“Memory is one thing, but demanding justice is another,” says Youk Chhang.

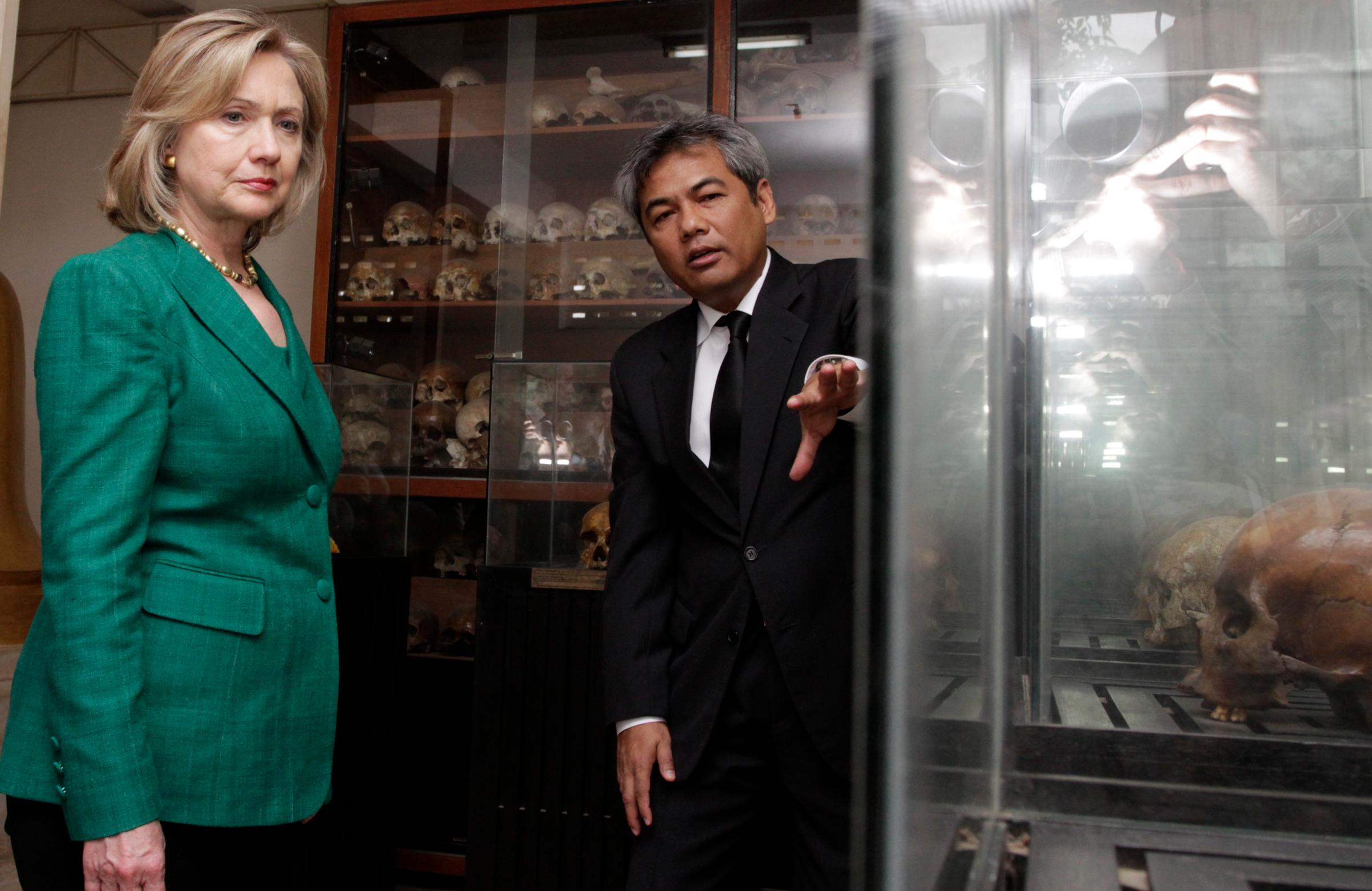

Chhang has devoted his life to balancing this tension, honoring those killed by Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge regime while holding the genocide’s perpetrators accountable.

His mission is deeply personal: as a teenager, Chhang was tortured for picking plants to feed his pregnant and starving sister, who was later killed when a soldier split open her stomach to see if she had stolen rice. She hadn’t. The regime ultimately killed a quarter of all Cambodians, about 2 million people, between 1975 and 1979. Chhang’s own life was saved by a stranger — “a hero without a name,” he says — who was killed in his place.

Now 57, Chhang is the executive director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), the country’s only genocide research center, and the keeper of Cambodia’s traumatic past. On Friday in Manila, he received the Ramon Magsaysay Award, known as “Asia’s Nobel Prize,” for his work “preserving the memory” of genocide and seeking “justice in his nation and the world.” In his acceptance speech, Chhang stressed the importance of confronting such crimes, “so that our children will not relive our mistakes.” It’s a timely call: in Myanmar, a military campaign has slaughtered thousands of Rohingya Muslims and forced 700,000 from the country; U.N. investigators recently labeled it “genocidal.”

