After six years of Marwand’s living in America, his homecoming to Afghanistan is not off to a great start. Nearly as soon as the 12-year-old boy returns with his family to their relatives’ compound in the rural province of Logar, the venerable yet vicious guard dog, Budabash, bites off the tip of Marwand’s index finger. “For the next few weeks,” Marwand tells us, “I called a jihad against Budabash. Until, of course, about 31 days later, when he got free.” With his young relatives Gul, Zia and Dawood in tow, Marwand sets off into the countryside to try to recover the dog before nightfall.

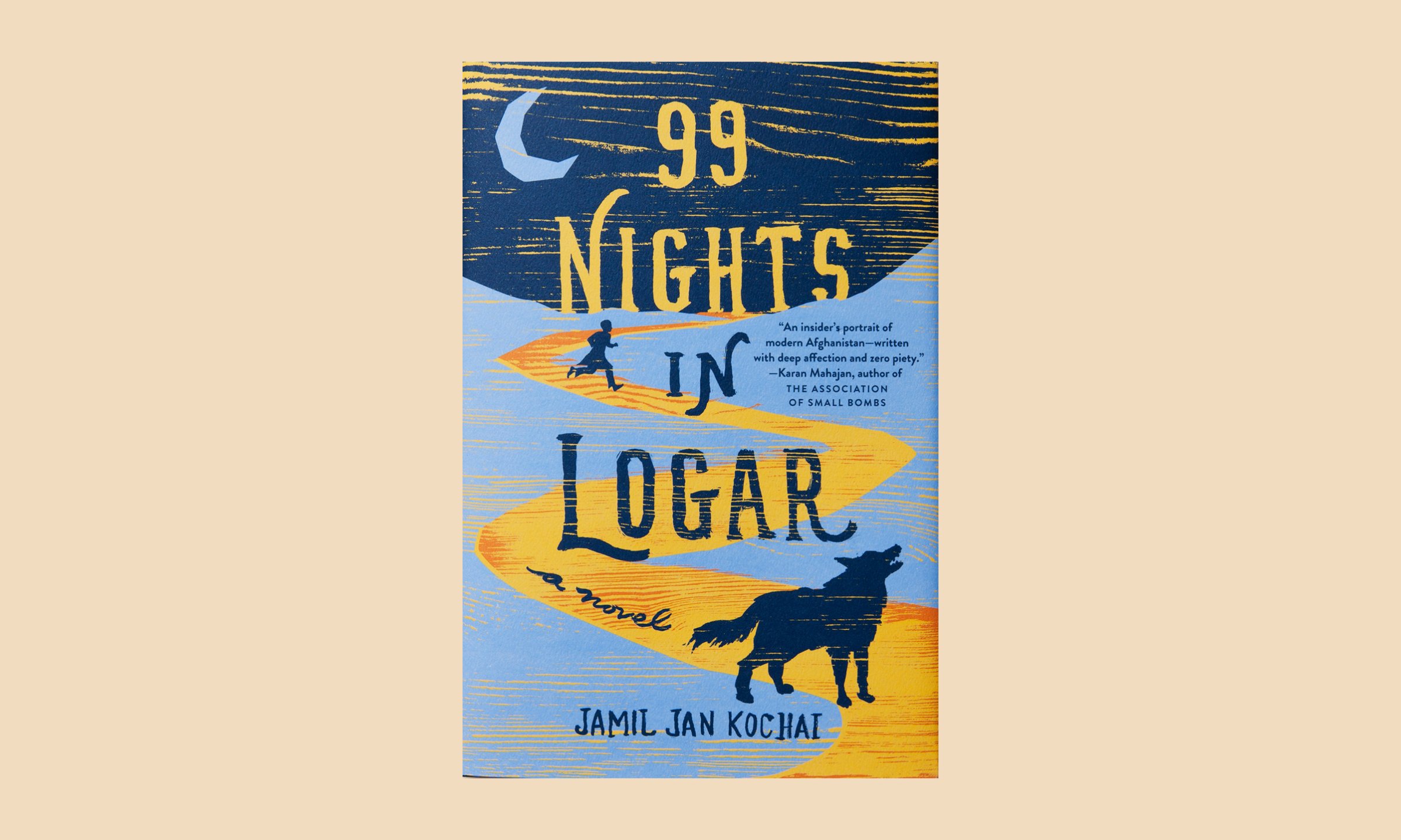

The opening of Jamil Jan Kochai’s debut novel 99 Nights in Logar may feel like the beginning of a comfortably familiar story: a ragtag group of kids on a forbidden adventure like something out of The Goonies or Stand by Me. But as this band advances through the vivid landscape of desert, mountains, canals and a near impenetrable maze of clay compounds that recalls the Minotaur’s labyrinth, we learn that we are not reading a simple story, nor a single one. Instead, Kochai, who was born in Pakistan and raised in the U.S., weaves together a tapestry of stories to present a captivating image of the country that has been called “the graveyard of empires.”

Archetypal characters like the thief and the solider drift in and out as the search for Budabash is sidetracked by other misadventures. Throughout Marwand’s time in Logar, he and the other characters swap stories, which appear in the text under their own headings, such as “The Tale of the Butcher’s Son,” “The Tale of the Bibi and the Flood” and “The Tale of the Old Dog.” For the characters, these tales are not mere entertainments, but rather ways of understanding their often war-shattered world, the enactment of collective memory that creates a family, and a nation. For American readers, they are a way into a culture too often reduced to stereotypes.

Kochai maintains a playful humor in Marwand’s voice, channeling something like One Thousand and One Nights meets The Sandlot, and we feel as if we are watching the coming-of-age of a real boy. Yet, especially in its second half, the novel departs from realism into the hazy lyricism of mythmaking on the way to its affecting conclusion. Its final meta-story is introduced in English as the tale of a deceased ancestor whose memory has loomed over the entire narrative, then rendered entirely in Pashto. English readers may not understand the words, but they can comprehend Kochai’s message–a bulwark against exoticism that reminds us that if we can treat stories with respect, we have a better chance of respecting the lives those stories serve.

Mancusi’s debut novel, A Philosophy of Ruin, will be published in June 2019.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com