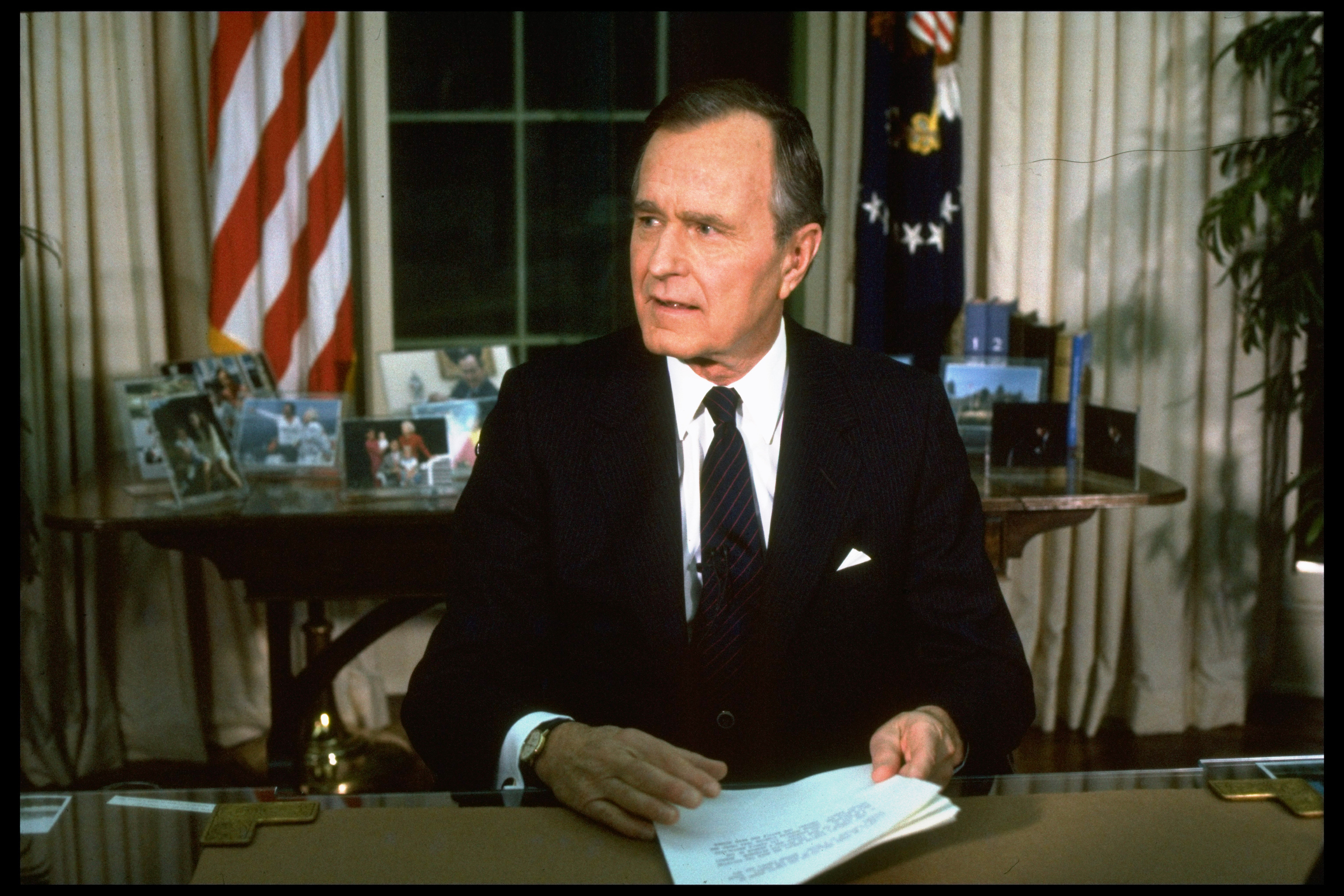

The United States has had only 45 presidents over its two and a quarter centuries as a nation, and we just lost one of them: George H.W. Bush, the 41st. Of course we will and should mourn, but we would be remiss if we did not as well take a few moments to learn from his four years in the Oval Office and from the other 90 years of his remarkable life.

First and most important, we should see that people matter. There is little about history that is inevitable. No two people given the same situation would choose to do the same things, much less do them in the same way.

For example: When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1990, some said it was unfortunate but tolerable. Others (including nearly a majority in the U.S. Senate) argued it was intolerable but not worth fighting over, that we should give economic sanctions more time to work even though there was little reason to believe that they would ever persuade Saddam to give up most, much less all, of his conquest.

Bush disagreed, suggesting that if much more time passed there would be no Kuwait left to save. He also maintained that at stake was not just energy supplies critical to the global economy but the character of the emerging post–Cold War world, and that if this aggression were allowed to stand it would soon be followed by aggression elsewhere.

Bush dispatched half a million American soldiers to the Persian Gulf, and after diplomacy failed to persuade Saddam to exit Kuwait, ordered them and their counterparts from the international coalition he had assembled into battle. Military success was quick to come and, fortunately, came at a cost that was relatively low — indeed, far lower than many had predicted. It is difficult to imagine the world would be in better shape today if tyranny and aggression had been allowed to prevail.

Implicit in the above is the lesson that the United States cannot turn its back on the world without paying a price. Bush fought in World War II, at 18 — the youngest American fighter pilot in the war. He understood that isolationism is folly, that the United States cannot insulate itself from the economic, physical and human consequences of a world that comes apart.

But while there has been no substitute for U.S. leadership, the United States also could not go it alone. Unilateralism is no more viable than isolationism. In the Gulf War, the United States benefitted from foreign military contributions, access to military bases, financial assistance and the support built by the diplomacy that came before and after the conflict. Multilateralism and the nation’s security can, and often do, go hand in hand.

Again, this need for partners is, if anything, truer today. So many of the challenges defining and threatening today’s world — from climate change and terrorism to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, protectionism and disease — cannot be managed, much less solved, by any country acting alone, even one as powerful and wealthy as the United States.

There are as well personal lessons to be learned from the life of the 41st president. One is the importance of small gestures, of hand-written notes in this time of emails and tweets. Bush also exemplified the notion that there is nothing you cannot accomplish if you don’t care who gets the credit; modesty can bring rewards.

Bush understood that while he was the president, his hold was temporary, and that the office was more important than any personal or political consideration. Everything about him was consistent with the notion that public service was a noble calling and that politics need not be a blood sport. Politics can bring us together. But that requires a willingness to compromise, to see those on the other side as opponents — not enemies — and to choose the public good over the personal.

Bush did just this when, in 1990, he went against his campaign pledge not to raise taxes. By agreeing to a small increase in the personal rate, he made a bipartisan deal possible, one that cut spending and put the U.S. economy on a trajectory that in the years to come would help raise economic growth and, eventually, eliminate the deficit.

Bush paid a large political price for this decision. It triggered challenges from within the Republican party and from a third party in the 1992 general election that helped pave the way to Bush’s defeat by Bill Clinton.

But, as was typical of George H.W. Bush, he accepted this defeat with grace. He did not challenge the vote count or the legitimacy of a political system he revered. He let the man who was to become the 42nd president know he was rooting for his success. And after Clinton too concluded his presidency, the men found ways to travel the world together to help people in need and to send the message that shared love of country could and should take precedence over all else.

Yes, let us mourn the passing of the 41st president. But let us also learn from his life.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com