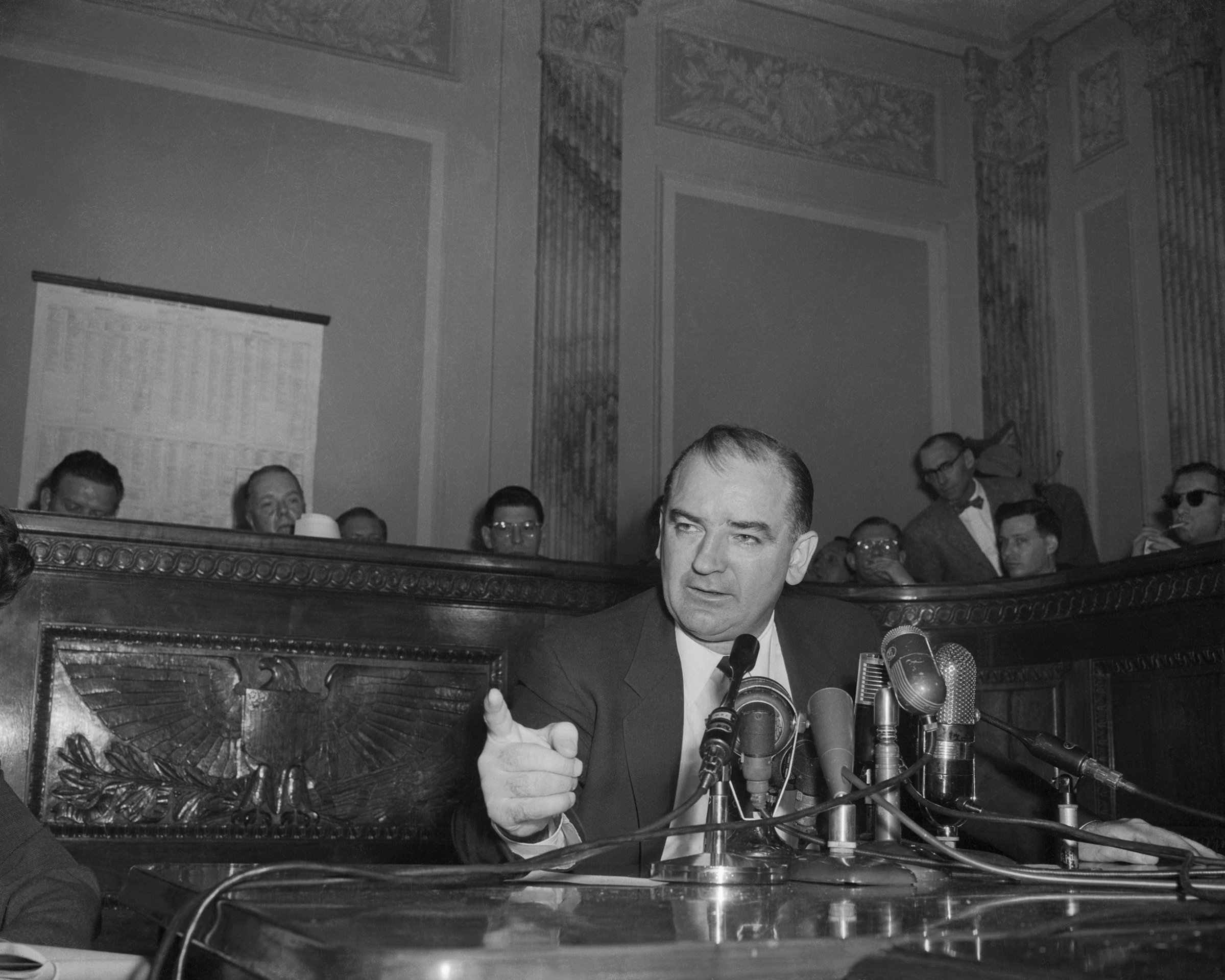

The Evening ended badly. on Dec. 13, 1950, the Washington columnist Drew Pearson was being feted at a birthday dinner at the Sulgrave Club near Dupont Circle. A vocal opponent of Senator Joseph McCarthy, Pearson had relentlessly attacked the Wisconsin lawmaker ever since McCarthy launched his red-hunting campaign that February. Still, small-town Washington being small-town Washington, McCarthy was invited to the party. He was, one notable guest recalled, spoiling for a fight. Emboldened by shots of bourbon, McCarthy asked Pearson to step outside, but the columnist demurred.

