This week marks 50 years since President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Gun Control Act of 1968 into law on Oct. 22 of that year. It was the first major gun control measure in the United States in 30 years, but its passage earned this dismissive take in the pages of TIME: “better than nothing.”

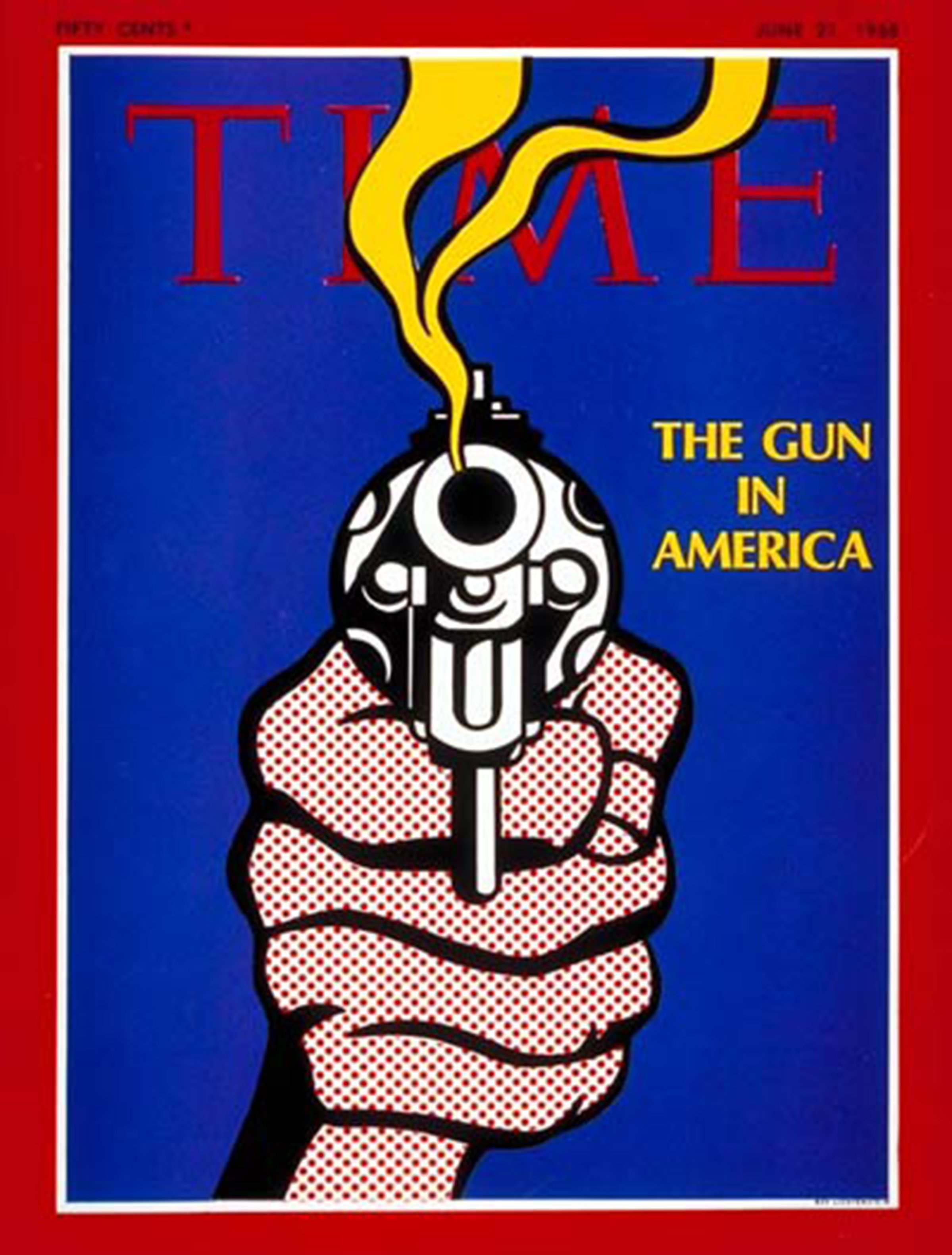

“Forget the democratic processes, the judicial system and the talent for organization that have long been the distinctive marks of the U.S. Forget, too, the affluence (vast, if still not general enough) and the fundamental respect for law by most Americans. Remember, instead, the Gun,” the magazine had noted earlier that year, in a cover story about the role of guns in the United States, which was prompted by the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy. “All too widely, the country is regarded as a blood-drenched, continent-wide shooting range where toddlers blast off with real rifles, housewives pack pearl-handled revolvers, and political assassins stalk their victims at will. The image, of course, is wildly overblown, but America’s own mythmakers are largely to blame. In U.S. folklore, nothing has been more romanticized than guns and the larger-than-life men who wielded them. From the nation’s beginnings, in fact and fiction, the gun has been provider and protector.”

Though the 1968 law was a victory of sorts for gun-control activists, many were disappointed it didn’t include a registry of firearms or federal licensing requirements for gun owners. TIME reported, “It may take another act of horror to push really effective gun curbs through Congress.”

