From the vantage point of 50 years later, many of the events of the watershed year that was 1968 seem to be symbols of something broken — from the Vietnam War turning point that was the Tet Offensive, to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., to student and labor strikes in Paris to the Prague Spring.

The Democratic National Convention that August was a nominating convention for an extraordinary year, in which incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson decided not to run again and candidate Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated as his campaign was gaining steam. It was part of the larger pattern, and remains a half-century later a symbol of a broken system.

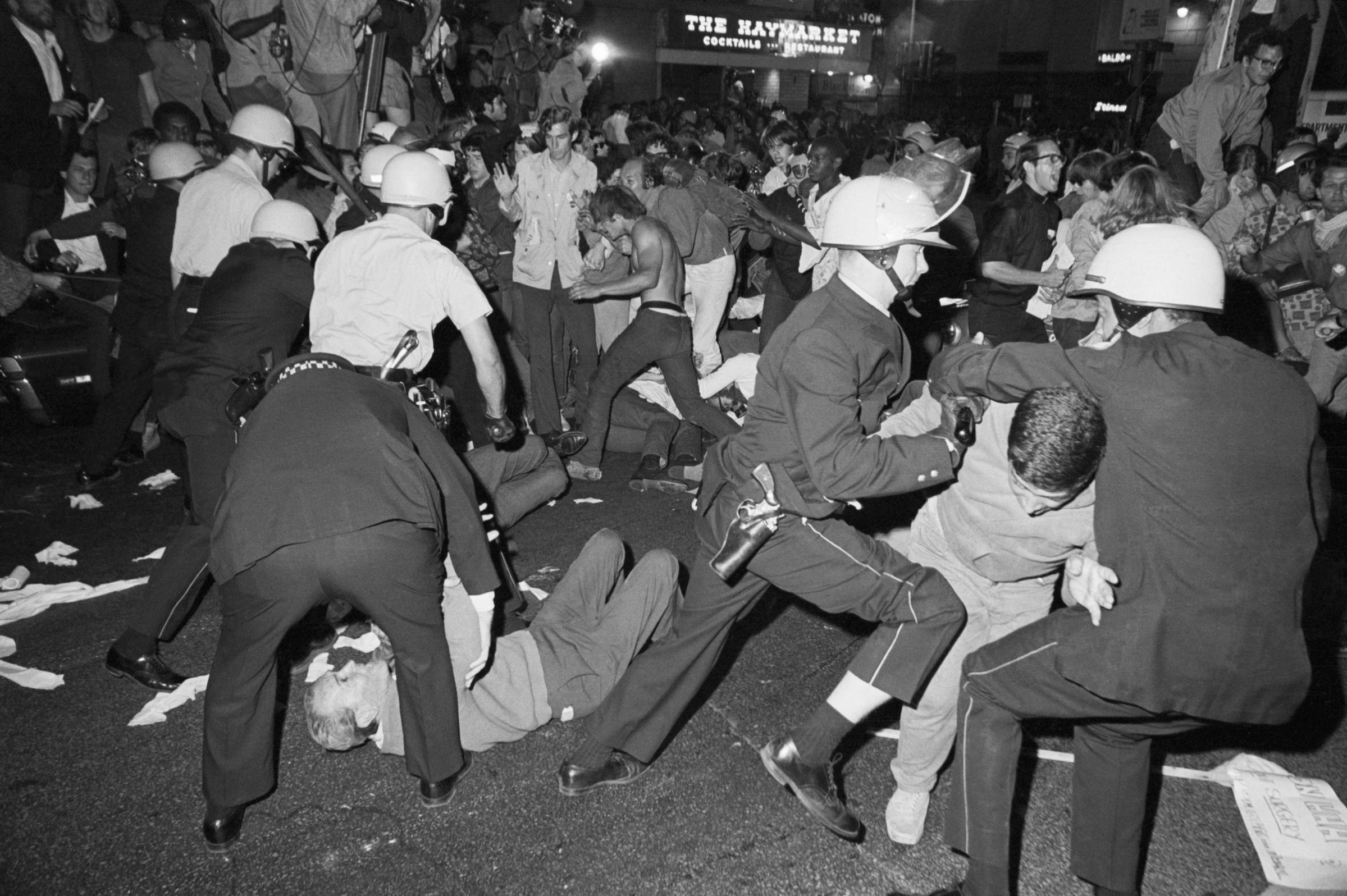

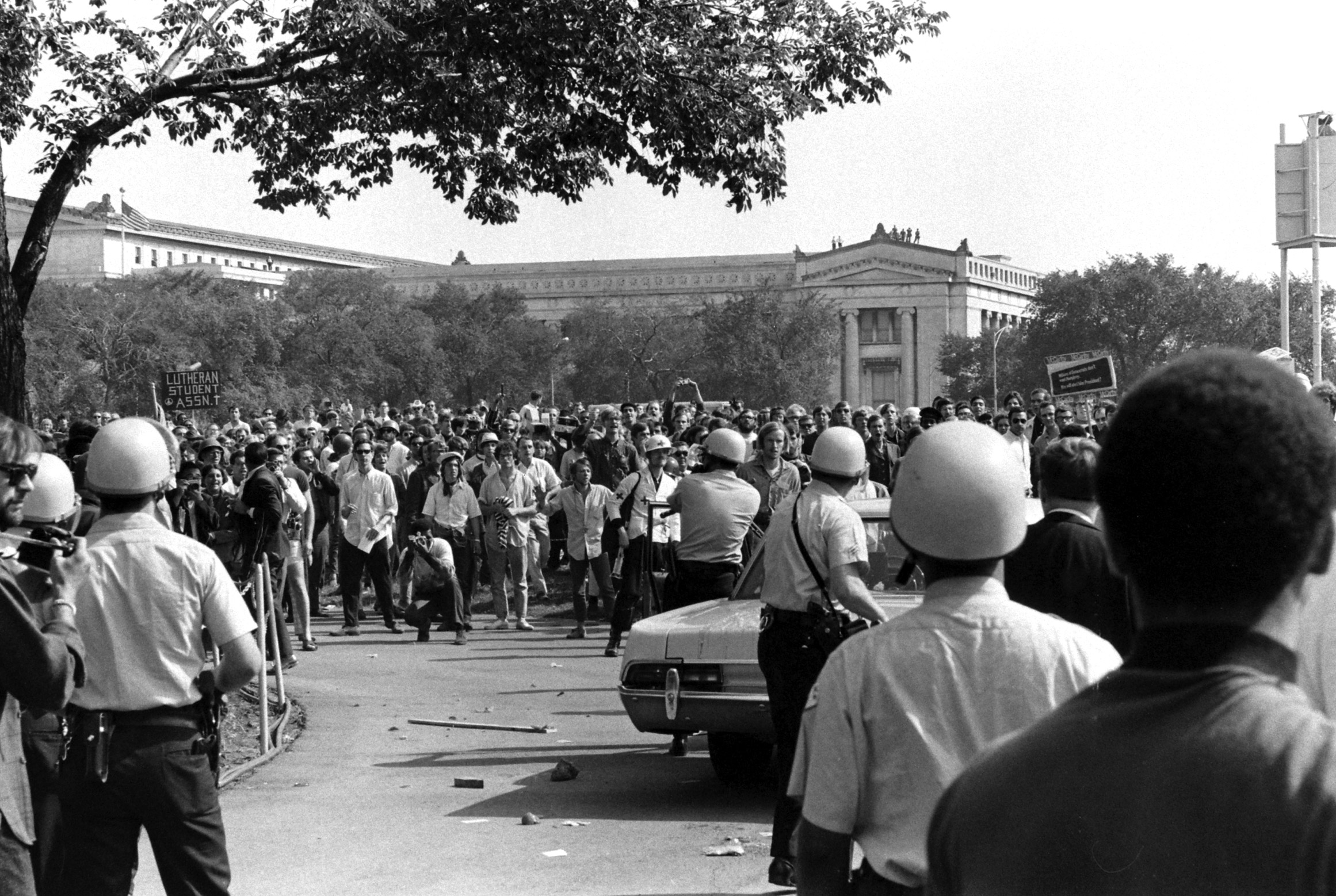

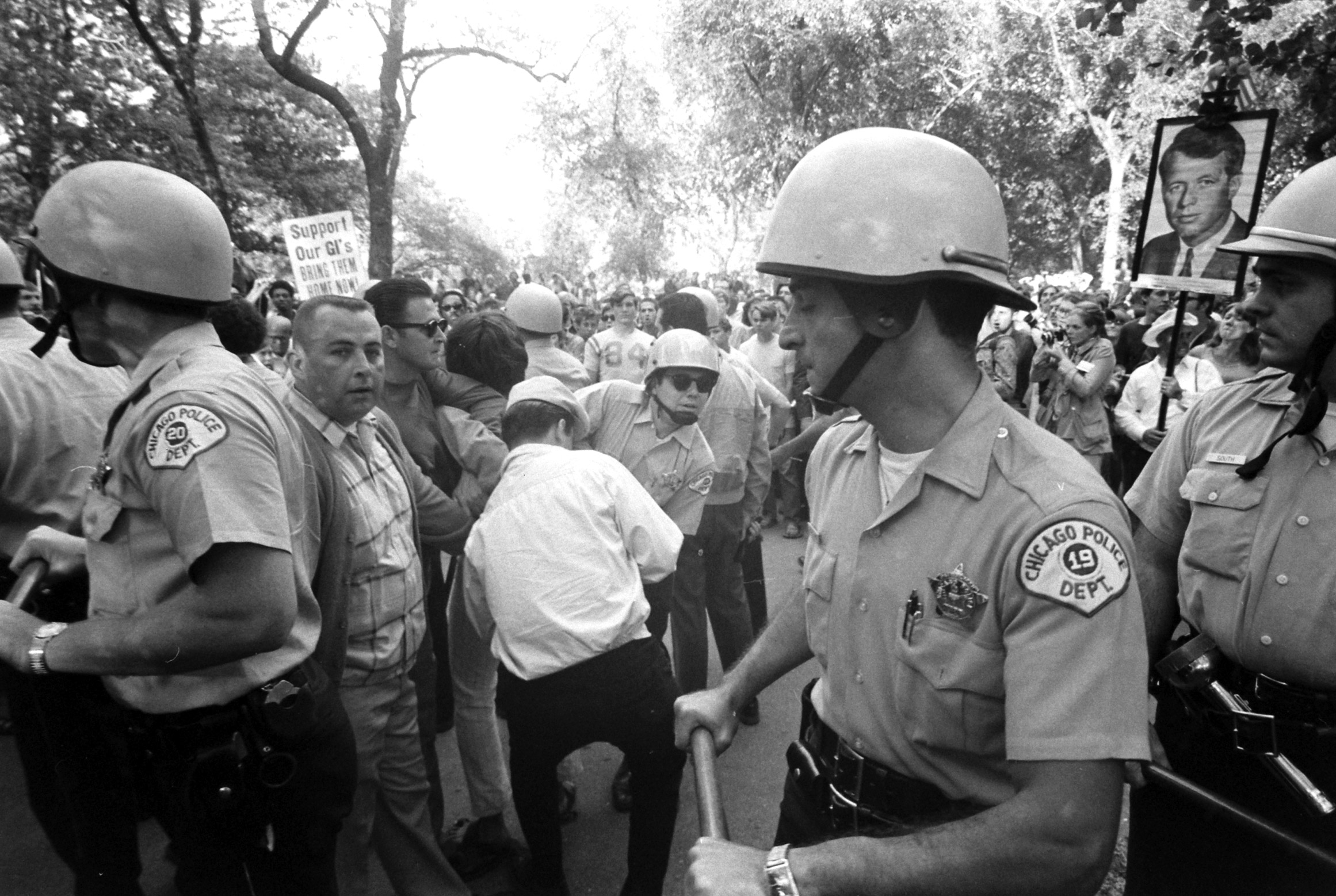

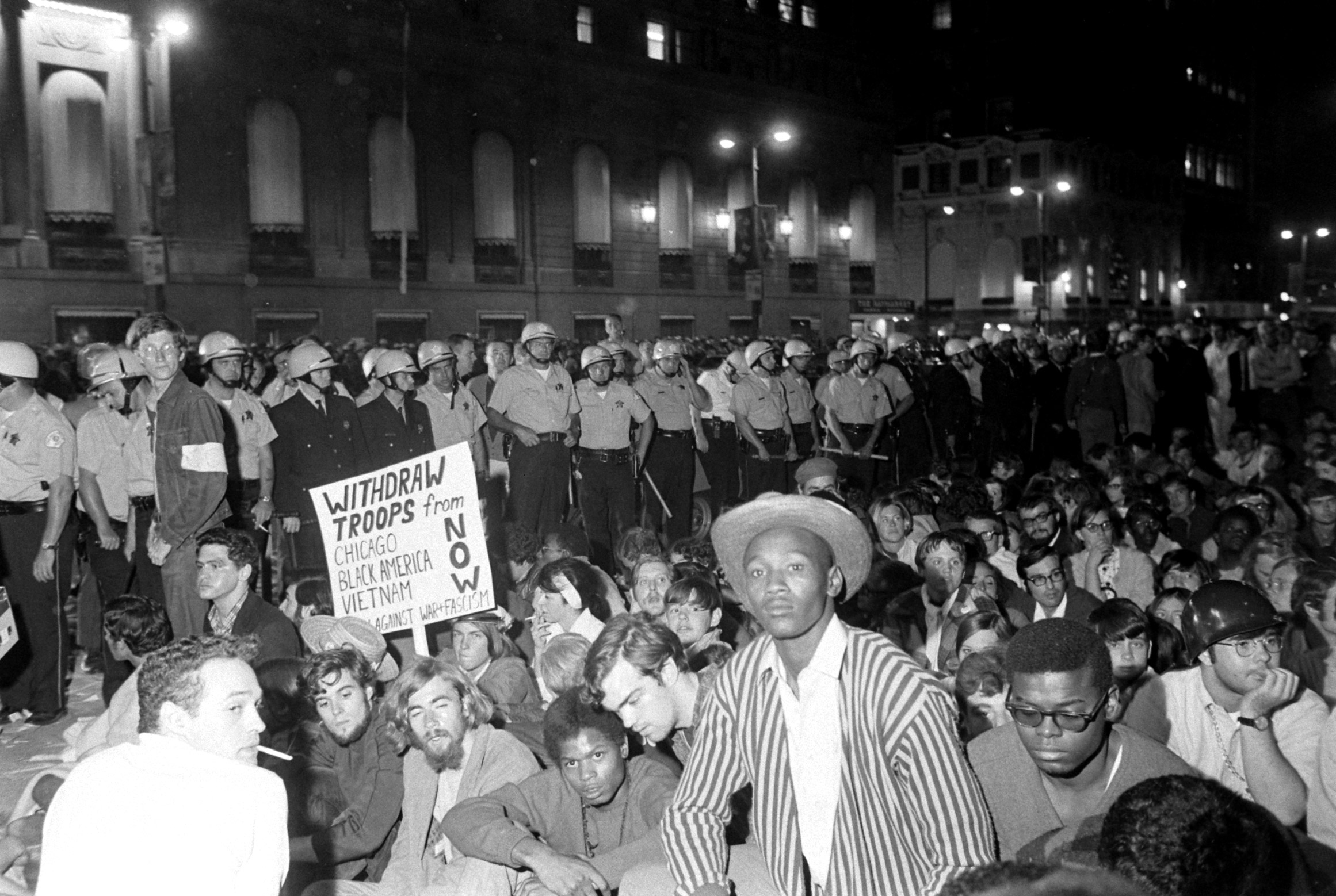

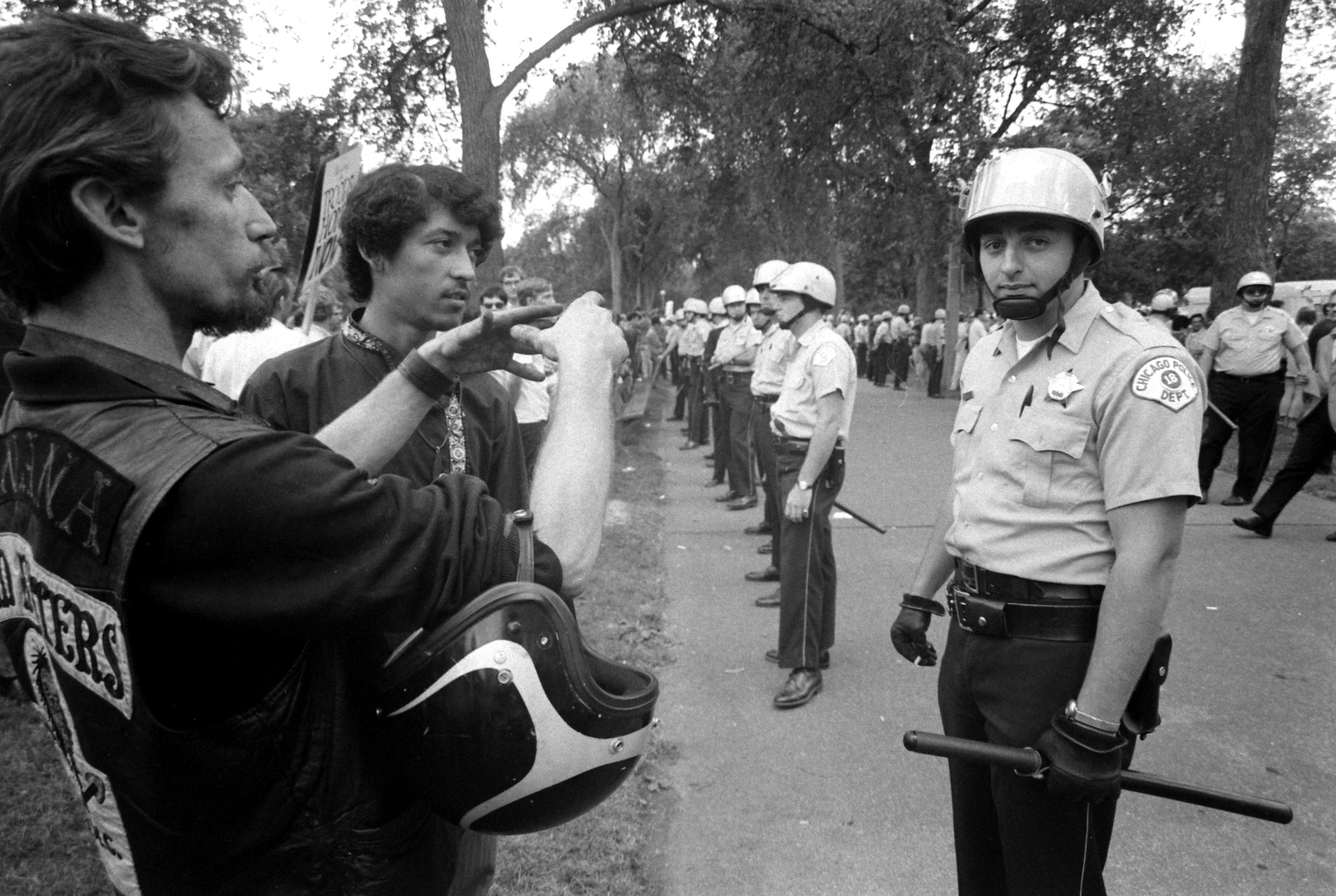

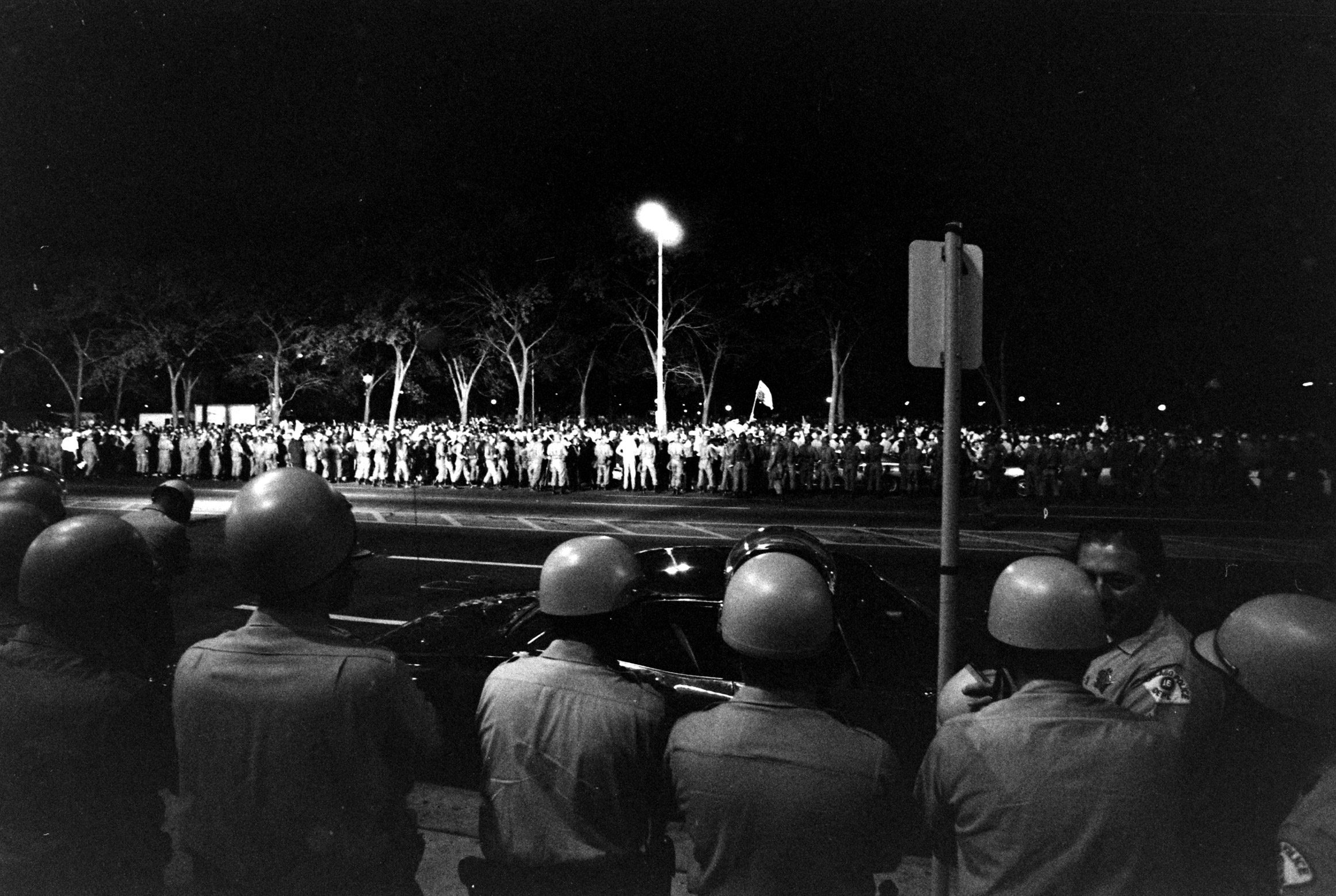

Inside the convention hall, party leaders nominated Vice-President Hubert Humphrey for the top of the ticket, even though he hadn’t run in any primary races, which would help prompt major reforms in how the Democratic Party picks its candidates. And outside, in the streets of Chicago, a massive wave of resistance — an estimated 10,000 demonstrators — drew a harsh response from city authorities, becoming a seminal moment in the history of American protest.