Since its founding in 1995, DC-Cam has led scrutiny of the Khmer Rouge period: its mapping efforts have uncovered 20,000 mass graves, and the archives now hold around 1 million documents, from prison interrogations, to propaganda magazines and films, to diaries, survivor interviews, and over 30,000 biographies of victims and soldiers alike.

Read more: Youk Chhang – The 2007 TIME 100

DC-Cam’s collection has been crucial to the Khmer Rouge tribunals — where Chhang testified as a witness — and it published the first textbook to teach Cambodia’s youth about the horrors their elders endured.

But Chhang has an even greater aspiration: a museum, called the Sleuk Rith Institute, that will be DC-Cam’s permanent home and Asia’s foremost genocide studies center. But the building, designed by renowned architect Zaha Hadid to evoke Cambodia’s Angkor temples, remains on paper, and the cost, initially estimated at $2 million, has ballooned to $50 million.

Chhang will keep working, and fundraising, until his dream is realized. “If you don’t stand permanently to combat genocide, you will keep losing the battle for the rest of our life,” he told TIME by phone from his office in the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh.

How did your experience under the Khmer Rouge regime affect your work in genocide documentation at DC-Cam?

I think that it’s okay to be angry, and I held on to this anger for a long, long time. I want to take back [those] who [made] my mother suffer, who killed my family members. It’s a really physical pain.

Those things combined make me who I am now, and to work on documentation today.

Do the burdens of being the keeper of Cambodia’s memory weigh on you?

The nightmare of genocide is indescribable. It’s the worst of your imagination made reality. But my key process is prosecuting the Khmer Rouge, through the court of law, through communication, through remembrance, through learning, through any means.

I am no longer a victim: I am Youk Chhang, and I fixed my destruction. Even though [there are] scars on my legs where the Khmer Rouge tortured me, I am rebuilt.

What challenges were there to facing Cambodia’s traumatic past?

From the [1993] UNTAC election [Cambodia’s first, overseen by the U.N.], everybody came to bring peace, and to reconcile this fragile nation that has been in war and genocide for decades. But I think that on the ground, the reality was that without justice, peace wouldn’t be meaningful. So the first mission that I started wasn’t about reconciliation, it was about justice. From day one, since we started the investigation in 1995, it’s all about justice, about prosecution, about conviction. You learn that without justice, the rest will not be as meaningful.

Have you encountered adversity in pursuit of justice against former Khmer Rouge cadres?

It’s very rare. Death threats; maybe people will threaten me, but it gives me more inspiration, because I’m doing something right. If you don’t expect risks in this kind of work, then you will go nowhere, and you will remain a victim for the rest of your life.

They killed my sister, they killed my uncle, they killed all of my mother’s relatives, and they killed almost 2 million people in Cambodia. We have no other choice but to fight back.

Has Cambodia recovered psychologically from the traumas of the Khmer Rouge?

I don’t think the young generation has trauma from the Khmer Rouge. You have to look at the other side: How did people survive? How did they live? How am I now talking to you?

Humans have so much resilience. We must recognize that trauma is there as well, but it’s hidden, and recognizing things that are hidden allows us to not be enslaved by our own horrible past, and to move on.

Why is it important to have a place like the Sleuk Rith Institute in Cambodia?

We don’t have to go to the Killing Fields to remember our past. Why not a beautiful place that looks to the future?

Sleuk Rith is a place of optimism. It’s a place of learning, of remembering, of education, and it’s a new way to address the meaning of what it is for genocide to happen.

Particularly for Asia, there’s no such place for the young generation to learn from. Reaching to the past is not to live in the past, but bearing its mistakes so that we can learn from it. That’s why Sleuk Rith had to be a physical legacy. If you don’t stand permanently to combat genocide, you will keep losing this battle the rest of our life.

Read more: Asian Heroes: Youk Chhang

You have also worked on democracy promotion in Cambodia. Where do you think the country’s political future looks like?

The idea of democracy is there, but it’s a matter of someone to take the lead, and someone who has the ability to lead. We have a very young public now; we need them to vote. When you look at the public of Cambodia, its still the older generation. There has not yet been [generational] turnover.

It would be difficult for Cambodia to return to where it used to be, rather than moving on. Because of this, I have hope Cambodia will be better.

What does this award mean to you?

I’m very touched by the award, personally and for my mother. She travels with me daily; she’s now 92. And in my research, I have seen many old women, like my mother, who suffered under the Khmer Rouge.

So I wanted the award for them, for all of the mothers who raised their children with an empty hand, without shoes, without education, who rebuilt this country. I want Cambodia to recognize their roles today.

We must learn from the mistakes that we made, and this award shows that it is possible to wake up from a nightmare.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eli Meixler at eli.meixler@time.com