Everybody who’s decorating for Christmas knows to do so with red and green. But the story of how red and green came to represent Christmas isn’t as linear as the string lights around your tree.

Yes, certain traditions of the holiday, like the green of mistletoe and the red of Santa’s garb, might seem like obvious sources for the tradition. But it’s not quite that simple, according to Arielle Eckstut, author of The Secret Language of Color. “There is no definitive history, per se,” she tells TIME.

Eckstut’s research found that holly, with its green leaves and red berries, long played a role in winter solstice celebrations that predate the spread of Christmas. But despite those deep roots, it would take centuries for the link between Christmas and those colors to become as solid as it is today in American culture. But, Eckstut says, one reason for that shift is clear: advertising.

“It’s like a lot of things that have to do with culture and color, where it’s some combination of a natural phenomenon mixed with other cultural forces,” she says.

The cultural forces here? Particular credit goes to 1930s Coca-Cola advertisements that featured paintings of Santa Claus as we know him: old, plump, jolly, red-faced and white-haired, with a red outfit to boot. This depiction of Santa didn’t really exist in collective cultural consciousness before the soda company’s advertisements, Eckstut says.

After a 1930 campaign used images of what was clearly just a regular man in a Santa costume, rather than an image of the “real” Santa, Archie Lee at the D’Arcy Advertising Agency wanted something more wholesome and genuine, according to Justine Fletcher, director of archives for Coca-Cola. The company commissioned artist Haddon Sundblom to paint this new kind of Santa in 1931.

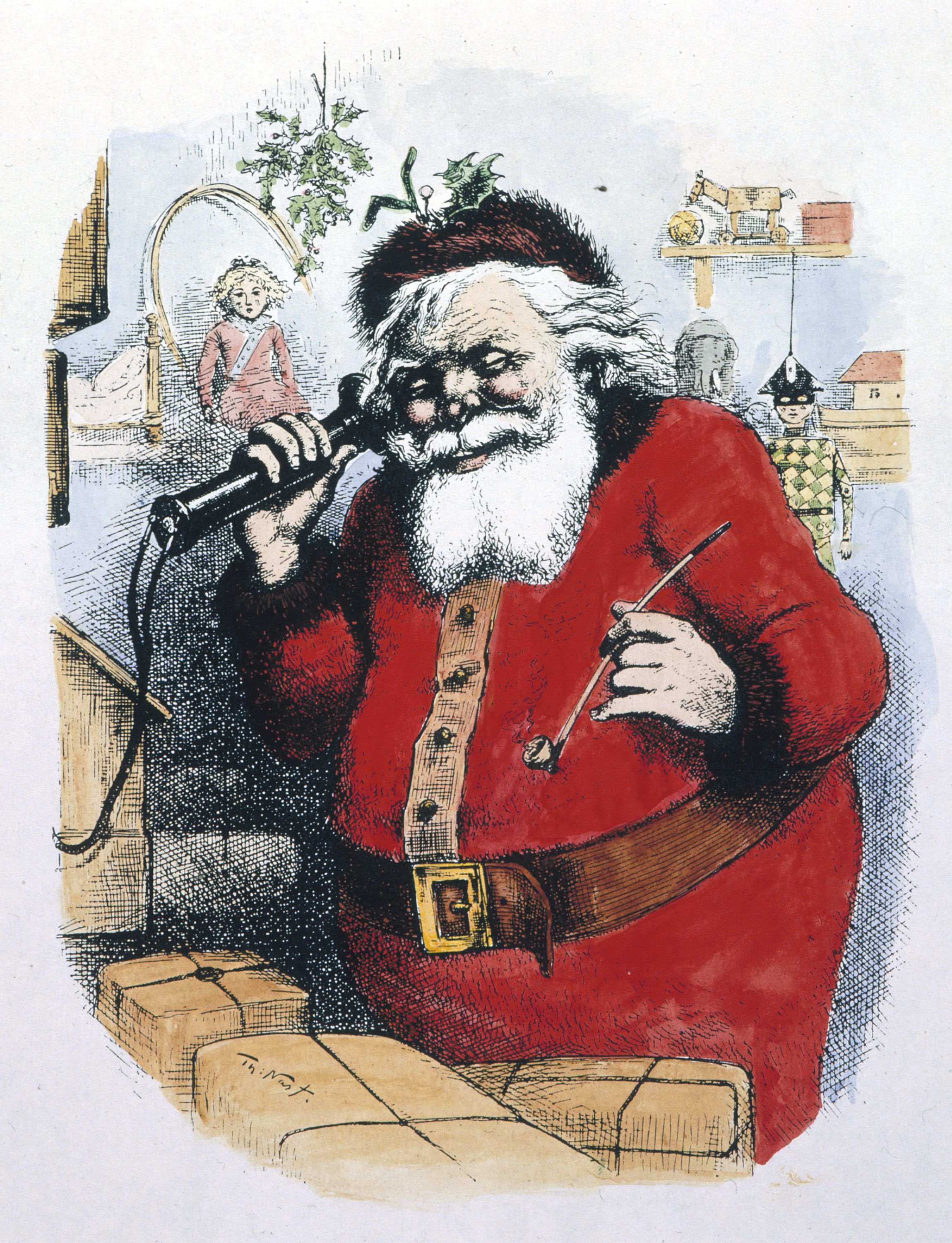

With a vision of Santa Claus based on imagery in the poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas” — colloquially known by its first line, “‘Twas the night before Christmas” — by Clement Clarke Moore, Sundblom created a jolly Saint Nick. Sundblom was not the first to imagine Santa that way. For example, political cartoonist Thomas Nast drew Santa for an 1862 issue of Harper’s Weekly, and the two images are quite similar. But the staying power of the Coke ad proved nothing short of magical, and Sundblom continued painting annual Santa Claus ads for the brand until 1964. “That Santa that Sundblom did became in people’s minds what Santa looked like,” Fletcher tells TIME.

Another element of the image proved enduring, too: the red colors of Santa’s clothing alongside the green of a Christmas tree.

“I like to say it’s the beauty of nature combined with the crassness of commerce that created a red and green Christmas,” Eckstut says.

It’s no coincidence that the seasons are color-coded — or that there’s a similar story behind Hanukkah’s colors of white and blue. Eckstut’s research shows that people are biologically programmed to want to learn and understand the world through color. We know when a piece of fruit is ripe enough to eat because of its color; we know when grass becomes too dry because of its color; we don’t often like to eat blue foods, because a lot of blue in nature exists in poisonous plants. So we yearn for these kinds of cues to exist in society, too, Eckstut argues.

“Color has always served as a map,” she says. “Culturally, we want that as well.”

This biological explanation may also play a role in why green and red helped make Christmas one of the most recognizable and celebrated holidays in the world — those two colors, complements on the color wheel, are aesthetically pleasing. “Naturally, your eye is drawn to those beautiful red berries and the green leaves,” Eckstut says.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Rachel E. Greenspan at rachel.greenspan@time.com