Gene Autry sang about Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer as “the most famous reindeer of all” — and there are numbers to back him up. The “Rudolph” song topped the charts in 1949; the stop-motion animated version of his story, which premiered in 1964, is known as the longest-running Christmas TV special; and a recent Hollywood Reporter/Morning Consult poll declared it the “most beloved holiday film,” picked by 83% of respondents.

But in recent years, Rudolph has become famous for a less happy reason.

This year, for instance, some viewers of the 1964 TV special observed what the Huffington Post called, semi-jokingly, “seriously problematic” behavior in certain scenes in which Rudolph is bullied because of his nose; the Huffington Post video montage of these comments has racked up nearly 6 million views in a little over two weeks. The View also debated the issue — though it’s exactly not a new “issue.” In 2013, The New Republic described the story as depicting “a dystopia where affection is based on economic worth” and “a fairly grim, Hobbesian vision of society.”

“Give me a break,” Barbara May Lewis, the daughter of Rudolph creator Robert L. May, recently told TIME when asked what she thought of the critiques. “The controversy makes no sense to me. The book itself had very little to do with it [the TV special], and it wasn’t lauding bullying.”

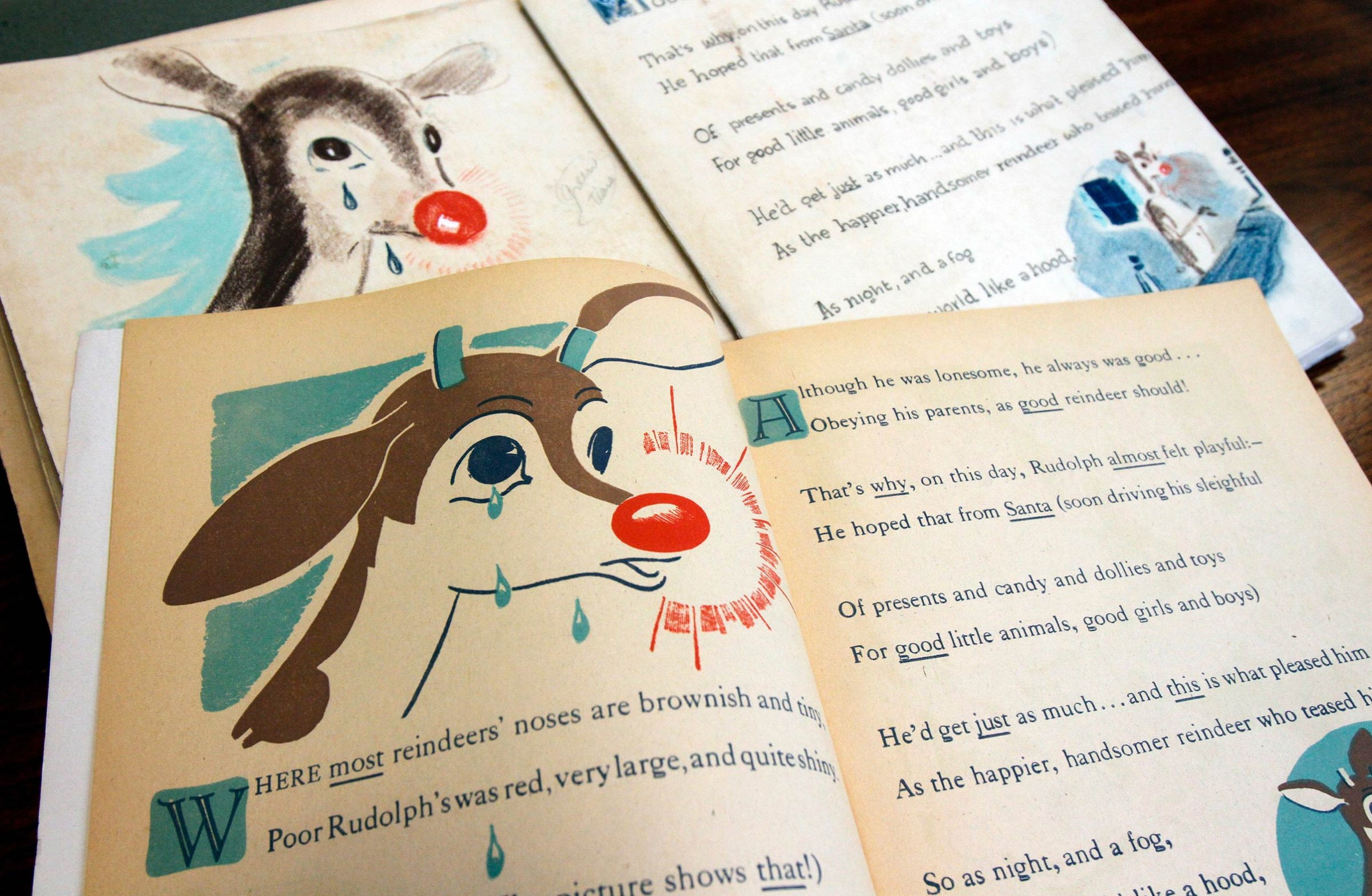

In fact, she says, the story of Rudolph is sad, but for a different reason — because her father was “a sad guy” when the Chicago copywriter was asked by the retail and catalog company Montgomery Ward to create a brand-new character for its annual promotional coloring booklet for Christmas. He came up with the story of a reindeer with an abnormally large, shiny, red nose who gets teased by the other black-nosed reindeer. But on a foggy Christmas Eve, Santa realizes Rudolph’s glowing snout is the beacon he needs so that he can deliver presents to children on time.

