Arrested by the Nazis in 1937 for his defiance of Hitler, Pastor Martin Niemöller spent three and a half years in solitary confinement in Sachsenhausen concentration camp before being moved to the Dachau camp in 1941, where he was housed with other high-profile non-Jewish prisoners, including foreign dignitaries and Catholic clergy. There, on Christmas Eve 1944, Niemöller preached a sermon to a half dozen fellow Protestant inmates. It was the first religious service the Nazis allowed Niemöller to conduct since his arrest.

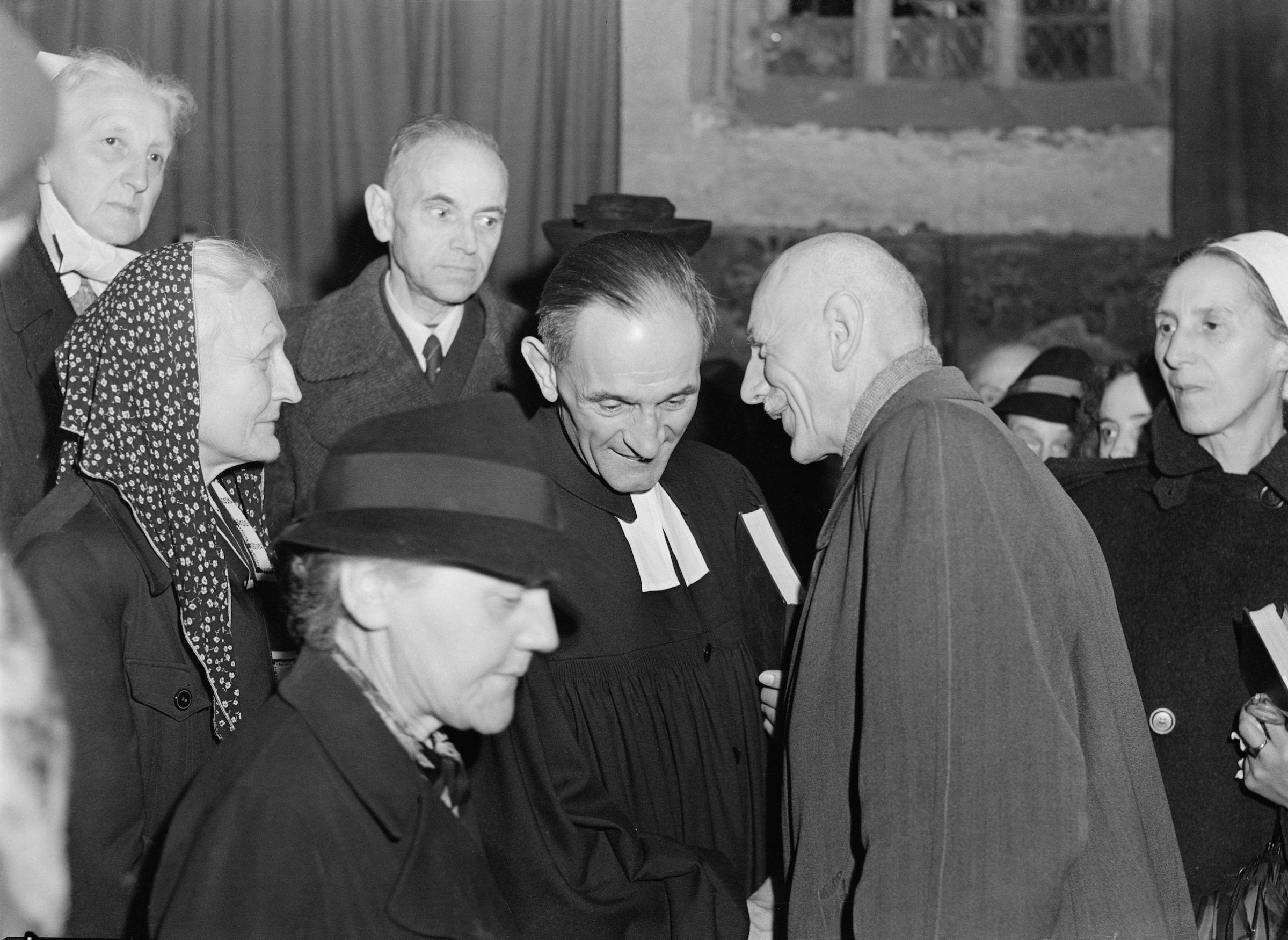

At first, Niemöller was hesitant about offering a service, knowing that his country was at war with the nations from which these other political prisoners came. He asked each of them privately if they wanted him, a German and a Lutheran, to conduct the service. Their insistence inspired and moved him. His “congregation” that Christmas Eve was unique in Niemöller’s experience — it was multinational and multidenominational, consisting of a Dutch cabinet minister, two Norwegian shippers, a British major in the Indian army, a Yugoslav diplomat and a Macedonian journalist. The appointed date for the service was the last day of Advent, December 24, the traditional day on which Germans celebrate the birth of the Christ child. For Martin Niemoller in 1944, it was the eighth Christmas he would not celebrate with his own wife and children.

