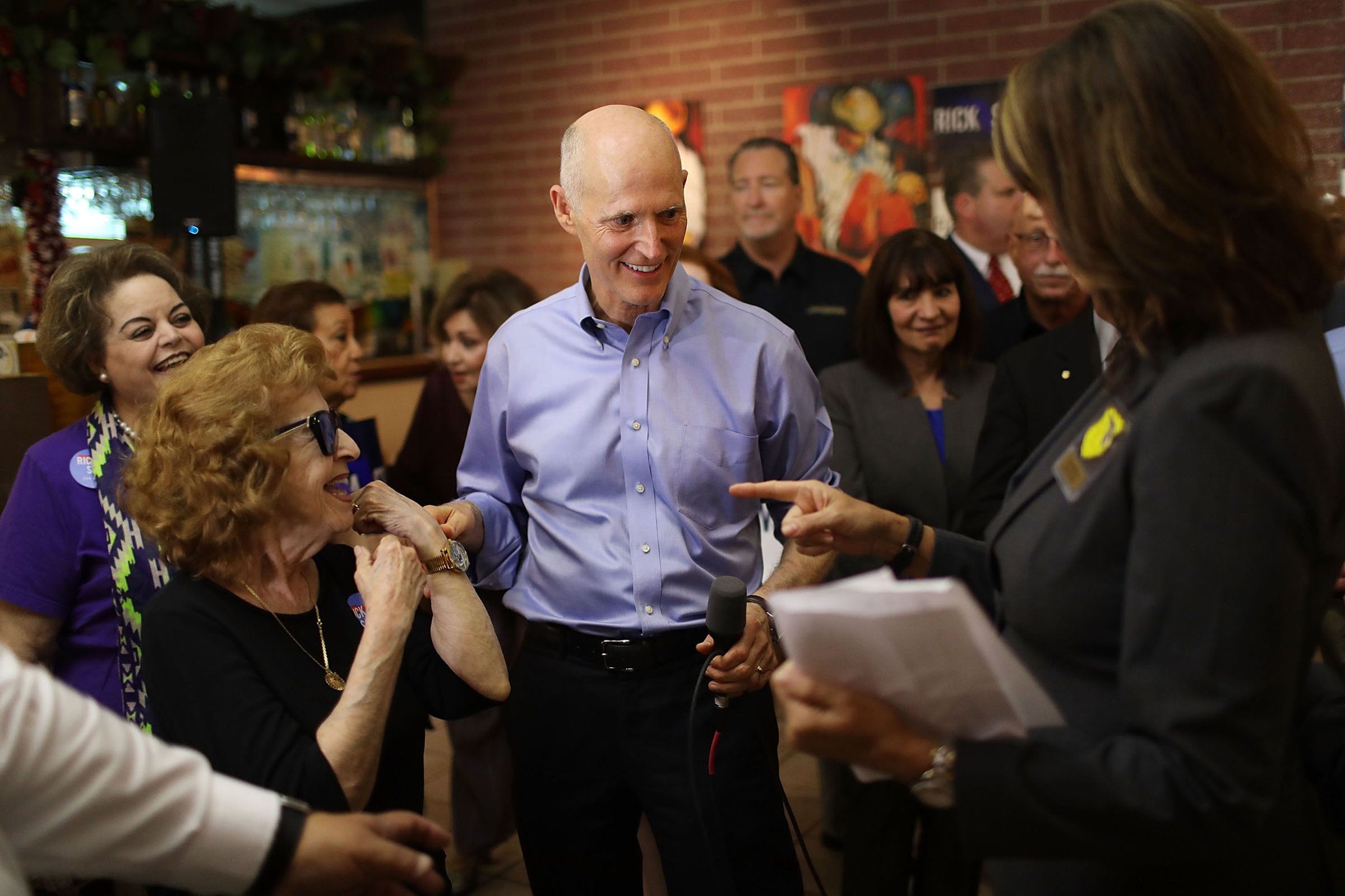

Rick Scott arrived in a sweltering warehouse on Orlando’s east side and began thanking the crowd in Spanish. “Gracias por su apoyo,” the Republican Senate hopeful told voters and employees of this flooring business founded 20 years ago by Puerto Rican immigrants. “Es mi oportunidad para conocer a mis amigos.” Thank you for your support. It’s my chance to meet my friends.

The message was clear in any language. Scott, Florida’s two-term governor, is battling Democrat Bill Nelson, a three-term incumbent, in a race that could determine control of the Senate. And both parties believe the outcome may come down to which candidate does a better job wooing Hispanic voters, who make up 25% of the state’s population and 17% of its registered voters.

