Everyone wants a piece of the President of the United States. But some people take that idea literally.

Long before camera phones made it possible to quickly snap a memento of a person, before the invention of photography even, collectors were snipping hair to keep as reminders of their friends and loved ones. The same was true for the Commander-in-Chief.

One example of that concept hits the auction block this weekend: 25 strands of hair believed to have come from Abraham Lincoln.

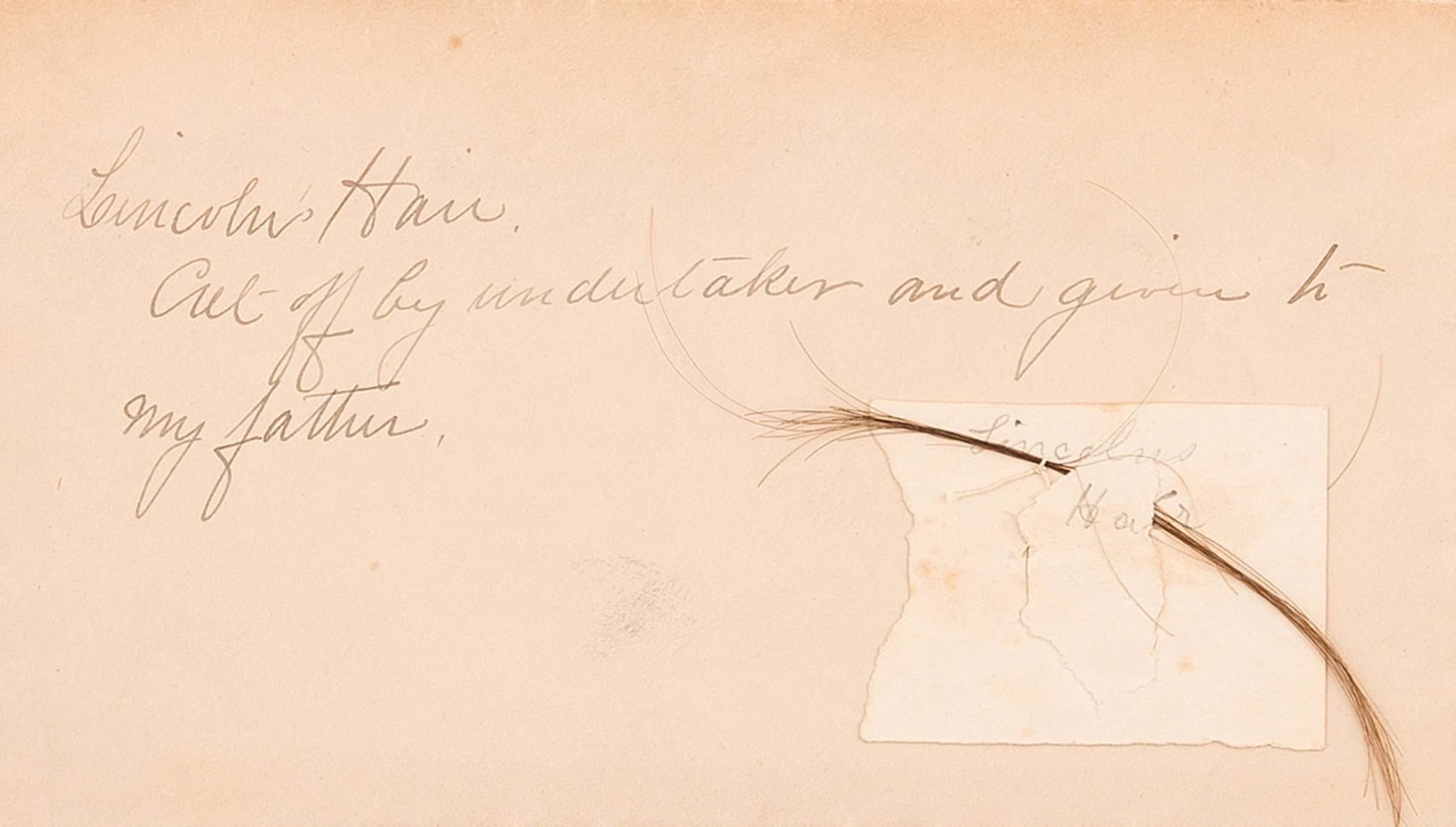

The roughly three-inch-long strands of hair are thought to come from the private collection of the famous Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner, who may have received it from Lincoln’s undertaker after the April 14, 1865, assassination of the President at Ford’s Theatre. That backstory comes down to modern times via a note believed to have been inscribed by one of Gardner‘s children on the envelope in which the hair was found — it reads, straightforwardly, “Lincoln’s Hair: Cut off by undertaker and given to my father” — and is supported by a 1926 letter from a noted collector of Lincoln memorabilia. The woman who came across that envelope had no idea it in her family until she stumbled upon it while cleaning out the Texas home of her late mother; she thinks her mother’s ancestor, a judge in Washington, D.C., may have acquired it somewhere down the line.

The strands are expected to fetch about $15,000, according to Heritage Auctions. Past sales of Lincoln hair included a lock that had been cut off by Lincoln’s Surgeon General of the U.S. Army Joseph K. Barnes (for $25,000) and one in a locket that belonged to the daughter-in-law of Simon Cameron, Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of War (which went for nearly $40,000).