By the time the convention ended, 668 protesters had been arrested, and hundreds of people had been injured. The public would get to know some of those arrested better during the roughly five-year legal battle that followed. Eight participants were charged with conspiracy and crossing state lines to incite a riot: John Froines, Lee Weiner, David Dellinger, Rennie Davis, Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin and Bobby Seale.

In the walk-up to the anniversary of the most famous police-crowd confrontations of the week, those of Aug. 28, TIME spoke to several who protested about their memories of that time, the impact of the protests on the anti-war movement — and how what happened in 1968 is still playing out today.

Why They Went and What They Wanted

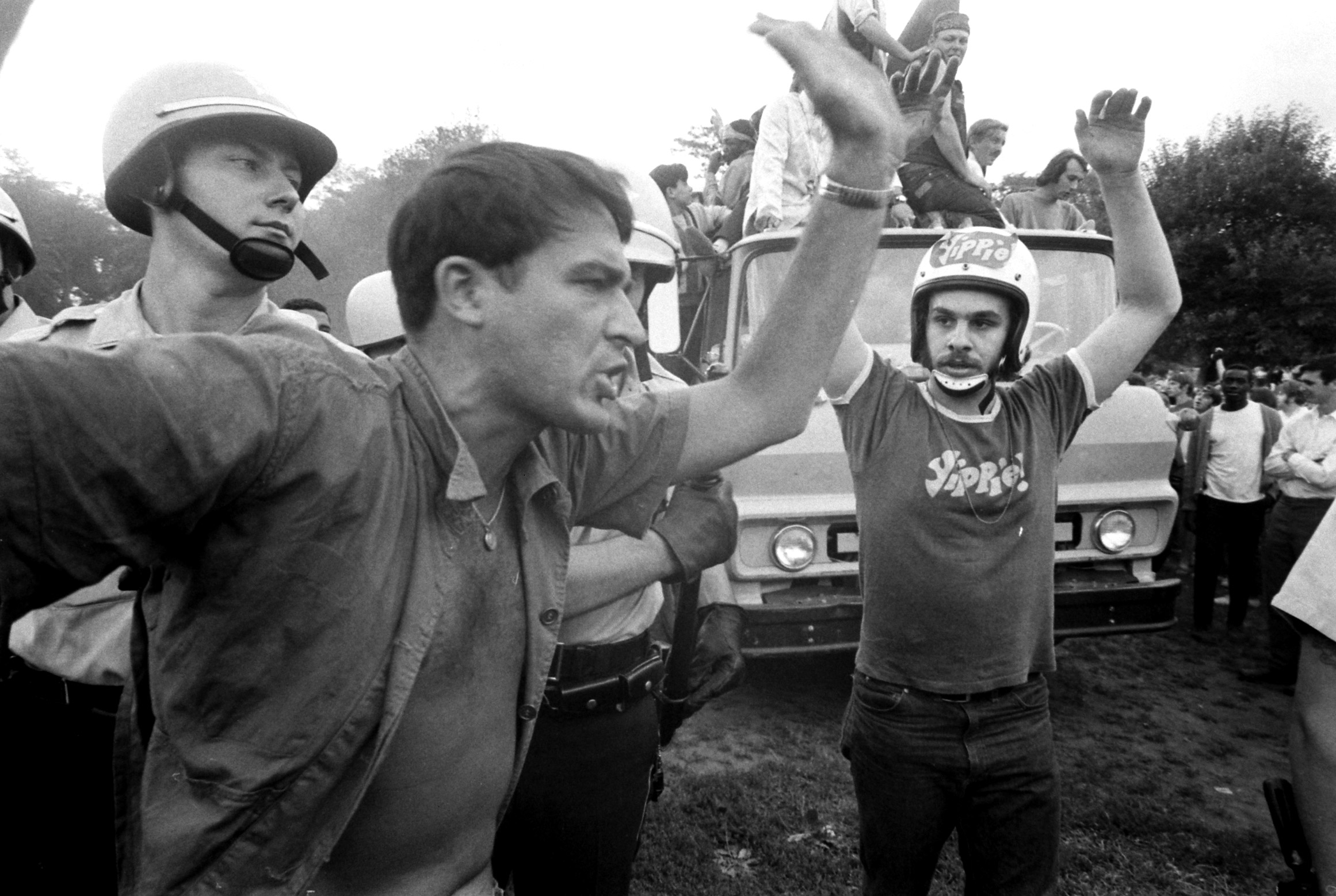

Protesters flowed to Chicago in the days before the Aug. 26 start of the convention. Some young Democrats tried to work within the system, trying to get anti-war candidate Sen. Eugene McCarthy (D-MN) nominated. Others worked the streets and the parks, believing something more revolutionary had to take place to end the War in Vietnam. And, in a commentary on the quality of candidates available, Yippies (members of the Youth International Party) “nominated” a pig for president.

Michael Kazin, then a member of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and now co-editor of Dissent magazine and professor of History at Georgetown University: I, and others in Students for a Democratic Society, went to Chicago to convince the kids in their teens and early 20s, who’d been campaigning for McCarthy, to give up their illusions about getting change within the system — break from Democratic Party and start their own party.

Judy Gumbo, then a Yippie, still an activist: We didn’t see the use of electoral politics. We hadn’t seen it do anything to end the war. Our job as we saw it was to do provocative acts of theater that would inspire others to repeat those acts wherever they were [based]. The [planning] roles were gendered; the boys went to try to negotiate for a permit, and the women were in the park making signs. The cornerstone of my experience was being in these male-dominated [planning] groups and getting up the nerve to make a point. That was a very empowering experience. To create a more integrated movement, they wanted to have someone come to speak from the Black Panther Party. I was the one who suggested Eldridge Cleaver. I had to say it about two or three times, but eventually they said that’s a good idea. He couldn’t come, but the Panther party leadership sent Bobby [Seale] instead.

Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther Party: I went because we were for human rights and against this damn war. We, the black people, shouldn’t have to be fighting this war, dying in Vietnam, if this country isn’t recognizing our civil, democratic, human rights.

Abe Peck, then-editor of alternative newspaper The Chicago Seed, now at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism: How can you organize people who would rather die than go to a meeting? You do it by spectacle. You do it by bringing a band, nominating a pig. Media coverage was our oxygen, so the claims had to get bigger and bigger to keep having coverage. I tried to warn [people]. It’s not like I was saying ‘don’t come,’ but I just wanted people to know what they were getting into, that the police were really going to try to snuff it out and you may be at risk.

Confrontations With the Police

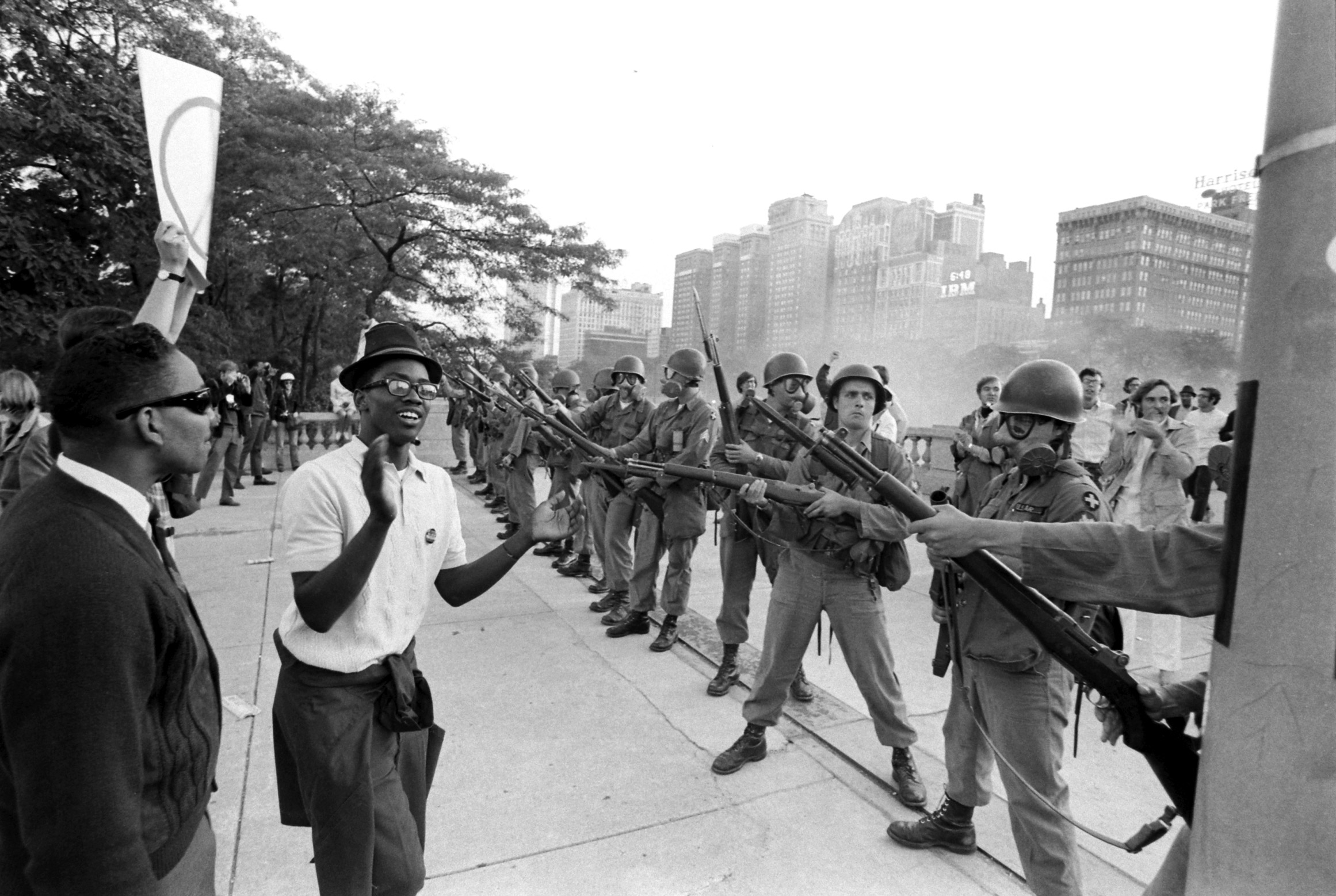

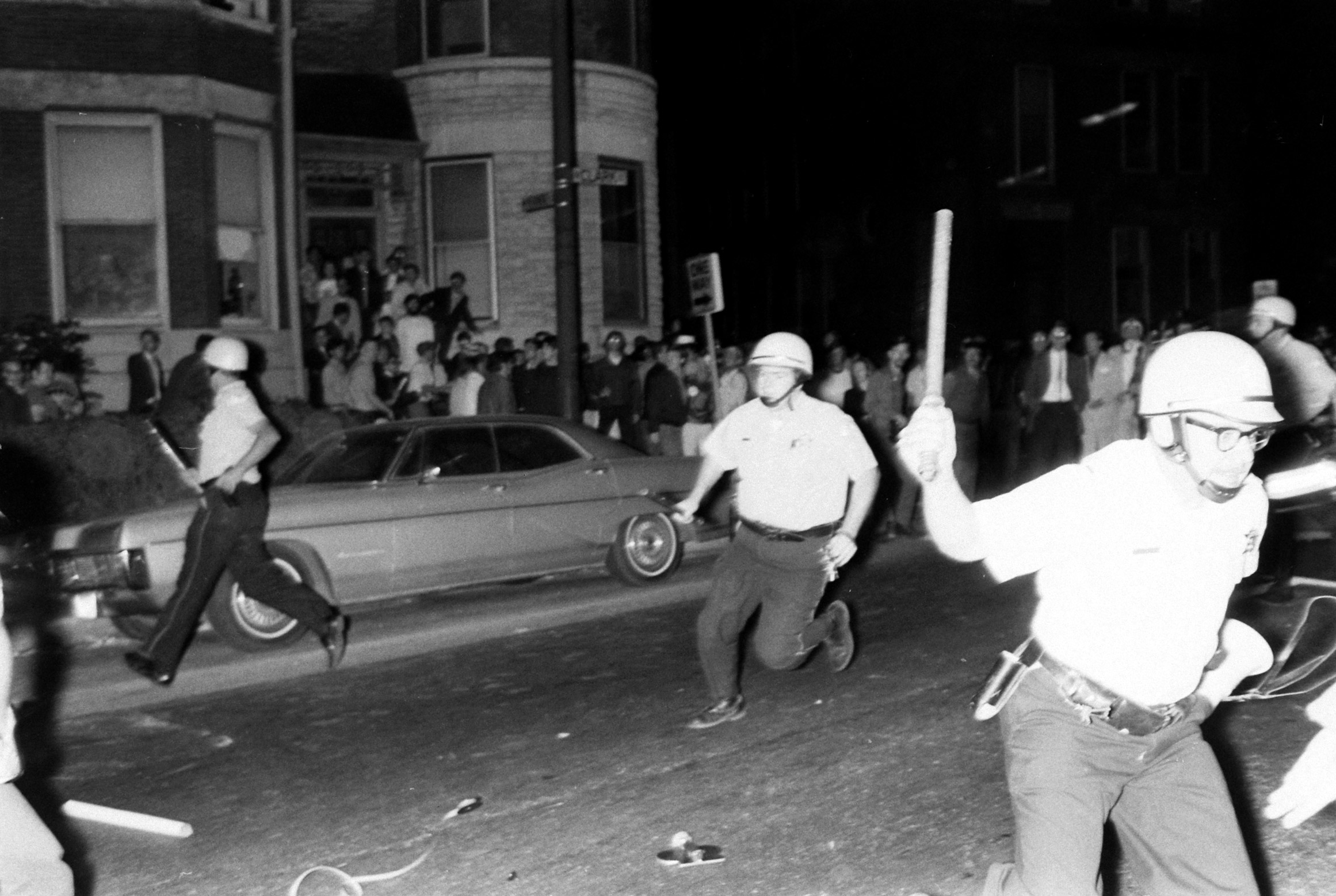

Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, who had taken an infamously harsh approach to the riots that had swept the city following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. that April, prepared for the convention by supplementing his nearly 12,000 Chicago police officers with 5,000 state National Guardsmen and 6,500 federal troops.

Peck: We’re sitting in our [newspaper] office and heard the windows crack. There were bullets in the window. A police car cruised by. We called the police, and they asked, Who do you think did that? Well, we think you did it.

Seale: In my speech in Lincoln Park, I said you’ve got a right to defend yourselves. If they come at you with a billy club, you gotta reach up and grab the billy club and try to get it out of his hand so you can swing back. [The protesters] learned Police Brutality 101. It was a course, and they all passed it with As.

Gumbo: I remember walking up and down the line of National Guardsmen outside of the Hilton with [the singer] Phil Ochs. They all had their rifles pointed at us, but one of them told Phil he had been to one of his concerts. I watched Phil stand and talk to this guy for some time, and at a certain point the guard lowered his rifle and just had a one-on-one conversation with Phil. That was the kind of interaction that we had hoped to have with the police.

Lee Weiner, a sociologist, then a Chicago community organizer, who went on to work for Americares and the Anti-Defamation League: On Aug. 28, during the huge battle on Michigan Avenue with the National Guard, I separated myself from the crowd to stand on the steps of the Art Institute and watch the crowd of people. It was the only time in my life I thought a revolution might happen in the United States.

