Damien Chazelle, director of the macho-jazz wingding Whiplash and a floaty modern musical about a great American city, La La Land, is a flashy filmmaker of great ambition. You don’t scale a movie about the first guy to walk on the moon if you’re not. Chazelle’s fourth feature, First Man tells the story of astronaut Neil Armstrong, one of the unflashiest heroes of NASA, if not of the whole last half of the 20th century. In 1969 Armstrong took the first step onto that strange, powdery surface and uttered a few simple words that captivated people all over the world. But in the years that followed, he largely retreated from publicity. In 2005, at the time James R. Hansen’s biography, First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong, was published, the former star astronaut was living quietly in a Cincinnati suburb. In 2001, while helping to conduct interviews for the official NASA oral history, professor and writer Douglas Brinkley met Armstrong and asked him if he’d ever gazed at the moon before that historic Apollo 11 flight. “No, I never did that,” he said.

Armstrong died in 2012, and it’s hard not to wonder what he’d make of Chazelle’s version of his story, adapted from Hansen’s book by screenwriter Josh Singer. This is a respectful movie, even a genuflecting one; there’s never a moment when Chazelle fails to let you know he’s doing important, valuable work. But that’s the problem: The movie feels too fussed-over for such a low-key hero. Its star, Ryan Gosling, turns in a discreet, sensitive performance, almost too sensitive for the movie around it: Minute after minute, Chazelle and cinematographer Linus Sandgren are right there with the (often) handheld camera, coming in tight for allegedly meaningful closeups or jiggling hard to connote, say, the brain-rattling feeling of being an astronaut leaving the Earth’s atmosphere in a space capsule. The wriggly camera work doesn’t make the jostling more dramatic. If anything, it makes the proceedings seem inconsequential, no-biggie events that need to be jazzed up visually with excess technique.