Those dynamics — the disappointment of gun-control activists, particularly after moments of tragedy, running up against the very real place of guns in American society — may sound familiar. To mark the law’s anniversary, and as TIME once again examines the role of the gun in the nation’s culture, TIME spoke to historian Robert Spitzer, author of five books on gun policy including Guns Across America and The Politics of Gun Control, about that landmark law.

What was going on in the world and the country when the Gun Control Act of 1968 passed?

It had been floating around Congress for several years. [Discussion] really began after the JFK assassination; there was a strong sense that people shouldn’t buy guns through interstate mail, because Lee Harvey Oswald did through an ad that appeared in a NRA magazine. Congress held hearings, but it didn’t really go anywhere. Now in 1968, the country is facing rising urban rioting. In the mid-to-late ’60s, crime begins to increase. There’s greater concern about guns and easy accessibility to guns. Martin Luther King is assassinated in April. In June, Robert Kennedy was assassinated and that was really the final push that brought the law back and got it through Congress.

What are the most important things the law changed?

It banned interstate shipments of firearms and ammunition to private individuals [and] sales of guns to minors, drug addicts and “mental incompetents.” This is the first time you have in law that mentally unbalanced people ought not to be able to get guns — also convicted felons. It also strengthened the licensing and record-keeping requirements for gun dealers, and that was significant because gun dealers were subject to virtually no systematic scrutiny up until this time, although a 1938 federal law did establish a fee they paid to government to be a licensed dealer. It banned importation of foreign-made surplus firearms, except those appropriate for sporting purposes.

How did the NRA react to the law?

The President of the NRA, who had testified before Congress about the bill had said [paraphrasing], ‘We’re not thrilled with this, but we can live with it. I think it’s reasonable.’ The fact that he would concede there’s any such thing as a reasonable gun control legislation — that represented the prevailing point of view of NRA leadership at the time, from 1968 to the late 1970s.

A change of leadership occurred at the NRA’s annual convention in 1977 in Cincinnati. A group of dissidents within the NRA felt the leaders were out of touch, not political enough and that the NRA wasn’t stepping in to defend gun owners, This dissident faction took over, and since then, the NRA became more political. So the 1968 law was part of a larger political process that eventually led to a change of leadership within the NRA. It didn’t result in any political sea change — that doesn’t happen or another decade — but you could point to the law as one factor that eventually causes more dissident gun owners to say, ‘We’re getting beat up, our leaders aren’t doing the right kind of job, and we need a change.’

So how did that larger change eventually happen?

Portions of the ’68 law were modified by a law passed by Congress in 1986, the Firearms Owners Protections Act, which sought to repeal even more of the law. It didn’t succeed, but the 1986 law does repeal or modify or blunt some of the aspects of the ’68 law. [It does that] by amending the ’68 law to allow for the interstate sale of rifles and shotguns as long as it was legal in the states of the buyer and seller, eliminating certain record-keeping requirements for ammunition dealers, and making it easier for individuals selling guns to do so without a license. The 1986 federal law was the culmination of the effort to try to roll back the 1968 law. Reagan is the first president to speak at the NRA’s annual convention, and he was the first presidential candidate ever endorsed by the NRA, although past presidents were NRA members. The NRA didn’t endorse candidates before 1980.

How does the Gun Control Act of 1968 relate to the political debate in recent years, in particular the conversation about mass shootings?

It doesn’t connect up with that phenomenon, which started in 1989 when a gunman shot up an elementary school. [The law] had nothing to say about assault weapons; sales were tiny until the mid 1980s, when the Chinese dumped cheap assault weapons on the American market and sales began to take off.

It seems harder to pass federal gun-control legislation now than it was back then. If that’s the case, why do you think that’s so?

The gun issue hadn’t been politicized in the ’60s the way it has been in the last few decades, where it has become even more angry and strident; 1968 was a year of political assassinations that shocked the nation.

What do people get wrong about the history of gun control? Are there any myths you find yourself debunking?

One of the great myths is the idea that gun-control laws are an artifact of the modern era, the 20th century. Gun laws are as old as America, literally to the very early colonial beginnings of the nation. From the beginning of the late 1600s to the end of the 1800s, gun laws were everywhere, thousands of gun laws of every imaginable variety. You find virtually every state in the union enacting laws that bar people from carrying concealed weapons. That’s something people don’t realize.

When we were all colonies, there were laws in the 1600s making it illegal to discharge a weapon near a road, near buildings, populated areas or on Sundays, and that barred discharge of a gun during social occasions. In New Jersey there was a law that said you weren’t allowed to discharge a weapon when you were drunk and the two exceptions were at weddings and funerals. In the old ‘Wild West,’ they took people’s guns away when they were in a populated area, only to be retrieved when they left. That exemplifies how laws were much tougher 150 years ago than in the last 30 years.

Correction: Oct. 30, 2018

The original version of this story misstated the availability of assault weapons for civilian use by the late ’60s. At least one model was available earlier.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com