Wildfires are notoriously unpredictable, but that hasn’t stopped Los Angeles Fire Department Chief Ralph Terrazas from spending much of his career trying to outsmart them. As a battalion chief more than 20 years ago, Terrazas was asked to figure out how fast wildfires move. His solution, for which he now holds a patent: a triangular piece of Plexiglas, which firefighters could overlay onto the department’s 800-foot maps to estimate a brushfire’s progress over the next hour-and-a-half.

“It was cumbersome,” says Terrazas, 58, whose department is responsible for protecting 4 million people and 150 square miles of territory, much of it brush vulnerable to blazes that could threaten the city. “But prior to that we had nothing.”

By 2015, Terrazas had become chief, but his department was still mapping wildfires with pencils and his glorified protractor. That, however, was about to change. While reading an in-flight magazine, he came across an article about computer scientist Ilkay Altintas and her team at the San Diego Supercomputer Center at the University of California San Diego. The article detailed Altintas’ work on a cyber-infrastructure system called WIFIRE, which was designed to predict a wildfire’s path in real time. Once back on the ground, Terrazas drove down to San Diego to meet Altintas’ team. Within a week, a firefighting partnership was solidifying, and Altintas was conducting aerial observations from LAFD helicopters. Today, WIFIRE is used by the LAFD, as well as the Los Angeles County Fire Department, the Ventura County Fire Department, and the Orange County Fire Authority; about 120 other groups across California are testing it.