Assessing the Impact of Protest

Hubert Humphrey officially accepted the Democratic Party’s nomination for President on Aug. 29, and the convention came to an end. Humphrey would be defeated in the general election by Richard Nixon.

Weiner: Did we accomplish what we wanted to accomplish? No, the war kept going. But I think it made the notion of resistance more legitimate.

Peck: I wouldn’t call it a success or a failure. It was just one part of this grinding process of convincing the government that the war was wrong. Obviously there were dreams we had that weren’t fully realized, and it’s probably a good thing some weren’t realized. It’s hard to build a counterculture.

Frank Joyce, then a People Against Racism member, former radio station news director and United Auto Workers union spokesperson: The outcome of the convention itself and the subsequent election definitely made me even more skeptical of electoral politics. I mean, we thought we were working in the system by expressing what we had been told were rights to free speech and protest. Could we have done the training even better, maybe coordinating more closely with SNCC [the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee] and the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference], and do more of the non-violence training that was successfully done in the South by Dr. King? With the benefit of hindsight, the answer is yes. Absolutely. We were naive. Because we grew up in predominantly white communities in the North, we didn’t have the interactions with police that black people have always had. Chicago was a wake-up call for a lot of white people.

John Froines, then a chemistry professor at the University of Oregon who had worked as a community organizer in New Haven, Conn., now professor emeritus at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health: Violence was inevitable. But the depth of the violence was far greater than we anticipated. I think the process of the war coming to the end came through a series of steps, of which Chicago was certainly the most violent.

Kazin: The famous criticism, which I think was justified, is by the late ’60s, SDS and radicals in general more identified with what they didn’t like than with what alternatives they outlined. People who were feeling like you had to increase the militancy of your demonstrations were emboldened to do that. It turned so many people, even liberals, against Humphrey and the Democrats that year. I’m not proud of the fact that we might have helped defeat Humphrey, but we might have.

