Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul and first woman to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, died on Thursday. She was 76.

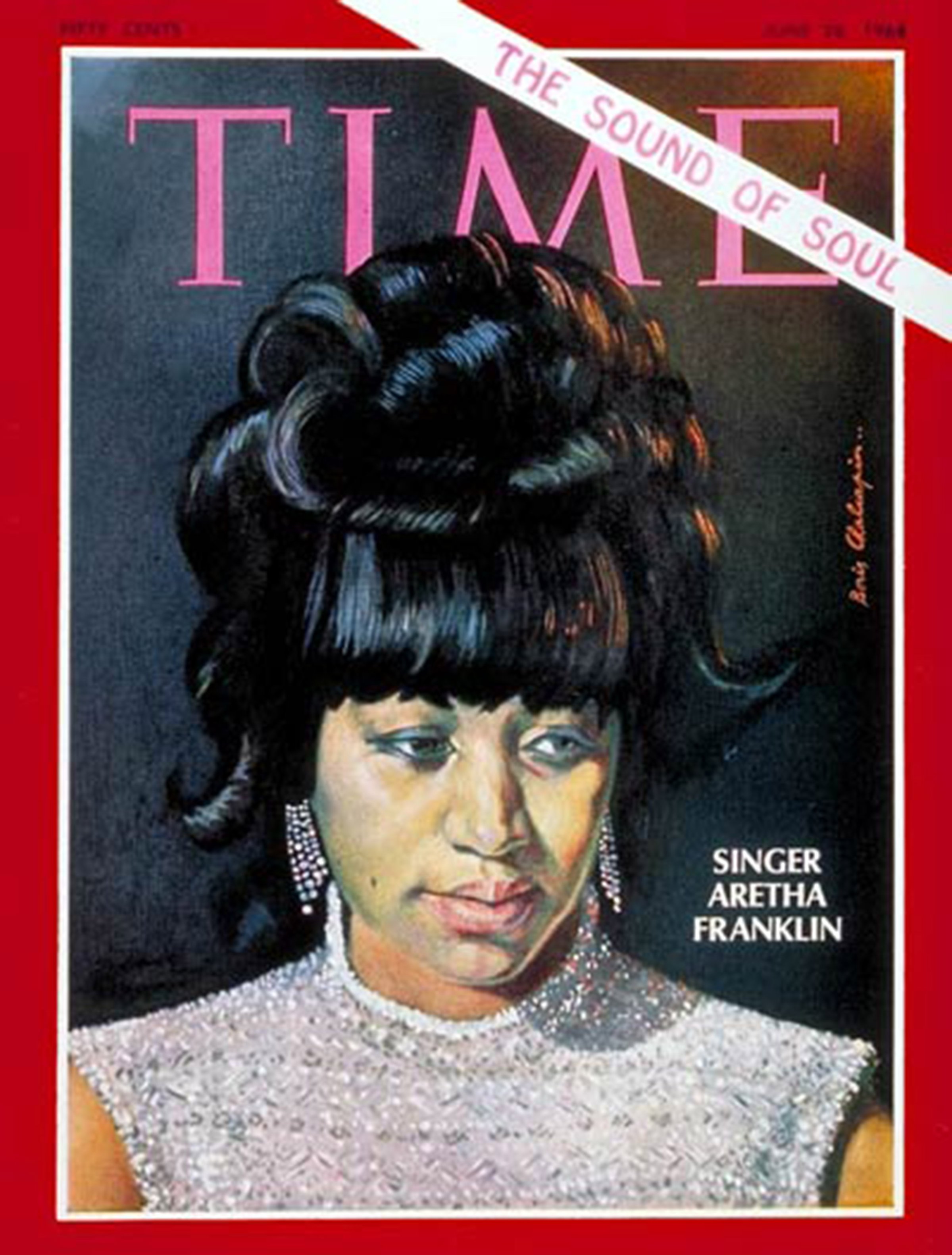

It’s been 50 years since TIME billed the 18-time Grammy winner as “The Sound of Soul” on the cover of the June 28, 1968, issue, when her album Aretha Now had just come out, her second that year. The main article’s headline “Lady Soul: Singing It Like It Is” was a riff on the album that had come out that January. And as TIME’s story detailed, Franklin’s music channeled her own pain, sorrow and resilience in a way that aligned with soul music’s past.

Franklin didn’t invent the genre of soul music, but she did help it reach a wider audience than ever before. Enslaved African-Americans wrote and sang soul to channel the pain and frustration of slavery and hope for liberation. “Soul is a way of life — but it is always the hard way. Its essence is ingrained in those who suffer and endure to laugh about it later,” TIME reported. The Blues genre grew out of these 19th century spirituals, and as African-Americans moved North in the early 20th century, the music began to reflect trials and tribulations of urban living—usually with jazz accompaniment. Rhythm & Blues emerged after World War II, and TIME wrote that “much if not most of what the white public knew as “rock ‘n’ roll during this period consisted of proxy performances of Negro R&B music by people like Elvis Presley and Bill Haley,” creating a “caustic resentment” among African-American musicians who felt that “white men cashed in” on their music.

Georgia native Ray Charles was critical to reclaiming the music as African-American made in the ’50s, and his brand of soul — a unique fusion of R&B, gospel, blues and jazz — was the first of its kind to be a hit in the white market. As the magazine saw it, Franklin’s popularity was further proof that soul had “arrived” and had become a permanent fixture in the pop genre, based on Americans grooving to it in the suburbs and Midwestern campuses.

