These days, women in the U.S. Marines have reached all kinds of milestones. Last week, for example, the New York Times reported on how Lieutenant Marina A. Hierl, 24 — one of only two women to have passed the 13-week Marines Corps’ Infantry Officer Course at Quantico, Va. — is adapting to her new job as the first woman in the Marines to lead an infantry platoon.

This milestone comes about a century after another important one: the day Opha May Jacob Johnson, then 40, became the first woman ever sworn into the Marines Corps. Monday marks the centennial of her Aug. 13, 1918, enlistment.

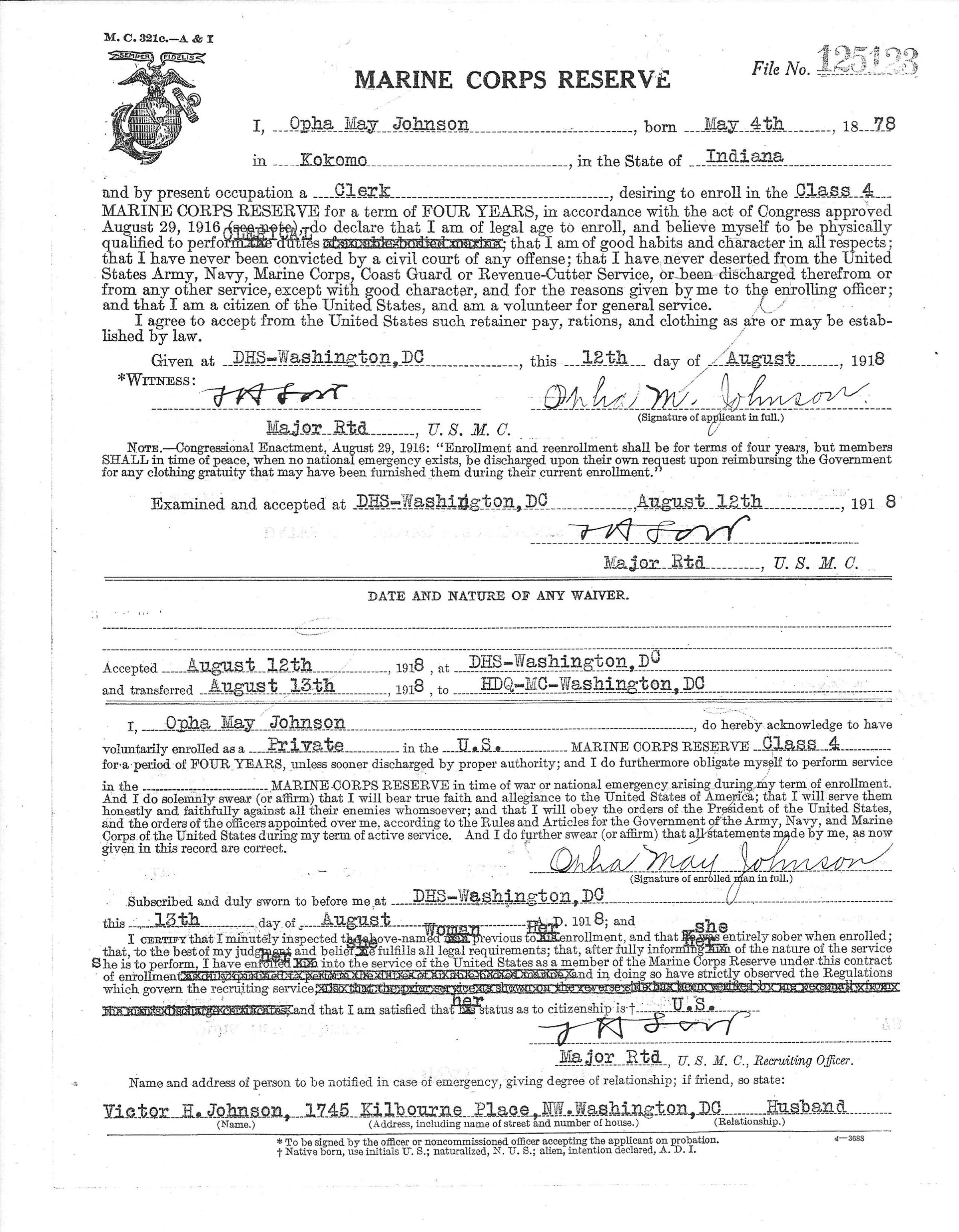

Some of the details about Johnson’s life are easy to track down: Born in Kokomo, Ind., on May 4, 1878, she was raised in D.C. and graduated second in her class from Wood’s Commercial Business College. On Dec. 20, 1898, she married a musician named Victor Hugo Johnson. Before she was in the Marines, she worked for 14 years in the civil service in the Interstate Commerce Department as Clerk to the Quartermaster General.

At some point on the job, something changed — and after that, the details get a little blurry.

Opha May Johnson is thought to have been invited to join the Marines, according to Nancy Wilt, the Women Marines Association member who started researching Johnson shortly joining the organization in 2005. “I felt there was very little history of women Marines preserved,” she says. The story also resonated with her personally. Like Johnson, she worked behind the scenes in food services and was one of two female Marine officers on a base in Millington, Tenn.

But exactly why Johnson joined and what she did on the job is still not clear, because those attempting to tell her story have not found diaries or other personal records of Johnson’s feelings. In the absence of such documents, Wilt and her colleagues have worked mostly from newspaper articles, courthouse records, performance evaluations and other documents about her in the U.S. Marine Corps archives, which suggest that her top marks prompted the invite to enlist. “She was a whiz-bang,” says Wilt of Johnson’s apparently stellar administrative skills.

On the enlistment paper she signed — showing that she passed a physical exam on Aug. 12, and enlisted on Aug. 13 — the male pronouns that were the default have been crossed out.