“Following Lincoln’s death, there’s a rush to find mementos of anything that Lincoln touched or gave that was personal,” says Harry R. Rubenstein, former curator of political history at the National Museum of American History and expert on Lincolniana. After the assassination, “the military stepped in to guard Ford’s Theatre as a crime scene because people were trying to get mementos.”

And Lincoln isn’t alone. For as long as there have been American presidents, people have wanted their hair.

Even before George Washington was elected, he was getting hit up. Samples of his hair are scattered nationwide. Some came directly from his Philadelphia barber in the 1780s, Martin Pierie, others from his secretary and aide Tobias Lear, who was tasked with “distributing presidential relics to friends and admirers” after the first American President’s death. Lear described cutting off a chunk of the former Revolutionary War General’s hair in an account of the burial, according to Robert McCracken Peck, curator and keeper of the collection of hair at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia. A March 18, 1778, letter indicates that Washington himself sent some of his hair from his camp at Valley Forge to the daughter of the New Jersey Governor William Livingston when she requested some. There are accounts of Martha Washington wearing a locket of her husband’s hair, and even cutting off a piece directly from his head when the wife of one of his officers asked for it after the inauguration of his successor John Adams.

The reasons why people collected — and still collect — presidential hair are varied, though the personal motivations for any given collector can be a bit of a head-scratcher.

Lockets with presidential hair could be seen as status symbols. As immigration increased in the United States, the nation’s changing population encouraged some families who could trace their ancestry back to Washington’s inner circle — or similar access to Revolutionary-era power — to boast that they were here first, Peck argues, and one way to do that was to display presidential hair in jewelry designed for that purpose. Nostalgia also drove hair collecting, which was popular during the economic recessions of the mid-19th century as well as during the Civil War, as people sought to preserve reminders of a rosier past. During the Civil War in particular, soldiers and wives carried lockets of each other’s hair as reminders of home and their love; when tragedy struck, those lockets were worn as mourning jewelry.

The practice of collecting hair was also part of a larger concept about proper ways to mark special events and people. Much more so than is the case in the U.S. today, in previous centuries it was normal to want to take home a physical piece of an experience.

“If you went to Mount Vernon when Washington was alive, you were almost obligated to take out a pen knife and get a piece of it,” says Larry Bird, a retired curator at the National Museum of American History who’s written about its collection of presidential hair. “You had people taking an acorn from [a historic person’s] grave or traveling around the country shooting columns at capitals and taking little bits and pieces home. That was the way you saved the past. Today you might describe it as vandalism, but at that time, there wasn’t the idea that you’d preserve a whole estate. That didn’t occur to people until the eve of the Civil War.”

The National Museum of American History’s collection has a wooden display of hair of presidents from George Washington to Franklin Pierce, which was collected by John Varden in the 1850s. Though he put out a call for submissions —“Those having hair of Distinguished Persons, will confere [sic] a Favor by adding to this Collection” — his reasons for collecting the hair haven’t been found in any of his writings, according to Bird, who wrote about it in Souvenir Nation: Relics, Keepsakes and Curios from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Philadelphia lawyer and amateur naturalist Peter A. Browne, who died shortly before the Civil War, built his collection of hair from 13 of the first 14 presidents (except Millard Fillmore) by writing letters directly to presidents or people who knew them. For example, in the case of Andrew Jackson, the President’s son replied that his father would do it if he hadn’t just gotten a haircut; he later sent Browne a when the hair had grown back enough. (Peck used Browne’s method to obtain the most recent presidential sample from Jimmy Carter, the only hair from a living president in the Drexel collection.)

Browne’s presidential hair was part of a larger collection of human and animal hair — that classified strands as cylindrical, oval, and “eccentrically elliptical” — which suggests that perhaps he had scientific and philanthropic goals in mind. Browne’s enthusiasm came during a period when people were studying phrenology, the pseudoscientific idea — which also played a role in scientific racism of the period — that the shape of people’s heads can tell you something about them, and perhaps he had a similar idea about what could be read from hair. “He asked people traveling around world to send him samples of hair from people that they met and tried to collect hair from as many different kinds of people, and celebrities became a part of that, because he thought could he determine by looking at the hair a criminal from a President of the United States,” Peck tells TIME.

One of the collectors who is still active is John Reznikoff, founder and President of University Archives in Westport, Conn. In the early ’90s, he acquired a collection of presidential hair that had belonged to Margaretta Pierrepont, the wife of Edwards Pierrepont, President Ulysses S. Grant’s Attorney General, from Robert White, a cleaning-supply salesman (who collected Kennedy memorabilia and shrunken heads). In addition to hair from 19th century presidents — including a lock of Lincoln hair that a Civil War general is thought to have purchased from the son of the President’s surgeon Charles Sabin Taft, which Reznikoff thinks could be worth as much as $500,000 today — his collection boasts hair from 20th century presidents Eisenhower, Nixon, Reagan. Items from his presidential hair collection have even been used to help solve a mystery, when a piece of John F. Kennedy’s hair was tested to help debunk a claim from a man who said he was the President’s son.

But Reznikoff — who also has hair from other historical figures, such as Napoleon, Charles I, Albert Einstein, Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe — wants his collection to be useful for more than just confirming who’s related to whom. He admits to having “Jurassic Park mentality” about future uses of his collection.

“Once the DNA technology advances further, is there a point when you’ll be able to take DNA from hair and clone an individual?” he ponders. “And will my collection be the basis of a cocktail party of all the greatest people in history?”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com