If you believe national pundits, Nelson should have the advantage. Hispanic voters are routinely counted in the Democratic Party’s voting coalition, and President Donald Trump has not endeared himself to many of the nation’s 58 million Latinos by cracking down on legal and illegal immigration alike. But in a bold play, Scott is working overtime to build support among Hispanics. Two polls published in early September have put him up by double digits with the demographic group, while three in late September showed Nelson with a double-digit advantage.

While the race is up for grabs, there’s no question that Scott is outhustling Nelson in Latino communities across Florida, particularly among Puerto Rican constituents, who tend to vote Democratic. Since Hurricane Maria ravaged Puerto Rico a year ago, he has made eight trips to the island to Nelson’s three. He spearheaded a state initiative to establish welcome centers at the Orlando and Miami airports, designed to help newcomers find their footing in their new home. (When Florida International University surveyed Florida’s Puerto Ricans in a poll released in June, Scott was seen more favorably than Nelson.) The governor takes daily Spanish lessons from one of his aides, a Venezuela native and newly minted U.S. citizen. In an interview with TIME aboard his bus during a recent 10-day campaign swing, the governor touted his efforts to become bilingual. “Practicing Spanish every day is important,” he said in his second language, leaning forward in his leather captain’s chair. “Twenty percent of those voting in this state speak Spanish.” (Nelson learned Spanish in 2003 as part of an intensive State Department program.)

Scott’s language classes help explain why, in a dismal year for Republicans, he is in an effective dead heat with a well-known incumbent in the nation’s largest swing state. Moreover, his outreach to Hispanics is a snapshot of an unsung trend that could keep the Senate in Republican hands. In several other key battlegrounds, including Arizona, Nevada and maybe even Texas, Democratic candidates are at risk of underperforming with Hispanic voters, lagging behind the numbers the party notched two years ago. “There’s a lot to be angry about in terms of what this Administration is doing,” says Mayra Macias, political director of the Latino Victory Project and a former Florida Democratic Party official. “But it’s not enough to be angry. You have to give Latinos something to vote for.”

Only two years ago, it looked as if Trump would be kryptonite for GOP efforts to repair the party’s relationship with Latinos. He began his campaign for the White House by calling some immigrants “rapists”; pledged to wall off the Mexican border; and went on to collect just 29% of the Hispanic vote, according to often debated exit polls, down from the 44% George W. Bush earned in his 2004 re-election bid. Since taking office, Trump has made good on a campaign promise to crack down on immigration, called Haiti and El Salvador “sh-thole countries,” implemented a policy that separated migrant children from their parents and disputed the death toll from Hurricane Maria. Not surprisingly, a mid-September poll released by the electoral arm of the nonpartisan National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials (NALEO) found that 72% of Latino voters have an unfavorable view of Trump.

But in key states around the U.S., Republican candidates are working to overcome the Trump factor by campaigning hard in Hispanic communities. The NALEO Educational Fund poll found that 52% of Latinos who identify as Republicans nationwide have been contacted by a campaign or political group, while just 43% of Democratic Latinos said the same.

This work is evident in state polls. Hillary Clinton carried 62% of Latinos in Florida as the Democratic nominee for President in 2016; according to a Sept. 5 Quinnipiac poll, Nelson is polling at 39% among Hispanic voters. (A Sept. 25 poll from the same university, taken after Nelson started running ads, put his support among Hispanics at 61%.) In Arizona, Clinton took 61% of Latino voters; Democratic Senate nominee Kyrsten Sinema is polling at 54% among Latino voters, according to an NBC News poll released Sept. 25. In Texas, Democratic Senate candidate Beto O’Rourke is carrying 54% of Hispanics, according to a Sept. 18 Quinnipiac survey, trailing Clinton’s 2016 showing by 7 points. The comparison is inexact, since the midterm electorate is different, but the figures have left some Democrats alarmed.