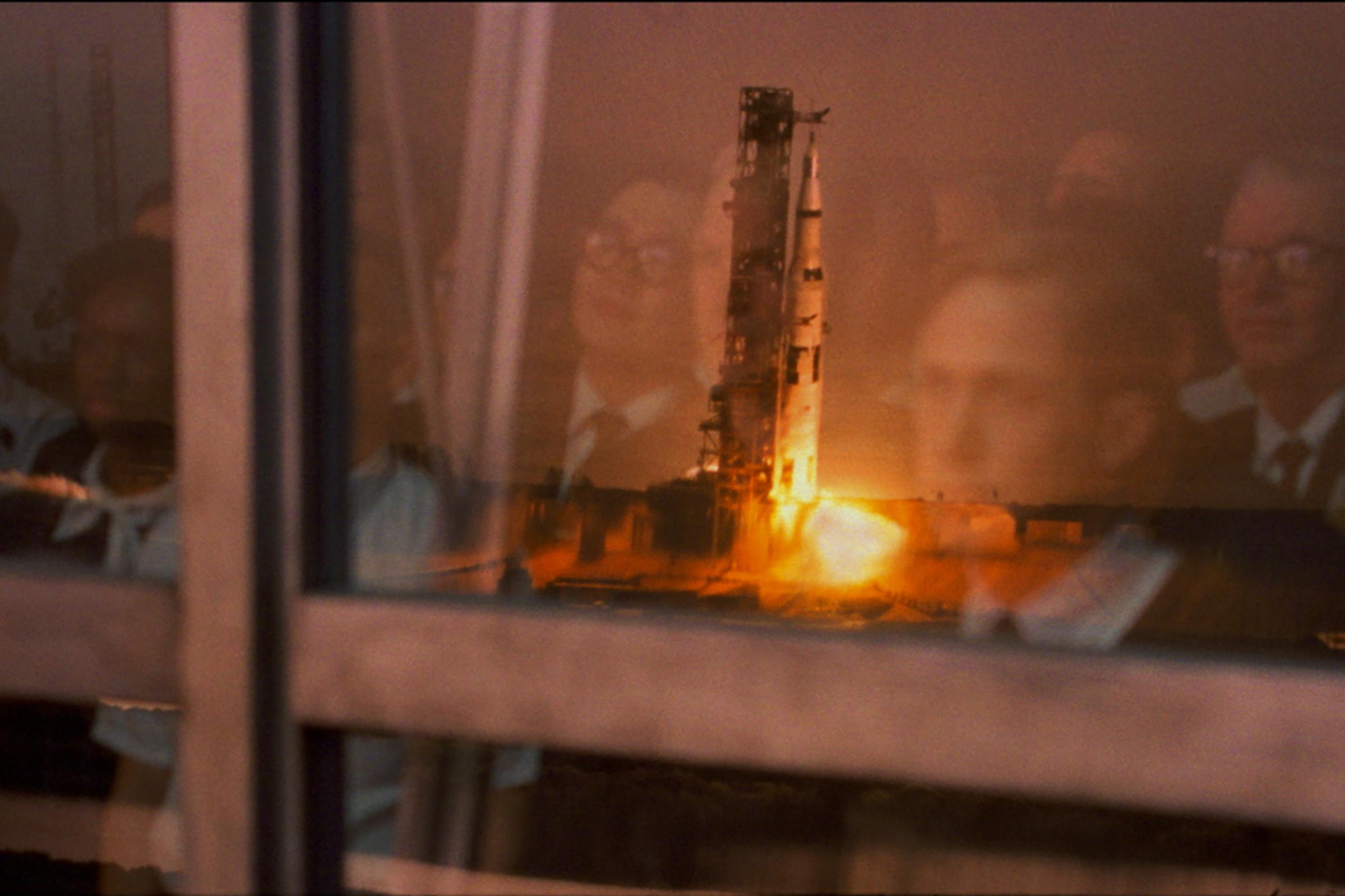

That’s a drag, because Chazelle and Singer have taken visible care with some of the movie’s dramatic details. First Man doesn’t have the jaunty spirit of Philip Kaufman’s great 1983 Tom Wolfe adaptation, The Right Stuff, which focuses on the original Mercury astronauts, the precursors to Armstrong’s group, who flew the Gemini and Apollo missions. That movie’s cheerful casualness actually enhanced the sense of danger surrounding those early missions. Chazelle chooses another path, and his instincts aren’t inherently wrong. It took a long time for the Gemini astronauts, and later those of the Apollo missions, to reach the moon, and men died trying to get there; in the movie’s best moments, Chazelle makes you feel that weight. He succeeds in making the events directly preceding that first lunar landing, a mission undertaken by Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin (Corey Stoll) and Mike Collins (Lukas Haas), seem suitably tense, even though we all know how it turned out. First Man also helps you imagine the grief Armstrong must have felt when his close friend and colleague, Ed White (Jason Clarke), was burned to death—along with Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee—during a pre-launch test for Apollo 1. Gosling is sensitive enough as an actor to understand Armstrong’s devotion to science, to the point where he must have preferred its language of numbers and facts to the murkier arena of feelings.

There’s a lot of science in First Man. You hear plenty of important-sounding men intoning stuff about vectors and coordinates and the like—a space movie needs that. But there are also a lot of feelings—too many feelings, even for those of us who like them. Chazelle and Singer seem to want to balance the greatness of Armstrong’s achievement with his own personal tragedy: He and his wife, Janet (played, with a great deal of astronaut-wife fortitude, by Claire Foy), lost their young daughter to a brain tumor in the early 1960s; shortly thereafter, Armstrong signed on to become an astronaut. Chazelle seems desperate to link these two events, as if you couldn’t make a pretty good Neil Armstrong movie without doing so. Losing a child is a devastating experience. But in First Man, Gosling’s Armstrong is tasked with reminding us of his pain in practically every other scene: As his daughter is dying, he holds her and gazes at the moon, singing a lunar-themed lullaby. After her death, he has a hallucinatory vision of her playing with some other little kids. Immediately after the funeral, he solemnly slips her little beaded bracelet into a drawer. (Keep an eye on that bracelet—it’s going to make a dramatic return.) Janet reveals to a friend that Armstrong never talks about his daughter; that’s a believable, searing detail. It’s Chazelle, with his constant stream of movie language, who can’t stop jabbering about her.

In 2018, we generally feel bad for men who can’t express their emotions, and most of us are rightly happy that more men have learned it’s OK to do so. But does it really serve men of Armstrong’s generation to have young filmmakers applying Psych 101 principles to their emotions some 60 years after the fact? Chazelle dramatizes several instances in which Armstrong’s background as an aeronautical engineer—and his overall quick thinking—helped prevent disaster, showing that there’s joy in science and exploration by themselves. But too much of First Man made me feel protective, posthumously, of Armstrong’s emotional privacy. Armstrong must have been lying when he told Brinkley he’d never gazed upon the moon—come on, we all look at it from time to time. It belongs to all of us, as a song once said. But Armstrong’s answer indicates that there were some things he just didn’t want to talk about, especially to a stranger. Life, and its loss, is its own mystery. There’s no explanation, and no cure, for the moon inside.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com