Despite its fantastical holiday elements, the story was partly based on some of May’s past experiences. The character of Rudolph who is “shunned by others but vindicated some way in a happy ending” was inspired by the story of the Ugly Duckling, which May later wrote had always appealed to him as someone who, growing up, was a “shy” and “small” boy, and who “had known what it was like to be an underdog.”

May was feeling downtrodden about his present life, too. “‘And how are you starting the new year?’ I glumly asked myself,'” he later recalled, describing his mindset in early 1939 when he first received the assignment. “Here I was, heavily in debt at [nearly] 35, still grinding out catalogue copy. Instead of writing the great American novel, as I’d once hoped, I was describing men’s white shirts.

He was also feeling “glum” in 1939 for a more serious reason. He was writing the descriptions of a weeping, “lonesome” reindeer as his wife was dying. In a 1975 article for the Gettysburg Times, he described going to work on a windy, icy-cold January day and feeling “relieved” that holiday street decorations by Montgomery Ward had been taken down. “My wife was suffering from a long illness and I didn’t feel very festive,” he recalled.

Meanwhile, May kept working. He figured the story should be about a reindeer because images of Santa’s reindeer already everywhere during the Christmas season, and his toddler daughter was obsessed with the deer at Lincoln Park Zoo. Though Santa’s reindeer already had names — Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donner and Blitzen, thanks to the 1820s poem “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” — May came up with a ninth for the list. He brainstormed a list of names that began with the letter “R” for “alliterative purposes,” such as Rollo, Rodney, Roland, Roderick and Reggy. (That list is now held at May’s alma mater Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., with the rest of his papers.) In a 1963 interview, he said he thought Rollo sounded “too happy for a reindeer with an unhappy problem” and Reginald “seemed too sophisticated,” but Rudolph “rolled off the tongue nicely.” As for the idea of a glowing nose apt for navigating, that light-bulb moment came from looking out his office window in the middle of one of Chicago’s infamous winter days, seeing the fog from Lake Michigan and thinking of Santa trying to do his work on such a night. (The idea almost got shelved, May would note, after focus group participants said they thought a red nose had “connotations of alcoholism.”)

As the pages were coming along, his wife’s condition worsened.

“Spring slipped into summer. My wife’s parents came to stay with us to help,” he later wrote. In July, she passed away. His boss gently offered to pass the assignment off to someone else. “But I needed Rudolph now more than ever. Gratefully I buried myself in the writing.”

About a month later, before submitting the draft, he read it to his daughter Barbara and his in-laws in the living room. “In their eyes I could see that the story accomplished what I had hoped,” he said in 1975.

Montgomery Ward printed the story as a soft-covered booklet in 1939 and distributed 2.4 million copies for free. Then, the small publishing house Maxton Publishing Co. offered to print it in hardcover. It became a best-seller, but Rudolph’s story didn’t really become world-famous until May’s brother-in-law Johnny Marks wrote the musical version that Gene Autry sang. The tune topped the charts in 1949. “I don’t think it ever would have had the coverage if it weren’t for the song,” Lewis says.

And, just as Rudolph helps families have a happy Christmas in May’s story, Rudolph the brand helped the May family get through a tough time.

When May died in 1976 at the age of 71, TIME’s obituary noted that he had received royalties on more than 100 Red-Nosed products, as well as the song, since Ward let him have the copyright in 1947. By 1985, the song had sold 150 million records and 8 million sheet music copies worldwide, and when the puppets in the 1964 TV special were up for sale last year, bids went as high as $10 million. The song was also a favorite in the Nixon White House, as the first Christmas song that first daughters Tricia and Julie learned to sing.

Lewis, 84, who would become a copy editor, says the story influenced her own career path, as she remembers suggesting her father describe Santa’s stomach as a “tummy” because it sounded better in the following line: “This fog, [Santa] complained, will be hard to get through / He shook his round head. (And his tummy shook too.)”

While the story certainly made May a lot of money, “enough to get me out of debt” and put his own children through college, he later said, it also provided a valuable lesson for all children as a “story of acceptance,” the moral of which was that “tolerance and perseverance can overcome adversity.”

Nearly 80 Christmases after he was first introduced, Lewis thinks the story of Rudolph can still inspire people who don’t feel like they fit in. “Rudolph was made fun of, but he took his difference and made good use of it,” she tells TIME. “He didn’t let it get him down. It didn’t get in the way when it came time to shine.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com