At the end of the party, Senator Richard Nixon–the guest who noted McCarthy’s belligerence–walked into the club’s cloakroom to find McCarthy’s “big, thick hands around Pearson’s neck,” Nixon remembered in his memoirs. The Senator had kneed the columnist twice in the groin, and in front of Nixon he “slapped Pearson so hard that his head snapped back.” McCarthy grumbled, “That one was for you, Dick.” Nixon tried to play peacemaker, stepping between the two men. Pearson hurried away, and McCarthy strutted a bit, remarking, “You shouldn’t have stopped me, Dick.”

A street fight in the cloakroom of the Sulgrave may seem like a relic from a different era, but the scene is actually a perfect image for the Age of Trump. A headline-hunting demagogue is once again lashing out at the press, and both McCarthy and Nixon have been vaulted back to the fore of the national consciousness.

The 45th President, to put it charitably, is hardly a student of history, so his forays into the American past tend to repay attention for whatever light they may shed on the curious chambers of his mind. A showman who prefers to act on instinct rather than cool consideration, he has nevertheless in recent days turned backward in search of aid in the battles of the present, invoking both McCarthy and Nixon as he struggles to discredit special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation amid the conviction of his former adviser Paul Manafort and the guilty plea of his former personal lawyer Michael Cohen.

That Trump has mused about McCarthy and Nixon is revealing, for the analogies draw on two politicians whose public careers ended in disgrace and defeat: in McCarthy’s case, censure by the Senate; in Nixon’s, resignation from office. It’s as if the President identifies with these dark figures and may well see his own predicament in similarly existential terms as he awaits Mueller’s report and the final outcomes of Manafort’s and Cohen’s legal travails. As Mueller has closed in, Trump has not tweeted about Iran-contra, for example, or Whitewater–crises that other Presidents survived.

In a moment that stretched the boundaries of irony beyond recognition, the President took to Twitter to accuse Mueller of McCarthyite tactics, itself a McCarthyite maneuver. Yet Mueller is not the McCarthyite figure; Trump is. Both McCarthy and Trump were opportunists who used whatever issue might be at hand to dominate the news and seek power. McCarthy turned to anti-communism, his lawyer Roy Cohn said, the way other people might buy a car: as a means to an end. For McCarthy, the end goal was fame and influence. Trump embraced the disproved conspiracy theory that Barack Obama was not born in the U.S. to launch his foray into right-wing politics, eventually gaining enough of a foothold to seek the presidency in 2016. (And then there’s the Cohn connection: McCarthy’s lawyer also represented Trump in New York’s real estate wars and served as a key mentor.)

Both McCarthy and Trump understood the media of their day, manipulating it while simultaneously attacking it as corrupt and biased. And both had little regard for the truth. “He was impatient, overly aggressive, overly dramatic,” Cohn recalled of McCarthy in 1968. “He acted on impulse.”

Trump’s tweet about Mueller was followed by one returning to the minutiae of Watergate. In an assault on a New York Times report about White House counsel Donald McGahn’s cooperation with Mueller, the President wrote that McGahn was not “a John Dean type ‘RAT'”–an allusion to the 1973 testimony of the Nixon White House counsel that helped reveal the cover-up of the Watergate burglary. The President’s own parallel between the two events shows that he has now evidently begun to see the Russia investigation as something akin to Watergate, a scandal that cost the President his job.

Analogies, of course, are frequently imperfect. Most of the time examples from the past are useful not because they neatly predict the future but because they can create a sense of proportion and perspective about the present. Yet as the historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. used to say, history is to a nation as memory is to a person, and all of us tend to judge the moment in reference to what’s come before. That Trump is alluding to the falls of two flawed leaders suggests that he may, at least subconsciously, be thinking about his own.

This appears in the September 03, 2018 issue of TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com