How many mothers have emerged from a family trip to a Disney movie and been obliged to explain the facts of death to their sobbing young? A conservative estimate: the tens of millions, since the studio’s first animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premiered in 1937. Innocent parents might have thought that a musical cartoon version of a fairy tale would be a child’s ideal introduction to movie magic. Yet Walt Disney taught moral lessons in the most useful way: by scaring the poop out of the little ones.

As kids watched Snow White succumb to the poison apple proffered by the witch who was also her stepmother, they literally stained the seats of movie palaces with the first rush of primal anguish. Disney features, especially the early ones, were horror movies with cute critters, Greek tragedies with a hummable chorus. Forcing children to confront the loss of home, parent, friends and fondest pets, these films imposed shock therapy on four-year-olds. That psychic jolt could last a lifetime — or at least until the toddlers grew up and subjected their own children to the very same animated ordeals that they had undergone at the same age.

Those first Disney classics defined childhood as an unrelenting series of nightmares. In a backstory that suggests a palace murder spree as lurid as Hamlet Act Five, Princess Snow White (voiced by Adriana Casselotti) has been orphaned, with the dead King and Queen replaced by a stepmother (Lucille La Verne) who forces the dauphine into scullery-maid servitude. As vain as she is vindictive, the new Queen reacts to her talking mirror’s news that she is no longer “the fairest of them all” by ordering a huntsman to kill Snow White. The girl can survive only by fleeing her home and depending on the kindness of seven small strangers, for whom she cooks, cleans up and enforces cheerful discipline — becoming, in essence, the dwarfs’ doting mother.

To their young consumers, the Disney cartoon masterpieces sent mixed signals. Snow White must leave home to live; but when the puppet hero in Pinocchio (1940) goes AWOL from his creator and father-figure Gepetto, a Faginesque kidnapper named Stromboli tells the wooden boy, “When you grow too old, you will make good firewood.” In Snow White, a huntsman saves the heroine; but midway through Bambi (1942) —perhaps the most shocking moment in any Disney fable — another man with a rifle mistakes the deer’s mother for disposable game. One creature’s mother is another’s lunch.

(FIND: Bambi among the 25 all-TIME Best Horror Movies)

Indeed, among the most endangered of all Disney denizens were mothers — a fact that should have terrified the kids sitting next to their own moms in a darkened movie house. (Keep holding her hand, little one, to make sure she’s still alive.) A young boy or girl was naturally invested in the adventures of the movies’ young heroes or heroines, and would infer that their mothers were his or her mother. So what happens? Bambi’s mother dies in an act of random violence. In Dumbo (1941), the circus elephant Mrs. Jumbo is the loving single mom of her baby Jumbo Jr., who has been derisively nicknamed because of his outsize ears. When a boy at one performance cruelly pulls on Dumbo’s ears, Mrs. J. stomps forward to protect him and inadvertently causes a stampede. She is consigned to a madhouse, and her child to a life of pachyderm vagabondage in the company of a helpful mouse and some jive-talking crows.

The Disney animators’ rules on adult females: mothers are perfect but imperiled; stepmothers are wicked and occasionally homicidal; godmothers are sweet things with magical powers. Recall that the aristocratic widower father in Cinderella (1950) unwisely thought the girl needed maternal guidance and married the haughty Lady Tremaine. When the disposable dad dies, Tremaine and her gawky daughters Anastasia and Drizella treat Cinderella like a despised menial. The stepmother’s dictatorship finds its liberating equal in the Fairy Godmother’s magic. Say “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo,” and a pumpkin is transformed into a royal coach and the girl’s rags into a silver blue dress, with glass slippers to catch a Prince’s eye and heart.

(GALLERY: 13 Disney Princesses and the Actresses Who Voiced Them)

Fairy godmothers, like the Witches of Oz, can be benign or malign. In Sleeping Beauty (1959), the blessings of three kindly fairies can barely hold off the curse of the evil Maleficent (voiced by the same actress, Eleanor Audley, who had played Lady Tremaine) on the princess Briar Rose. That 1959 film was the last animated fairy tale produced by Disney before Walt’s death in 1966.

