell’s allies said it was Reid who started the spiral of obstruction in the George W. Bush years). In November 2013, Reid deployed the so-called “nuclear option,” changing Senate rules to eliminate the 60-vote threshold for most nominations. Some observers say that change paved the way for McConnell, in 2017, to go further and get rid of the threshold for the Supreme Court, allowing President Donald Trump’s three nominees to be seated by narrow margins. Reid’s domineering style and the gridlock he presided over exasperated many fellow Democrats.

More from TIME

Reid’s health began to decline in 2015, when an accident involving an exercise band left him blind in one eye. He announced his retirement and anointed a successor. Buoyed by the Reid machine, Democrat Catherine Cortez Masto would become the only swing-state Democrat to win in 2016 and the nation’s first Latina senator. He watched the politics of the ensuing years with a mixture of detachment and disgust, telling the New York Times that he found Trump “amoral” and considered him the worst president ever. In May 2018, he was diagnosed with one of the deadliest cancers, pancreatic, a diagnosis he received matter-of-factly, as if it only validated his lifelong fatalism. In his later interviews, he described his legacy as having done what had to be done, whatever the cost.

“I wasn’t the leader of the Senate because I was tall, dark, and handsome, [or] articulate,” he told the Nevada journalist Jon Ralston in January 2018. “I did things no one else would do.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com