Democrats have recognized the problem. Sinema is on the air with an ad in which she says in Spanish, “The Washington politicians are always fighting. Enough!” Mi Familia Vota, a left-leaning group, launched an effort on Sept. 11 to register 15,000 Spanish-speaking Nevadans, while Democrats have spent more than $12 million against Republican Senate incumbent Dean Heller. The Democratic National Committee and the state party in Florida have robust outreach efforts that include more than 50 bilingual organizers targeting Hispanic voters. Yet Republicans have been on the ground for months, even years, in these states. Consider Florida. The Republican National Committee’s “Bienvenido a Florida” programs, introduced last year, are designed to be one-stop orientations to life in Florida, especially for the roughly 200,000 Puerto Ricans who came to the state after Hurricane Maria. “We’re not delusional. The island of Puerto Rico tends to lean blue,” says Taryn Fenske, one of 19 RNC staffers stationed in Florida to help the party make inroads with Hispanic voters. Since July, the RNC has held 40 events designed to connect with Puerto Ricans, including efforts to help them register to vote, enroll in schools and find churches. They’ve also knocked on 100,000 Hispanic voters’ doors and made 65,000 calls to them. And in a state where the last two presidential elections have come down to a few votes per precinct, it can make a difference.

A few miles from the RNC offices in Orlando sits one of the state’s 14 outposts of Americans for Prosperity (AFP), the advocacy group backed by billionaire Charles Koch. In 2014, when Scott last ran for governor, the group’s political arm, AFP Action, had conversations at 350,000 doors where the person answering was likely to support Scott. Scott won by about 66,000 votes. “There’s no margin for error here,” Chris Hudson, AFP’s Florida director, told TIME in mid-September, sitting in his windowless office in a suburban strip mall. “We’re outnumbered.”

A day later, members of AFP’s Hispanic-focused project, the LIBRE Initiative, packed into a rented minivan to drive around a neighborhood near the Orlando airport, armed with a list of Spanish-speaking residents. They wanted to make sure sympathetic neighbors were aware of the election, were registered and had their questions answered. At one home, 66-year-old retiree Jose Santiago opened his door to find three women armed with tablets and a script about the importance of voting in November. After the AFP canvassers made their pitch in Spanish, Santiago told TIME that he’s leaning toward supporting Scott but hasn’t decided. The LIBRE volunteers, he added, “come around and let us know how things are going. It’s a good idea to come and see who’s going to vote, especially in the Spanish community.”

The race in Florida will hinge on hundreds of thousands of such encounters. “You don’t mount a Hispanic-outreach effort in a month,” says Andres Malave, an AFP spokesman for Florida. “For the governor, it’s been his whole eight years being actively present.”

Nelson gets the message. The Senator–who first won elected office in Florida in 1972 and has been out of government for only four years since–has never been one to run toward the television cameras. But at the urging of pals in Washington, he has done a string of Spanish-language interviews in recent weeks to talk up his service on a Puerto Rico committee, his decades of work for Florida’s Hispanic residents, and travels to Central and South America as a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Hispanics are “like all voters,” Nelson told TIME over the phone as he rushed to the Orlando airport Sept. 24 to catch a flight back to Washington. “Environment. Health care. Education. It’s all those issues that most voters care about.” Asked about his outreach to displaced Puerto Ricans, Nelson says, “I think you’re going to see a fairly big support for me in that subset of the Hispanic vote.”

Allies profess confidence but admit Nelson has work to do. Maurice Ferré, the first Puerto Rican to win Miami’s mayorship, has urged Nelson’s campaign to focus on health care, jobs and housing. Meanwhile, Democrats are gearing up to return fire after enduring millions of dollars’ worth of negative TV ads. Nelson’s “big message,” says Darren Soto, a first-term Democratic Congressman from Orlando whose father came to the U.S. mainland from Puerto Rico, “is that Scott and Trump are best buddies and Trump is anathema in our community.”

While Scott and Trump are indeed friends, the governor has distanced himself from the President on some issues. When Trump said studies on how many people died from Hurricane Maria were wrong, Scott condemned it. Days later he made his eighth trip to Puerto Rico to reinforce the point. “Do I agree with the President’s tweet? No,” Scott says, back on his campaign bus. Then, without missing a beat or taking a breath, he recognized Trump’s appeal among white residents, who still make up two-thirds of the state’s registered voters: “When I agree with him, I’ll agree with him.”

While polls show the race is tight, there’s something about Scott that seems a beat quicker. For instance, when asked why someone with his wealth and executive skills would want to go join Washington’s dysfunction, Scott has a ready answer, one that helps explain why he’s making the race for Hispanic voters so competitive.

“My mom told me that, by the grace of God, I was born in this country and grew up in this country and I got to do anything I wanted to do,” he says. “If I had been born in Cuba, I wouldn’t have this opportunity. Venezuela? Nicaragua? I was born in this country and I’ve had success, so I can do this.” It’s a sentiment tailored to the first- and second-generation immigrants who may decide the balance of power in Washington next year.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Philip Elliott/Orlando at philip.elliott@time.com