A generation later, in the animation “Renaissance” under Jeffrey Katzenberg, the studio would return to fable territory with The Little Mermaid (1989) and Beauty and the Beast (1991), both of whose heroines had fathers but no mothers. The female protagonists of two other Disney Renaissance features, the 1995 Pocahontas and the 1998 Mulan, also have to do without mothers, though Pocahontas does have a Grandmother Willow — a talking tree that croaks advice and warnings.

(READ: Corliss’s review of Beauty and the Beast)

More recent Disney animated features based on Grimm stories, The Princess and the Frog (2009) and the “Rapunzel” adaptation known as Tangled (2010), outfitted their leading ladies with a full complement of parents; Oprah Winfrey voiced the role of the frog-princess’s mom. Disney also modernized Hans Christian Andersen’s story “The Snow Queen” into the worldwide 2013 hit Frozen, a story of princess liberation that, in the grand Disney tradition, killed off both parents early on.

(SEE AND HEAR: a mashup of Frozen’s Oscar-winning “Let It Go” sung in 25 languages)

Tangled weaves the tale of a classic Disney princess — whose destiny is to come of age, triumph over adversity and, in general, woman up — with a very contemporary obsession: looking young by any means necessary. Re-enter that old reliable Disney villainess, the wicked witch. When Gothel (Donna Murphy) discovers that the 70-foot tresses of young Rapunzel (Mandy Moore) somehow bring eternal youth, or at least chic middle age, to an old crone, she swans around the kingdom while keeping her victim locked in a tower from infancy to her 18th birthday. Gothel could be many modern American parents who think that confining their teens in enforced preadolescence may make them feel younger too. Of course Gothel is a stepmother figure; Rapunzel’s real mother and father are virtuous, fretful and mostly absent.

(READ: A review of Disney’s ripping Rapunzel)

The Princess and the Frog and Tangled restored a smidge of equilibrium to the animated films of the preceding decade, when the major producers of CGI cartoons paid little attention to female characters and their offspring. DreamWorks movies (the Shrek and Madagascar series) are usually vaudeville capers. The Ice Age pictures from Fox/Blue Sky relocate the Road movies of Bob Hope and Bing Crosby into a prehistoric winterland. Universal’s Despicable Me tandem touches on parenthood, but only from the viewpoint of a single dad who would like to believe he’s a supervillain.

Pixar, which stole Disney’s hand-drawn thunder by launching the first CGI animated feature, Toy Story, in 1995, usually ignored the themes of boy-girl and mother-child in favor of stories about bonding buddies: the Toy Story, Cars and Monsters, Inc. franchises, and A Bug’s Life, Ratatouille, WALL•E and Up. Only two Pixar features so far have boasted strong mothers. In The Incredibles (2004), the superheroine Helen, aka Elastigirl (Holly Hunter), is able to raise three precocious kids while teaming with husband Bob, alias Mr. Incredible, to save the world.

(READ: A credible mom in The Incredibles)

And in 2012 Pixar finally devoted an entire feature to the mother-daughter perplex. Brave (codirected by Brenda Chapman, the studio’s first female director) took the classic Disney formula — a rebellious princess battles an imperious queen and is beset by magic spells — and gave it a beguiling twist. This time, the woman who makes the heroine’s life miserable is not her stepmother but her own mom.

In ancient Scotland, Merida (Kelly Macdonald) is a lass as wild as her curly red mane. An expert in archery, like The Hunger Games’ Katniss, Merida feels closer to the bear-hunting machismo of her father, King Fergus (Billy Connolly), than to the civilizing demands of her mother Elinor (Emma Thompson). She’s both a tomboy and a sullen teen who responds to her mother’s every request by whining, in two harsh syllables, “Mah-ahm!” When urged to choose a suitable beau for a husband, Merida screams, “I hope you die!” at the woman who gave her life. The Queen doesn’t die, but she is transformed into a bear — part regal Elinor, part huge, clumsy creature.

(READ: Corliss’s review of Brave)

Kids have often thought of their parents as monsters, and when Brave turns into My Mother the Bear, it taps both maternal helplessness and the love a child feels for any wounded creature. In this Beauty and the Beast, the sympathetic beast is a mom. Now isn’t that beautiful?