Crowded into cell number 34, which had been consecrated as a chapel by imprisoned Catholic clergy, the pastor acknowledged the fear and uncertainty they all felt as Allied bombs rained down on German cities and Hitler urged his soldiers, old men and boys in some cases, to fight to the last man. Niemoller himself had lost one daughter and one son, ages 16 and 22, in the war. Despite the bleak and lonely circumstances, he counseled his fellow worshippers to rejoice in their common faith that God had built a bridge to the world — even to Dachau — through the birth of his son Jesus Christ.

Priests and pastors the world over have preached similarly on Christmas Eve, although not from behind barbed wire. But in Niemöller’s case the Christmas Eve service in Dachau signaled the beginning of a profound shift in his outlook — a shift from believing in a German national Protestantism to believing in an international world Protestantism.

The acknowledgment that the Gospel, the good news of Christ’s love and mercy, was for all of humankind — not only for Germans — represented a symbolic first step in the moral and political evolution of Martin Niemöller.

Niemöller was not in the habit of celebrating the Lord’s Supper with Anglican, Calvinist and Greek Orthodox Christians, much less Slavs. An ardent nationalist and devout Lutheran much of his life, Niemöller had proudly served as a German naval officer in WWI, fought with right-wing paramilitaries against Communist insurgents in 1920, and voted for the Nazis in 1924 — the same year as his ordination. Forty-one years old in 1933, he was euphoric when Adolf Hitler became chancellor, believing that the marriage of National Socialism and German Protestantism would bring his beloved nation the providential glory it deserved.

In order to win votes and consolidate his power, Hitler promised to work harmoniously with the Lutheran clergy to achieve national and moral renewal. But Hitler’s real intention became clear when Nazi officials began to meddle in church affairs and he supported a faction called the German Christian Movement that wanted to Aryanize the church by abolishing the Old Testament, worshiping an Aryan Jesus and banning Christians with Jewish ancestors.

Despite Niemöller’s deeply ingrained nationalism and anti-Semitism, he could not countenance such heresies in his church. He, along with Dietrich Bonhoeffer and others, founded the Confessing Church, which pledged to adhere to the gospels and defend Protestants with Jewish ancestry. Although Niemöller’s leadership of the Confessing Church put him at odds with the Nazis on church matters, he still considered Hitler to be Germany’s political savior and remained committed to the Nazi party’s program, which included national revival, territorial expansion and fighting so-called “Judeo-Bolshevism.” Unlike Bonhoeffer, whom the Nazis would execute in April 1945 for his resistance to Nazism, the former U-boat commander still displayed little interest in international fellowship or ecumenism.

But Niemöller’s concentration camp experiences changed him. In Dachau, where Niemöller was allowed to socialize with other special prisoners, he developed a camaraderie with Catholic priests, French politicians, British officers and others. They shared something in common now—their persecution at the hands of the Nazis. Outgoing and friendly by nature, Niemöller thrived in this setting after the years in solitary confinement. And the international and multi-denominational fellowship Niemöller experienced in Dachau turned him toward the possibility of a world fellowship in the Holy Communion, not just a German fellowship in national Protestantism. The international contacts he made in Hitler’s camps and in the immediate months following his liberation urged him to lead his country in repenting for the atrocities and crimes committed in their name.

Niemöller came to believe that he and his fellow countrymen who had supported Hitler, even while disagreeing with aspects of his rule, had a moral obligation to acknowledge their guilt, repent and change their ways. He did this by setting an example. He confessed his own guilt to German audiences repeatedly in 1946 in what is now known as the Niemöller Confession: “First they came for the Communists, and I did not speak out — Because I was not a Communist. Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out — Because I was not a Trade Unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out — Because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me — and there was no one left to speak for me.”

And his evolution didn’t stop there. The 1950s, ’60s and ’70s would see further changes as he embraced pacifism, marched for left-wing causes and became a vocal critic of racism and bigotry. On his 90th birthday Niemöller joked that he had started his political career as “an ultraconservative” who loyally served the kaiser. Now I’m “a revolutionary,” he said. “If I live to be 100, maybe I’ll be an anarchist.” But anarchism wasn’t in the cards. The journey he began in Dachau came to an end with his death in 1984 at the age of 92, after four decades of preaching the message of world fellowship he articulated for the first time in Dachau.

Matthew Hockenos is Harriet Johnson Toadvine ’56 Professor in Twentieth-Century History at Skidmore College and the author of Then They Came For Me: Martin Niemöller, the Pastor Who Defied the Nazis, available now from Basic Books.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com