Political figures and civilians alike mourned the passing of Sen. John McCain on Saturday in their own ways. President Barack Obama released a statement noting McCain’s courage and strength; Sen. Tim Kaine reflected on what he learned from the late Senator; the White House decided on Monday to fly the flag at half-staff until his burial.

And Sen. Chuck Schumer proposed a resolution to honor McCain’s career of service by renaming a building after him. Schumer’s idea, which he announced in a tweet on Sunday, has quickly gained support from others on both sides of the aisle, from Rep. Nancy Pelosi to Sen. Jeff Flake.

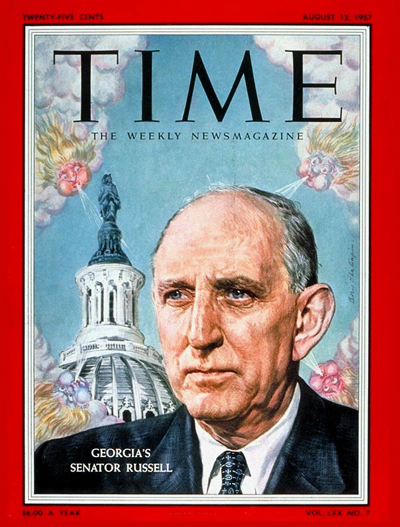

The building to which Schumer is referring is the Russell Senate Office Building, the oldest U.S. Senate office building. At present, the building is named for Senator Richard Russell, a former U.S. senator for Georgia who served for 40 years. The building also has a memorial statue of Russell, which was erected in 1995.

Schumer’s proposal is not the least bit random: McCain’s office was housed in the Russell building, and the committee he chaired, the Senate Armed Services Committee, often meets in the building as well.

But who was Richard Russell?

Richard Brevard Russell Jr. was the governor of Georgia from 1931 to 1933 and was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1932 in a special election that followed the death of Sen. William J. Harris, according to the American National Biography. A Navy veteran, Russell was nicknamed the “senator’s Senator” and “the Georgia Giant,” according to Gilbert C. Fite’s biography of Russell, for his prominence and popularity within the Senate.

Like McCain, Russell served as chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, where the Senate Historical Office says he worked toward strengthening the U.S. defense budget.

But the legislative legacy with which he is most associated is very different. Russell was a dedicated segregationist.

As the Senate Historical Office also points out about Russell, he often “used his parliamentary skills” as an adversary of the civil rights movement, opposing bills that would ban lynching and eliminate poll taxes that kept black men and women from voting despite the constitution guaranteeing them that right. A TIME cover story from 1938 reported that Russell had scoffed at “attempts to prosecute and punish lynchers”; a 1957 cover story reported on his floor speech denouncing what he saw as an attempt to “destroy the separate system for the races on which the social order of the Southern states is built.”

Russell co-authored the “Declaration of Constitutional Principles,” commonly dubbed the “Southern Manifesto,” for Congress in 1956. The Office of the Historian for the House of Representatives says that the document, signed by 101 congressmen, “urged southerners to exhaust all ‘lawful means’ to resist the ‘chaos and confusion’ that would result from school desegregation.” The manifesto was a response to 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, which made public school segregation illegal.

The culmination of Russell’s disdain for civil rights legislation came with his leading the charge of resistance to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Old Senate Office Building was named for Russell in 1972, the year after his death. Russell was chosen for the building’s rededication due to the overarching “respect for [his] legislative skills, even among his opponents,” the Senate Historical Office explains. Sen. Philip Hart, who’d later become the namesake of the Hart Senate Office Building, voted against the name decision at the time on the reasoning that it was “unwise” to guess so soon what history would think of Russell.

This isn’t the first time a proposal has come forward to strip his name from the building due to his legacy on civil rights. But Schumer’s proposal to rededicate the building in McCain’s honor will perhaps succeed where other attempts have failed, as history’s answer on Russell’s civil rights views is clear — and as politicians across the spectrum seek to hold the Senate to a standard embodied for many by John McCain himself, and the quality that Obama described as his “fidelity to something higher.”

Correction: Aug. 28

The original version of this story misstated Nancy Pelosi’s position in Congress. She is a Representative, not a Senator.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Rachel E. Greenspan at rachel.greenspan@time.com