The Fight That Followed

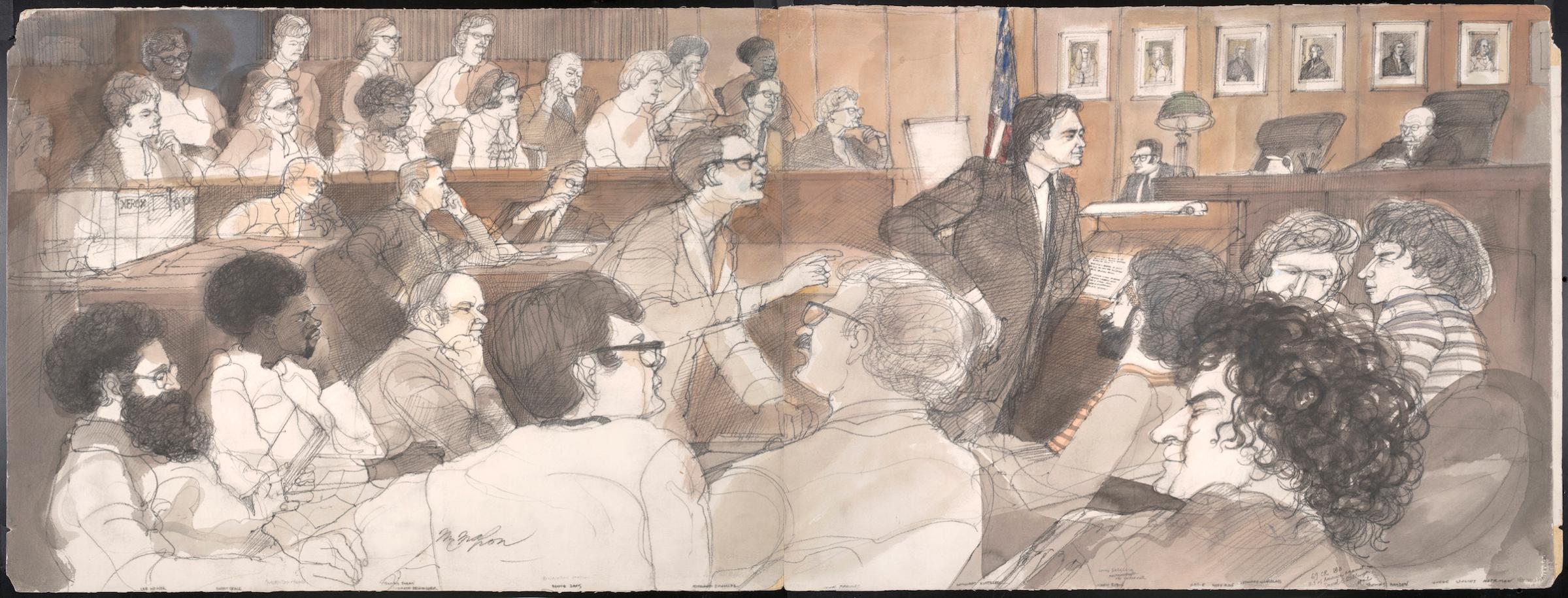

The Chicago Eight went on trial before Judge Julius Hoffman on Sept. 24, 1969, almost exactly a year after the protests. They became known as the Chicago Seven when Seale’s case was separated from the others. The remaining seven were eventually sentenced for contempt of court; five were also found guilty of crossing state lines to incite a riot.

Seale: Jerry Rubin said to be indicted here makes our protest the Academy Awards of protests. This trial was the most famous trial of all of the 1960s protest movement cases — it even overshadowed [Panther leader Huey Newton’s] trial — especially because I would not shut up in the courtroom. This judge [Julius Hoffman] denied me the right to defend myself while my lawyer was in the hospital. The other seven defendants didn’t have to be in jail the whole time, but I was in jail every day. So every time my name would be mentioned, I’d jump up and stand in my chair and cuss the judge out. I’d call him a pig and fascist. He called me a Negro. I said, I’m an African American, black American, Afro-American, but do not refer to me as a Negro. He considered that a point of contempt. They chained, shackled and gagged me for three days. Three times, three different levels of gag.

Froines: We gave hundreds of speeches on college campuses, and used the speaking fees to pay for legal costs. We’d give the speeches at night and fly back that same night to make it back to court the next day. At one point in the fall of 1969, I got a package. Everyone said don’t open it, it’s probably a bomb. It was five pounds of jelly beans. My mom sent me five pounds of jelly beans. So we had all these jelly beans to get through — and across the country, there were editorials about how the Chicago Seven isn’t taking the trial seriously because they’re eating jelly beans in the courtroom! What you really don’t realize now is how massive the media interest was in the trial. Richard Avedon took our portrait. We used the photo as Christmas cards. Then people started to take us more seriously.

Weiner: The Avedon cards we sent to anybody who’d previously given us money as a thank you, a new year’s greeting and a request for money. A friend in New York who was a photographer took photos of me and my girlfriend at the time naked with Christmas lights in our long hair, and made it into a poster that said “Make a New Year’s Revolution.” We handed it out to the young people waiting out on the cold to sit in on our trial to thank them for supporting us.

See Unpublished Protest Photos From the 1968 Democratic Convention

What 1968 Can Teach Today’s Activists

A chaotic courtroom and judicial antagonism led to the sevens’ eventual convictions — as well as Seale’s four-year prison sentence for contempt of court — to be overturned on appeal. Many who participated in that time went on to continue long careers of activism.

Joyce: I think now almost any activist or a high school student in Parkland [Fla.] starts with a sense that there’s a broader systemic problem. I think there’s broader awareness now than there was then, of the interconnectedness of social justice problems.

Gumbo: Work on any front that you can to make America the country we know it can be.

Seale: You must continue activism, and coalitions put you in a greater position. Don’t assume anything. Get people registered to vote.

Weiner: Crowd formation is quicker and easier now — perhaps one of Trump’s gifts to America. But there are still people who usually think about politics like they think about the weather. They know it affects their lives, and they don’t think people can do anything about it. In 1968, people fought against it and thought they could and should do something about it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com