At the time of Johnson’s enlistment, the U.S. was in the throes of World War I, and she was one of 300 women — nicknamed “Marinettes” — to take over office jobs at Marine Corps headquarters so that the men who usually did them could be sent to France. They also supported nurses tending to victims of the 1918 influenza pandemic. By the time the Second World War, as top officers had realized how vital women were for such tasks, they had lost the cutesy nickname and gained respect. As Major General Commandant Thomas Holcomb said in the Mar. 27, 1944, issue of LIFE magazine, “They are Marines. They don’t have a nickname and they don’t need one. They get their basic training in a Marine atmosphere at a Marine post. They inherit the traditions of Marines. They are Marines.”

As for Johnson, she was promoted to Sergeant on Sept. 18 and was active-duty until February of 1919, when she is thought to have moved into a more prestigious clerical position. She stayed at Marine headquarters in D.C., and retired from government service in 1943. She died on Aug. 11, 1955, and was buried in an unmarked grave; neither she nor her brother nor her cousin left behind any children.

And perhaps partly for that reason, despite her historic tenure, even many of the women who have followed in her footsteps don’t know her name.

“I didn’t find out about her until several years after I had been in the Marine Corps. No one had taken the time to research it until Nancy did,” says Kathy Shepard, 69, of Ocala, Fla., a retired major who served for 20 years as a communications officer.

Years into her research project, Wilt was tipped off to the location of Opha May Johnson’s grave. Now, she and Shepard are part of a group raising donations from the general public and other female Marine veterans, to try to make sure that Johnson won’t be forgotten anymore.

On Aug. 29, they will unveil an obelisk marking her gravesite, in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C., the culmination of about a year of fundraising. Wilt is curating an exhibit on the lives of Johnson and her female coworkers in the Marines for the organization’s biennial convention, and hopes that someday a plaque will mark Johnson’s D.C. home.

To Wilt, the centennial of Johnson’s swearing-in couldn’t be timelier, coming during a period of new awareness of women’s roles in the workplace, including male-dominated fields like the military. That’s a lesson Wilt believes will resonate in the civilian world, too.

“The more I found out,” Wilt says, “the more I was in awe of her.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com