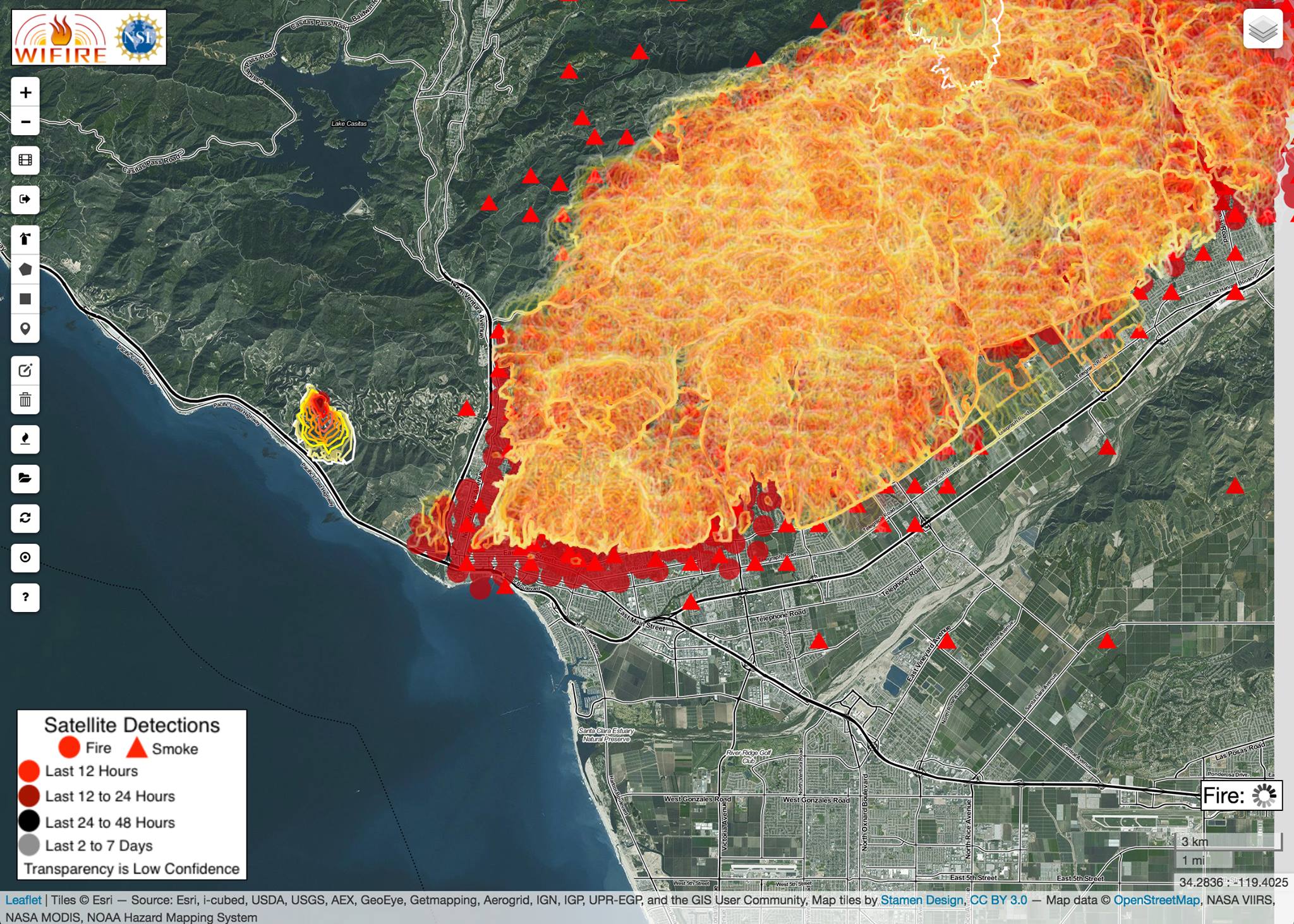

Knowledge of the fuel sources in a wildfire’s path is critical to predicting its movements. An area of dry brush will burst into flames when lit, while a well-watered golf course can halt a fire in its tracks. To that end, WIFIRE’s artificial intellingece software examines high-resolution satellite imagery to predict the combustibility of the vegetation surrounding a fire, then incorporates that information into its predictions. Because factors like wind and precipitation can also affect a fire, real-time weather information is fed into the system as well. (A separate program, which serves as an early warning system, identifies smoke plumes from cameras high on mountainsides, no easy feat in images often containing fog or clouds.)

“During a fire, there is so much information coming your way. There needs to be a simple way to access the data,” says Altintas, who helped develop the system’s firemap tool, which visualizes the model’s projections for responders. “[Firefighters] can put a pin on where the fire ignition point is, set the parameters … and model the fire with the click of a button.”

The backbone of the WIFIRE system is a combination high-speed fiber optic and fixed wireless network that connects the San Diego supercomputer center with hundreds of remote weather stations across the county. (A similar system is being extended to the rest of California.) The high-resolution weather data provided by that system helps WIFIRE’s modeling program predict how a fire will spread in real time. The system also allows responders to prepare for fires before they occur by running simulations of possible fire scenarios, allowing firefighters to spot potential vulnerabilities before they flare up. It’s all a far cry from mapping fires with a Plexiglas triangle.

As wildfires increasingly threaten people and property near Silicon Valley’s best and brightest, WIFIRE has emerged as just one tech-savvy response to the threat. And at a time when artificial intelligence programs are doing everything from selling deodorant to swinging elections, WIFIRE’s researchers say their project shows a different side of the emerging technology. “There is definitely a social good aspect to machine learning, and I think this is a very good example of that,” says Altintas.

Of course, even the most useful tools have their limitations. Even with the latest modeling technology, wildfires remain unpredictable. Wind-blown embers can cause fires to spread faster than anticipated or even hop natural or man-made barriers, a behavior that models have a hard time capturing. “Ultimately there is no magical solution,” says Jonathan Sury, an expert in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) at Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness. “Tools like this are decision-support tools, and they should be used as one piece of information among many others.”

In the case of the Camp Fire, which killed dozens of people in and around Paradise, California last year, Chief Terrazas doubts that WIFIRE, which wasn’t used in fighting that blaze, could have made a noticeable difference. Factors like building construction methods and materials, brush clearance, and lack of egress roads all may have played a part in the disaster. Having more firefighters on scene might have helped, too. “You have to have the resources available,” says Terrazas. “If they told you the projection, you still would need the firefighters to do something with that information, and they were just overwhelmed [in Paradise].”

What WIFIRE offers is information that can help fire departments deploy their limited resources more effectively. And as wildfires stand to become more numerous and destructive amid a changing climate, firefighters need any advantage they can get. “Historically we’ve treated these as kind of extreme events as outliers,” says Sury. “But now they are more common and they are going to become more common over time.”

WIFIRE was funded by a $2.6 million grant from the National Science Foundation, but that financial support has recently reached its scheduled end date. Altintas needs about $200,000 per year to maintain WIFIRE. The LAFD, along with the Los Angeles County Fire Department, the Ventura County Fire Department and the Orange County Fire Authority have each pledged to contribute $25,000 a year to keep the system operational, and they hope to secure the rest of the funding from the state government. “I told [Altintas] ‘this can’t end,'” says Terrazas. “In light of all the fires we’ve had, its value is only increasing.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Alejandro de la Garza at alejandro.delagarza@time.com