Franklin was raised around this music. She was born in Memphis and grew up in Detroit—in the same neighborhood that Diana Ross, Smokey Robinson, and The Four Tops hailed from. Her father, the Rev. C. L. Franklin recorded dozens of his own sermons and made $4,000 per appearance, according to TIME’s reporting back then. Because of his name, many acclaimed gospel singers would come by her house for jam sessions, and she told TIME she wanted to become a singer after watching renowned gospel artist Clara Ward perform at her aunt’s funeral. When she started touring, she got an opportunity to audition with a New York agent, and landed a deal with Columbia Records. It wasn’t her style of music, but she found her voice with the more R&B-oriented Atlantic Records. Franklin’s first album with Atlantic, I Never Loved a Man The Way I Love You, which came out in March 1967, sold a million copies.

By June 1968, five of her singles were GOLD-certified and she had won two Grammys. Ray Charles called her “one of the greatest I’ve heard any time,” and Janis Joplin, called her “the best chick singer since Billie Holiday,” the magazine reported. To African Americans back then, soul going mainstream was even more significant because it was a sign of a growing acceptance of who they are.

But like her soul brothers and sisters who came before her, Franklin sang about a whole lot of pain. She was first traumatized at the age of 6 when her mother walked out on the family—and then her mother’s death four years later. In the 1968 cover story, TIME described how someone with an outsized personality onstage turned inward immediately when she was offstage. “I’ve been hurt—hurt bad,” she said.

Here’s how TIME described the way that heartache — and resilience — was woven into the lyrics:

She does not seem to be performing so much as bearing witness to a reality so simple and compelling that she could not possibly fake it. In her selection of songs, whether written by others or by herself, she unfailingly opts for those that frame her own view of life. “If a song’s about something I’ve experienced or that could’ve happened to me, it’s good,” she says. “But if it’s alien to me, I couldn’t lend anything to it. Because that‘s what soul is about—just living and having to get along.”

For Aretha, as for soul singers generally, “just living and having to get along” mostly involves love—seeking it, celebrating its fulfillment, and especially bemoaning its loss. Aretha pleads in Since You’ve Been Gone:

I’m cryin’! Take me back, consider me please;

If you walk in that door 1 can get up off my knees.

And in the earthy candor of the soul sound, love is inescapably, bluntly physical. In Respect, she wails:

I’m out to give you all of my money,

And all I’m askin’ in return, Honey,

Is to give me my propers when you get home . . .

Yeah, baby, whip it to me when you get home.*

“That‘s what most of the soul songs are all about,” says Negro Comedian Godfrey Cambridge. “Take Aretha’s Dr. Feelgood:

Don’t send me no doctor fillin me up with all of those pills;

Got me a man named Dr. Feelgood and, oh yeah,

That man takes care of all of my pains and my ills.

A woman works all day cooking and cleaning a house for white folks, then comes home and has to cook and clean for her man. Sex is the only thing she’s got to look forward to, to set her up to face the next day.”…

Wrestling Demons. Professionally, that is. Personally, she remains cloaked in a brooding sadness, all the more achingly impenetrable because she rarely talks about it—except when she sings. “I’m gonna make a gospel record,” she told Mahalia Jackson not long ago, “and tell Jesus I cannot bear these burdens alone.”

What one of these burdens might be came out last year when Aretha’s husband, Ted White, roughed her up in public at Atlanta’s Regency Hyatt House Hotel. It was not the first such incident. White, 37, a former dabbler in Detroit real estate and a street-corner wheeler-dealer, has come a long way since he married Aretha and took over the management of her career. Sighs Mahalia Jackson: “I don’t think she’s happy. Somebody else is making her sing the blues.” But Aretha says nothing, and others can only speculate on the significance of her singing lyrics like these:

I don’t know why I let you do these things to me;

My friends keep telling me that you ain’t no good,

But oh, they don’t know that I’d leave you if I could . . .

I ain’t never loved a man the way that I love you.

Now that Aretha can afford to be in Detroit for up to two weeks out of a month, she retreats regularly to her twelve-room, $60,000 colonial house to be with her three sons (aged nine, eight and five) and wrestles with her private demons. She sleeps till afternoon, then mopes in front of the television set, chain-smoking Kools and snacking compulsively. She does bestir herself to cook—a pastime she enjoys and is good at—and occasionally likes to get away for some fishing. But most of her socializing is confined to the small circle of girlhood friends with whom, until a couple of years ago, she spent Wednesday nights skating at the Arcadia Roller Rink.

The only other breaks in her routine are visits to her father, her brother Cecil —now assistant pastor of the New Bethel Church—or sister Carolyn, 23, who leads Aretha’s accompanying vocal trio and writes songs for her. Another sister, Erma, 29, is a pop singer living in New York City. Sometimes, with her family, she opens up enough to put on her W. C. Fields voice or do her imitation of Bela Lugosi as Count Dracula (“Goodt eeeeeevnink, Mr. Renfieldt; I’ve been expectink you!”). But Cecil says: “For the last few years Aretha is simply not Aretha. You see flashes of her, and then she’s back in her shell.” Since, as a friend puts it, “Aretha comes alive only when she’s singing,” her only real solace is at the piano, working out a new song, going over a familiar gospel tune, or loosing her feelings in a mournful blues:

Oh listen to the blues, to the blues and what they’re sayin’ . . .

Oh they tell me, they tell me that life’s just an empty scene,

Older than the oldest broken hearts, newer than the newest broken dreams.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com