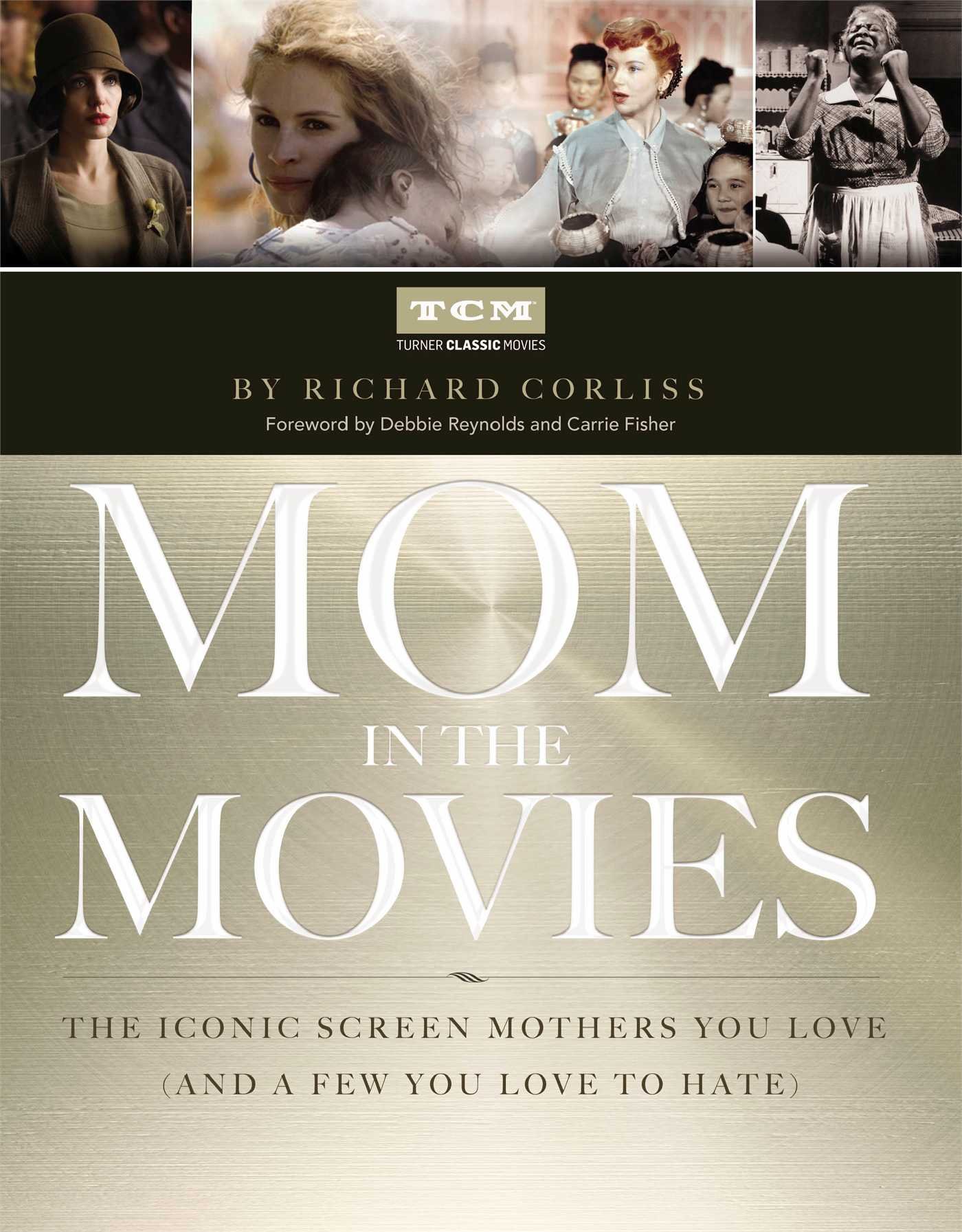

Richard Corliss’ book Mom in the Movies: The Iconic Screen Mothers You Love (And a Few You Love to Hate), published by Simon & Schuster, is out now.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com